Osterley Park's Chinese Export lacquer armorial screen - circa 1715-20

Category

Furniture

Date

circa 1715 - 1720

Materials

Lacquer, softwood, gilding, leather, metal

Measurements

275 x 370 x 2 cm

Place of origin

Guangzhou

Order this imageCollection

Osterley Park and House, London

NT 771891.2

Summary

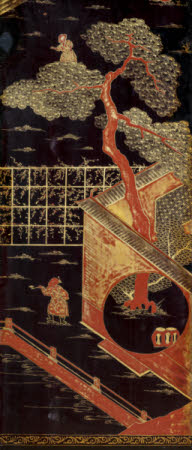

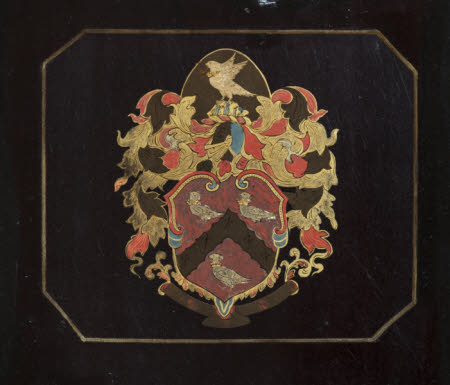

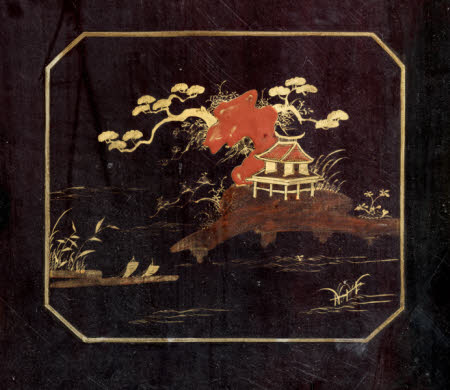

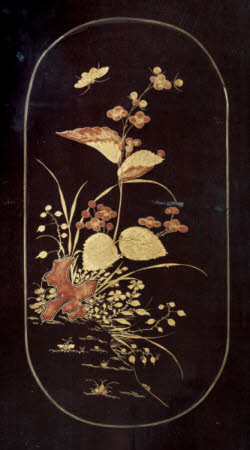

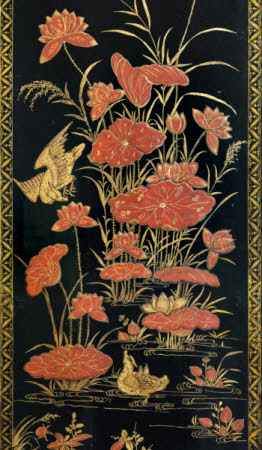

An eight-fold screen, Chinese Export, probably Guangzhou (Canton), circa 1715-20. Part of a larger group of sixteen pieces of armorial Chinese Export furniture at Osterley, comprising ten hall chairs [NT 771891.1.1-.6 owned by the National Trust; NT 773356.1-..4 the property of the Earldom of Jersey Trust]; a side table [NT 773362]; a dressing box or casket [NT 771891.3]; a single chest on later stand [NT 771891.4] and a pair of chests on later stands [NT 771891.5.1 & .5.2]. Of black lacquer upon a substrate and with a softwood core. Decorated in a palette of red, gold and silver. The front decorated with a central scene of a palace in a garden setting, with trees, decorative rocks (gongshi), pavilions, a pergola and a bridge, populated mainly by women and children engaged in various activities. This central scene all within a border of repeated splayed elongated leaves forming a chevron, between the leaves a delicate stalk or sprig of stylised foliage, all within gold lines and surrounded on the sides and the bottom by reserves with birds and flowers, landscapes, and luxury objects signifying cultivation and refinement, and along the top with reserves containing the arms and crest of Child, as granted in 1700, 'gules, a chevron engrailed ermine between three eagles close each gorged with a ducal coronet or', before a foliate mantling, beneath the crest, 'on a Rock proper an eagle rising argent holding in the beak an adder proper', on a torse. The back decorated with bird-and-flower scenery, with one hanging-scroll-like picture on each of the six central panels of the screen, showing flowering and fruiting plants and trees including peony, Buddha’s hand citron, lotus and cherry, rising from grassy or watery foregrounds, interspersed with decorative rocks ('gongshi') and with birds and insects including egrets, butterflies, ducks, hummingbirds, magpies, chickens and crested mynas. The central hanging-scroll-like images surrounded on all four sides by reserves with birds and flowers, landscapes, and luxury objects signifying cultivation and refinement. The screen once with simple block feet, now lacking. The hinges probably replaced and now beneath edging strips of leather. The decoration re-touched in places.

Full description

This screen, decorated with the Child coat of arms, is one of only a handful of armorial screens to survive in England. Other examples include: an eight-fold screen bearing the arms of Hobart impaling Howard, at Marble Hill House [EH 88029493]; another, of six folds, with the arms of the Dukes of Hamilton quartering the Earls of Arran, at Petworth [NT 485395]; and a twelve-panel screen bearing the arms of John Eccleston (1678-1735), who, like the Child family, was heavily involved in the East India Company [in the Peabody Essex Museum, Massachusetts, E84093]. Three others are known from surviving documentation. First, two six panel screens were listed in an inventory taken at Cannons in 1725, the house of James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos (1674–1744); another – ‘of 8 Leaves and 8 foot high’ – was ordered by the Tower family of Huntsmoor Park.[1] The families who owned these screens were either aristocrats or men, like John Eccleston and Christopher Tower (d. 1728), who were closely associated with the East India Company. Lacquered furniture like this was exclusively the preserve of early 18th century England’s richest men, the millionaires who amassed spectacular fortunes from trade, speculation and investment in emerging markets, and the aristocrats who knew them, or were their clients. Made in Guangzhou (Canton) in China, specifically for export, this furniture was only available via the East India Company, the chartered British concern with a monopoly on trade with China. English families commissioned a range of objects bearing their arms [2] – porcelain, textiles and different types of furniture – but remarkably, Osterley is the only place where such a large and diverse group has survived together, in the house of the family for which it was made. That sixteen pieces of armorial furniture have remained together, protected in law as heirlooms, is a measure of their rarity and value, and of the esteem in which they were held.[3] Lacquer is a decorative technique which was perfected by Japanese and Chinese artists, involving the building up of layers – on a timber or other substrate – of the sap of the Rhus vernicflua tree. The lustrous surface which results provides the perfect background for decoration in gilt and colours. By 1720, furniture like this was being made in Guangzhou and was largely the preserve of the private trade in which East India Company captains, investors and directors were authorised to engage, alongside carrying out the official trade of the Company. Captains, crew members and overseers called ‘supercargoes’ were allowed to reserve a portion of the ships’ tonnage for their own goods, or goods which they had been commissioned to buy. Registers of private cargo leaving Guangzhou on ships between 1721 and 1740 show that in 1720-1 captain John Hill imported two lacquer screens; in 1723-4, supercargo Richard Nicholson imported two more; in 1728-9, no fewer than sixteen screens being privately traded were listed amongst the cargo of ships bound for England. In addition, that year supercargo Henry Talbot shipped ‘3 cases of screens’. The latter is a reference to the fact that lacquer was brought back to England in boards or sheets, flat-packed in cases, only assembled into three dimensional furniture when it arrived in England.[4] Families who commissioned goods from China bearing a coat of arms had first to send a tracing of that coat to China. This was not the only means by which the influence of English consumers was brought to bear on the form and decoration of export wares, particularly where furniture was concerned. As early as 1702, when the London Company of ‘Joyners’ petitioned for the importation of Asian lacquer – because it threatened their own livelihoods – to cease, their complaint was not that Chinese furniture was being brought into England, but that Chinese furniture made after English models was being brought into England. Thus, they wrote, ‘several merchants…have procured to be made in London…and sent over to the East Indies, Patterns and Models of all sorts of Cabinet Goods.’[5] This exchange produced furniture which was a complex bicultural amalgam. The furniture followed English fashions and forms but was made with Chinese joinery and decorated with Chinese lacquer. To complicate this picture still further, the timber used to make furniture in Guangzhou was often imported into China from other parts of Asia by East India Company ships.[6] Of all of the types furniture imported into England from Guangzhou, screens were the most typically ‘Asian’ in form, exhibiting little English influence other than in the number of folds that English buyers chose.[7] Folding screens were in use in England from the late 16th or early 17th centuries – the 1605 inventory of Hengrave Hall in Suffolk lists ‘one great foulding skrene of seaven foulds’[8] – but how exactly they were used it is more difficult to ascertain. In Asia, screens were traditionally placed just inside the doorway into a room, to literally screen the view of anyone looking into it. This practice is also said to have ensured – by forcing a person to enter a room sideways – a decorous entrance. Screens were used in European outposts in Asia in the same way. A carved screen procured by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was placed inside the entrance to their Council Room in Batavia.[9] They may have been used in this way in England, or to exclude draughts, but whilst inventories show that they were used in a variety of different rooms in English houses they are not, of course, detailed enough to specify where in a particular room they were located. The 1st Duke of Brydges installed one of his six-fold screens in the Library at Cannons, whilst the other was in the State Chamber and Closet in his house in St James’ Square.[10] In the inventory taken at Erddig in 1726, a ‘large Leather Screen’ was listed amongst the contents of the Saloon.[11] There is no convincing reference to the Child’s armorial screen in the 1782 Osterley inventory. The Dressing Room associated with the Yellow Damask Bedchamber in the house’s South Front was furnished with ‘An India folding screen with nice figures’ whilst ‘An eight leaved India Paper fire screen’ stood in the Chintz Bedchamber. The latter – being of eight folds – is the nearest match, although it seems improbable that the takers of the inventory would describe it as made of ‘paper’. In addition, when listing the lacquered hall chairs, they added that they bore ‘the family Arms’ but make no mention of ‘arms’ when describing either of these folding screens.[12] When exactly this screen was commissioned, and by whom, it is difficult to say precisely. It is possible, of course, that the surviving armorial furniture at Osterley was the product of several different commissions, as the pieces are of varying quality, and their decoration is clearly not the product of the same hand. The chests and chairs – with decoration confined to the arms and a simple border of leafy chevrons and sprigs – are more restrained, for instance, than this screen and the dressing box or casket, which are highly decorated with landscape scenes and figures. Francis Child I (d. 1713) and his three sons were all heavily involved in the East India Company. Francis I served as a Director and sat on various committees. His eldest son, Robert Child (d. 1721), followed suit and was elected Chairman in 1715, the same year he was knighted by George I. Francis Child II (1684-1740) and Samuel Child (1693-1752) both also served as Directors, and Samuel held a large number of EIC stocks, and co-owned the EIC chartered ship the Northampton.[13] It is tempting to think that Robert Child commissioned this armorial furniture to commemorate the dual honours of his knighthood and his Chairmanship of the East India Company. The kind of scenery depicted on the front of the screen is probably inspired by idealised images of court life in the Han dynasty (202BC-220AD), revived and popularised by the Song dynasty painter Qiu Ying (c.1494-c.1552), whose work in turn influenced 17th-century woodblock illustrations. [14] The motifs and scenery on this screen have a long pedigree in Chinese art, with the landscapes embodying the Daoist-inspired conception of the universe as a dynamic harmony of opposites and the birds and flowers having numerous symbolic and auspicious connotations. [15] Megan Wheeler and Emile de Bruijn, October 2019 [1] See Patricia Ferguson, 'Chinese Armorial Wares for James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos: Self-Fashioning or Artifice?', Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol. 82, 2017-18, pp.37-47, pp. 43-45. [2] See, for instance, the will of Martha Page (d. 1729), the widow of Sir Gregory Page (d. 1720), which records a ‘square Japan table / with the coat of arms’ as well as ‘1 paire small [mugges] with armes’ (see National Archives, PROB 11/628/300). Two sets of Chinese armorial chairs (not mentioned in Martha Page’s will) also survive bearing the family’s arms. The first set, very similar to the lacquered chairs at Osterley, dates from circa 1714-20 (see A. Bowett, Early Georgian Furniture 1715-40 (2009), pp. 154-5 and Fig. 4:16. The second set, of rosewood inlaid with mother-of-pearl are in the Soane Museum (see H. Dorey, ‘A Catalogue of Furniture in Sir John Soane’s Museum’ in Furniture History XLIV (2008), 47-50.) Many more examples of armorial porcelain than furniture are known. [3] A seventeenth piece, also bearing the arms of Child, and probably a pair to the single small chest now in the Gallery at Osterley (NT 771891.4) was sold Sotheby’s, 3 July 1997, Lot 16. The existence of this chest makes it possible that the set was once larger. [4] Kyoungjin Bae, Joints of Utility, Crafts of Knowledge: The Material Culture of the Sino-British Furniture Trade during the Long Eighteenth Century (PhD Thesis, Columbia University, 2016), pp. 50-3 and 56-7. [5] ibid., pp. 23-4. [6] ibid., pp. 26-46. [7] Twelve-fold screens were common in Asia but surviving screens (the Page screen aside) and documentary references suggest that, in England, smaller screens of six- or eight-fold screens were most common. This screen at Osterley was probably intended as a twelve-fold screen, since the pattern or decoration between the first and second folds, and the seventh and eighth folds, does not line up, or continue logically. See Ferguson, 'Chinese Armorial Wares for James Brydges' (TOCS 2017-18), p. 43. [8] R. Edwards, The Shorter Dictionary of English Furniture (1964), pp. 433-4. [9] Asia in Amsterdam:The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age, edited by Karina H. Corrigan, Jan van Campen, Femke Diercks and Janet C. Blyberg (2015), pp. 43-4. [10] Ferguson, 'Chinese Armorial Wares for James Brydges' (TOCS 2017-18), p. 43. [11] Flintshire Record Office, MS Hawarden DE/280, Inventory for Wales, 5 August 1726. [12] M. Tomlin, ‘The 1782 Inventory of Osterley Park’ in Furniture History XXII (1986), p. 113. [13] Y. Sharma & P. Davies, ‘A jaghire without a crime’: The East India Company and the Indian Ocean material world at Osterley, 1700-1800’ in East India Company at Home, 1757-1857, eds. M. Finn & K. Smith (2018), p. 91. [14] See He, Feng, ‘Ming Dramas as Sources for the Dancing Scene on Coromandel Lacquer Screens and Kangxi Porcelains’, in The oriental ceramic Society Newsletter, no. 26 (May 2018), pp. 3–6; and He, Feng, ‘The Global Lives of a Female Dancer: Transcultural Identities of a Chinese Painting Motif’, in Aziatische Kunst, vol. 47, no. 2 (July 2017), pp. 5–12. [15] See McCausland, Shane, ‘Categories of Paintings in China: Genres and Subjects’, in Zhang Hongxing (ed.), Masterpieces of Chinese Painting 700–1900, London, V&A Publishing, 2013, p. 41–52; Rawson, Jessica, ’Ornament as System: Chinese Bird-and-Flower Design’, in The Burlington Magazine, vol. 148, no. 1239 (June 2006), pp. 380–9; and Bjaaland Welch, Patricia, Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery, Tokyo, Rutland and Singapore, Tuttle, 2008.

Provenance

A Child Family Heirloom. By descent, until given by George Francis Child-Villiers, 9th Earl of Jersey (1910-1998) in 1993.

References

Ferguson, P (2017), 'Chinese Armorial Wares for James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos: Self-fashioning or Artifice?' (Lecture given by Patricia E. Ferguson, 10 October 2017), 5, 7-9 National Archives, PROB 11/628/300 Bowett 2009, Early Georgian Furniture 1715 - 1740 (2009), pp.154-5 and Fig. 4:16 Dorey, H (2008): 'A Catalogue of Furniture in Sir John Soane's Museum' in Furniture History XLIV (2008), 47-50 Bae, K (2016), Joints of Utility, Crafts of Knowledge: The Material Culture of the Sino-British Furniture Trade during the Long Eighteenth Century (PhD Thesis, Columbia University, 2016), pp.23-4, 26-46, 50-3 and 56-7 Edwards, Ralph, 1894-1977 shorter dictionary of English furniture : 1964., pp.433-4 Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age eds. Karina H. Corrigan, Jan van Campen, Femke Diercks and Janet C. Blyerg (2015), pp.43-4 Flintshire Record Office, D/E/280 Tomlin, 1986: Maurice Tomlin. “The 1782 inventory of Osterley Park.” Furniture History 22 (1986): pp.107-134., 113 Sharma, Y & Davies, P. (2018), 'A jaghire without a crime': The East India Company and the Indian Ocean material world at Osterley, 1700=1800', in East India Company at Home, 1757-1857, eds. M. Finn & K. Smith (2018), 91 He, Feng (2018), 'Ming Dramas as Sources for the Dancing Scene on Coromandel Lacquer Screens and Kangxi Porcelains', in The Oriental Ceramic Society Newsletter, No. 26 (May, 2018), 3-6 He, Feng (2017), 'The Global Lives of a Female Dancer: Transcultural Identities of a Chinese Painting Motif', in Aziatische Kunst, Vol. 47, No. 2 (July, 2017), 5-12 McCausland, Shane (2013), 'Categories of Paintings in China: Genres and Subjects', in Zhang Hongxing (ed.), Masterpieces of Chinese Painting 700-1900 (V&A Publishing, London, 2013), 41-52 Rawson, 2006: Jessica Rawson. “Ornament as system: Chinese bird-and-flower design.” Burlington Magazine 148.[Nostell p.1239] 2006: 380-9. Bjaaland Welch 2008: Patricia Bjaaland Welch, Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery, Tokyo, Rutland (Vermont) and Singapore, 2008