Mazarine

Frederick Kandler (d.1778)

Category

Silver

Date

1751 - 1752

Materials

Silver

Measurements

43.8 cm (Width) x 27.6 cm (Depth)

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852080.4

Summary

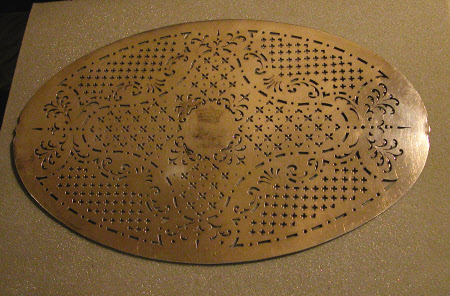

Mazarine, sterling silver, by Frederick Kandler, London, 1751/2. One of two, associated with dishes of the same date (NT 852080.1 & 3) The mazarine is formed of a flat oval sheet of silver pierced with a symmetrical pattern of foliate scrolls and diaperwork. Heraldry: The centre of the mazarine is engraved with the Hervey crest beneath an earl’s coronet.

Full description

Pierced strainers for fish emerged as a feature of the Georgian dinner service around the year 1730 and two names coexisted for them, ‘fish plate’ and ‘mazarine’. George Wickes exclusively used the former whereas the Jewel Office favoured the latter. In 1708 mazarines were defined in John Kersey’s Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum as ‘little Dishes to be set in the Middle of a larger Dish, for the setting out of Ragoos, or Fricassies’ [1] and that is clearly what the Earl (later Duke) of Marlborough was receiving from the Jewel Office in 1702. Amongst his plate as Captain General of the Forces in Holland he had thirty-two gilt ‘mazarines’ which were listed after the large dishes upon which they would presumably have been placed.[2] No more of this type are mentioned after 1705, when sixteen formed part of Lord Raby’s ambassadorial plate,[3] and they can never have been common, but the fact that they rested upon another dish has been plausibly suggested by Susan Hare as the reason for the term subsequently being applied to fish strainers.[4] That is what must have been meant when in 1728 the 4th Earl of Chesterfield received ‘Three Mazareens’ weighing 58 oz 6dwt as part of his allowance on going to the States General as ambassador [5] and those granted to the 2nd Lord Tyrawley and the 4th Earl of Holderness in 1744 are specified as being ‘pierced’.[6] Large numbers of fish mazarines were produced in the eighteenth century, every significant household having at least one, yet hardly any survive today and even fewer are on public display. Ickworth is thus particularly fortunate to have the full complement of two mazarines with their associated dishes (NT 852080.1 &3). Amongst the handful of earlier examples still in existence are four by Paul de Lamerie; a pair of 1743 from his extensive dinner service for the 7th Earl of Thanet and individuals of 1744 and 1745, the latter from the plate of the Parkers, Earls of Morley.[7] James Rothwell, Decorative Arts Curator February 2021 [Adapted from James Rothwell, Silver for Entertaining: The Ickworth Collection, London 2017, cat. 33, pp. 112-13.] Notes: [1] John Kersey, Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, 1708, under the entry for ‘Mazarines’ (not paginated). [2] The National Archives, LC 9/44, Jewel Office Delivery Book 1698–1732, f. 74. Substantial quantities of this sort of mazarine had been recorded in the royal scullery in 1698 and William III took 56 with him to Holland in 1700, in three different sizes, see ff. 11 and 47. [3] Ibid., f. 112. [4] Susan Hare (ed.), Paul de Lamerie, at the Sign of the Golden Ball, 1990, p. 167. [5] Jewel Office Deliver Book 1698–1732 (see note 2), f. 297. [6] The National Archives, LC 9/45, Jewel Office Delivery Book 1732–98, f. 92 [7] Sold Sotheby’s 22 November 1984 (1743) and 24 April 1969, lot 242 (1744) and Christie’s New York, 22 April 1993, lot 58 (1745).

Provenance

George Hervey, 2nd Earl of Bristol (1721-75); by descent to the 4th Marquess of Bristol (1863-1951); accepted by the Treasury in lieu of death duties in 1956 and transferred to the National Trust.

Credit line

Ickworth, the Bristol Collection (National Trust)

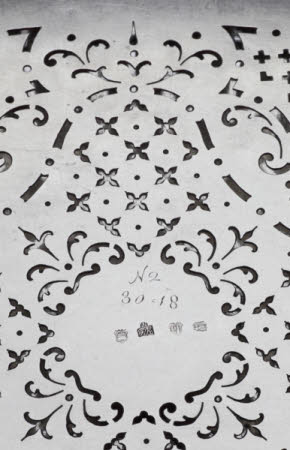

Marks and inscriptions

Underside: Hallmarks: maker’s mark ‘FK’ in italics beneath a fleur-de-lis (Arthur Grimwade, London Goldsmiths 1697-1837, 1990, no. 691), date letter ‘q’, leopard’s head and lion passant. Underside: Scratchweight: ‘N2 [/] 30=18’ .

Makers and roles

Frederick Kandler (d.1778), goldsmith