Pair of large oval dishes with mazarines and pair of oval tureen dishes

Frederick Kandler and Turin

Category

Silver

Date

1751 - circa 1756

Materials

Silver

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852080

Summary

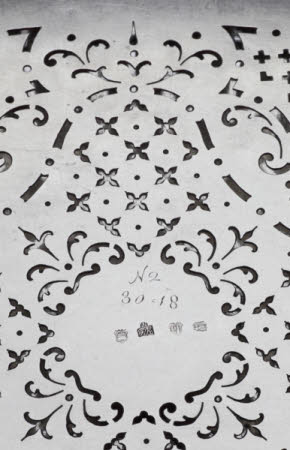

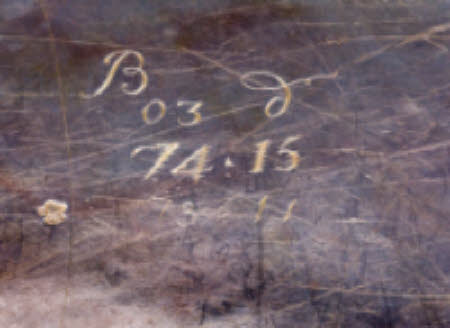

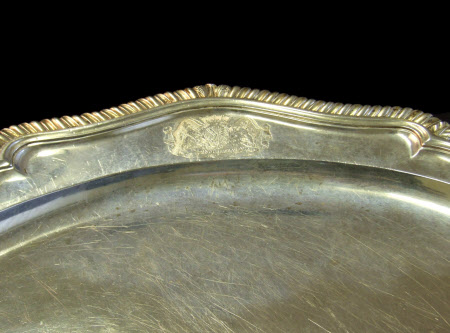

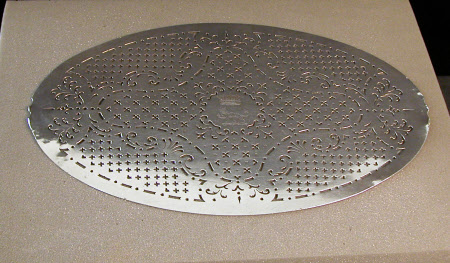

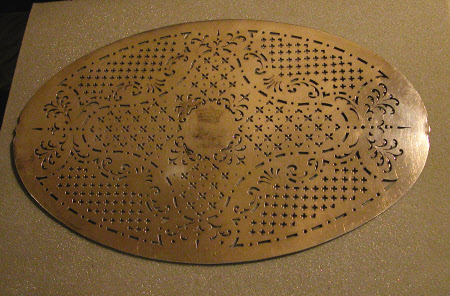

Pair of large oval dishes and associated pair of mazarines, sterling silver, by Frederick Kandler, London, 1751/2; pair of oval tureen dishes, silver, Turin, c.1756. The dishes and tureen dishes are raised and have flat oval wells and broad rims with shaped borders applied with cast and chased gadrooning. Two large cast and chased shells are applied to each as handles. The mazarines are formed of a flat oval sheet of silver pierced with a symmetrical pattern of foliate scrolls and diaperwork. Heraldry: Engraved on the rim of the dishes and tureen dishes are the quartered shield, supporters and motto of the 2nd Earl of Bristol in an ermine mantling and beneath an earl’s coronet. The engraving on the tureen dishes is Italian (see NT 852078). The centre of each mazarine is engraved with the Hervey crest beneath an earl’s coronet. Hallmarks: The large oval dishes are fully marked on the underside of the rim and the mazarines on their undersides with maker’s mark ‘FK’ in italics beneath a fleur-de-lis (Arthur Grimwade, London Goldsmiths 1697-1837, 1990, no. 691), date letter ‘q’, leopard’s head and lion passant. The underside of each oval tureen dish is struck with the assay mark of Bartolomeo Pagliani, the Savoy cross in a shield flanked by ‘B P’ with a closed crown above (see Gianfranco Fina & Luca Mana, Argenti Sabauda del XVIII Secolo, 2012, p. 248). Scratchweights: large oval dishes - ‘N1 [/] 92=15’ and ‘N2 [/] 93=10’; mazarines - ‘N1 [/] 28=11’ and ‘N2 [/] 30=18’; oval tureen dishes - ‘A oz d [/] 74 ∆ 18 [/] 73 = 15’ and ‘B oz d [/] 74 ∆ 15 [/] 73 = 11’ Measurements: Large oval dishes - H: 5.1 cm; W: 59.4 cm; D: 36.5 cm. Mazarines - W: 43.5 cm; D: 27.3 cm. Oval tureen dishes - H: 4.8 cm; W: 57.5 cm; D: 36.5 cm.

Full description

LARGE OVAL DISHES For service à la française, which held sway until the mid nineteenth century, dishes were supplied in gradated sizes and arranged on the table for diners to help themselves to the food thereon. In the decades around 1700 the dishes were generally of circular shape as is made abundantly clear by surviving examples [1] and also by the table layouts given by François Massialot in his Nouveau cuisinier royal et bourgeois, first published in 1691 and translated into English as The court and country cook in 1702.[2] Oval dishes were not unknown [3] but they seem to have been rare and it was only in the 1730s that significant numbers began to appear in England.[4] They were shown in the plates of Vincent La Chapelle’s highly influential The modern cook of 1733, some with shaped borders,[5] and by 1740 they were becoming commonplace, often augmented by gadrooning as seen on the Ickworth examples. An exceptionally early group of oval shaped dishes, with elaborate Régence decoration, is that of 1731 made by Charles Kandler for the 9th Duke of Norfolk.[6] They exhibit diminutive cast shells protruding at either end, presumably there in part to assist with lifting the dishes as were the flanges of 1720s epergne dishes (see cat. 13). It could thus have been from the Kandler workshop that the idea emanated of more prominent shell handles as seen on the Ickworth dishes, though they were more probably directly inspired by Continental ecuelles [7] and their English equivalents, porringers. A good example of the latter with prominent shell handles is a pair by David Willaume marked for 1721 at Winterthur.[8] The earliest dishes extant of the Ickworth type are all of 1741, a large batch (some circular) by Paul de Lamerie and a pair by George Wickes.[9] The shell handles on these are very similar but not identical, that employed by Wickes being more symmetrically arranged and having lateral fronds projecting beyond the border plus trios of pearl-like balls. It is the Wickes model that was used by Edward Wakelin in 1748 for Admiral Byng’s dinner service [10] and by Kandler from 1751 onwards for all of Lord Bristol’s larger dishes. Thus the two most prominent retailers of the mid-century were either sourcing from the same outworkers or sharing moulds, and a third option might even be that Kandler had simply taken a cast from a Wickes dish. The feature was to prove a resilient one, being further copied in the early nineteenth century by Rundell, Bridge and Rundell for the dinner service provided to William IV,[11] and in that case the inspiration is very likely to have been the Bristol plate (see NT 852103) which Rundells had had access to. It is evident from wear and tear that the Ickworth dishes were not exclusively used with the fish plates or mazarines with which they were supplied (NT 852080.2 & 4) but the need to ensure that they fitted when thus employed is probably why, unlike the other eight oval dishes of c.1751 (NT 852095.1-2 & 7-8 and 852096), these ones were new-made. As the largest of all the sizes of dish they would have contained the principal focus of the first and second courses, other than the soups. When being used for fish they might, for instance, have contained a turbot and a salmon to replace the two principal soup tureens as part of the first course. For the second they could take the same place, Vincent La Chapelle suggesting Savoy Cake and ‘a Cake of mille Feuilles’. Alternatively, if used for meat, they might contain a quarter of veal or a roasted ham.[12] MAZARINES Pierced strainers for fish emerged as a feature of the Georgian dinner service around the year 1730 and two names coexisted for them, ‘fish plate’ and ‘mazarine’. George Wickes exclusively used the former whereas the Jewel Office favoured the latter. In 1708 mazarines were defined in John Kersey’s Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum as ‘little Dishes to be set in the Middle of a larger Dish, for the setting out of Ragoos, or Fricassies’ [13] and that is clearly what the Earl (later Duke) of Marlborough was receiving from the Jewel Office in 1702. Amongst his plate as Captain General of the Forces in Holland he had thirty-two gilt ‘mazarines’ which were listed after the large dishes upon which they would presumably have been placed.[14] No more of this type are mentioned after 1705, when sixteen formed part of Lord Raby’s ambassadorial plate,[15] and they can never have been common, but the fact that they rested upon another dish has been plausibly suggested by Susan Hare as the reason for the term subsequently being applied to fish strainers.[16] That is what must have been meant when in 1728 the 4th Earl of Chesterfield received ‘Three Mazareens’ weighing 58 oz 6dwt as part of his allowance on going to the States General as ambassador [17] and those granted to the 2nd Lord Tyrawley and the 4th Earl of Holderness in 1744 are specified as being ‘pierced’.[18] Large numbers of fish mazarines were produced in the eighteenth century, every significant household having at least one, yet hardly any survive today and even fewer are on public display. Ickworth is thus particularly fortunate to have the full complement of two mazarines with their associated dishes (NT 852080.1 &3). Amongst the handful of earlier examples still in existence are four by Paul de Lamerie; a pair of 1743 from his extensive dinner service for the 7th Earl of Thanet and individuals of 1744 and 1745, the latter from the plate of the Parkers, Earls of Morley.[19] OVAL TUREEN DISHES Not only did George Hervey, 1st Earl of Bristol discover that he needed additional tureens when he came to Turin (see NT 852128 & 852105) but he must also have realised that he could not present them or their oval equivalents at table without dishes beneath them as stands. These were not uncommon in Britain and had been regularly supplied by the Jewel Office and George Wickes since the 1720s but they were by no means universal in use, even in the most elevated and fashionable of households. Thus, although the future 1st Duke of Leinster was in advance of his times in having matching dishes for his tureens in 1747, the Marquis of Granby did not have them for the ‘Fine Tureens’ of his dinner service of 1750.[20] French examples were by this time often ornamented specifically to suit the tureens that were to stand on them, as that made by Étienne-Jacques Marcq in 1755 now in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.[21] This meant that they had no other practical use which, combined with the large amount of workmanship and their consequent cost, probably militated against Lord Bristol commissioning anything on such lines. His tureen dishes therefore matched exactly the dishes he had already commissioned from Frederick Kandler (NT 852080.1 & 3) and as a consequence their intended primary purpose was soon forgotten. Tureen stands never became universal in Britain and the 2nd Earl’s successors had ceased to record these ones as such by 1811, when the future 1st Marquess’s plate was listed.[22] Fortunately, however, the round dishes were noted as being for the Turin tureens on the death of the 4th Marquess [23] and an inspection of the oval pair revealed they had been marked by the feet of the Kandler tureens. James Rothwell, Decorative Arts Curator February 2021 [Adapted from James Rothwell, Silver for Entertaining: The Ickworth Collection, London 2017, cat. 32, 33 & 55, pp. 111-13 & 140-41.] Notes: [1] See for instance Sir Rowland Winn, 3rd Bt’s dinner service of 1716 by David Willaume I, with three sizes of dish, sold at Christie’s, 3 November 1999, lots 86–9. [2] François Massialot, The court and country cook, 1702, illustrative plates, not paginated. See particularly ‘The Model of a Table for fourteen of fifteen Persons’ which shows three gradations of circular dishes plus plates in use for service as well. [3] See for instance that of 1684 illustrated in Michael Clayton, The Collector’s Dictionary of the Silver and Gold of Great Britain and the United States, 1971, p. 111, no. 235. The Earl of Strafford received four oval dishes in 1713/4 as part of his ambassadorial allocation of plate on going to Utrecht; see The National Archives, LC 9/44, Jewel Office Delivery Book 1698–1732, f. 171. [4] Initially these were primarily oval wells within a polygonal surround, or a rectangle with lobed ends. See Clayton 1971 (see note 3), p. 111, no. 234 for a polygonal set by David Willaume I, 1725 and James Lomax and James Rothwell, Country House Silver from Dunham Massey, 2006, cat. 25, pp. 73-5 for rectangular lobed examples by Peter Archambo 1731. [5] Vincent La Chapelle, The modern cook, 1733, unpaginated plates showing table layouts at the beginning of volume 1. [6] Sotheby’s New York, 22 October 2002, lot 589. [7] For an example of 1735 by Antoine Plot of Paris see Faith Dennis, Three Centuries of French Domestic Silver, 1960, p. 188, fig. 280. [8] Donald L. Fennimore and Patricia A. Halfpenny, Campbell Collection of Soup Tureens at Winterthur, 2000, cat. 9, pp. 24-5. [9] For the de Lamerie dishes see Christie’s, 19 June 1957, lot 24, and 29 June 1977, lot 88, and Sotheby’s 24 March 1960, lot 6 plus a gradated set of seven in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, acc. nos. 58.7.23-9. The Wickes pair, which had been supplied to Sir Henry Harpur, 5th Bt, was sold at Christie’s New York, 28 October 1986, lot 34. See also Elaine Barr, George Wickes, 1980, p. 23, figs 6a-d. [10] This service was delivered in March 1749; National Art Library, Garrard Ledgers, VAM 3 1747–50, f. 83. Four dishes from it by Edward Wakelin, 1748 were sold at Sotheby’s New York, 23 October 2006, lots 287-8. [11] A dish with shell handles from this service was sold at Christie’s, 10 June 2010, lot 483. [12] Vincent La Chapelle, The modern cook, 1736, plate VII. [13] John Kersey, Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, 1708, under the entry for ‘Mazarines’ (not paginated). [14] The National Archives, LC 9/44, Jewel Office Delivery Book 1698–1732, f. 74. Substantial quantities of this sort of mazarine had been recorded in the royal scullery in 1698 and William III took 56 with him to Holland in 1700, in three different sizes, see ff. 11 and 47. [15] Ibid., f. 112. [16] Susan Hare (ed.), Paul de Lamerie, at the Sign of the Golden Ball, 1990, p. 167. [17] Jewel Office Deliver Book 1698–1732 (see note 14), f. 297. [18] The National Archives, LC 9/45, Jewel Office Delivery Book 1732–98, f. 92 [19] Sold Sotheby’s 22 November 1984 (1743) and 24 April 1969, lot 242 (1744) and Christie’s New York, 22 April 1993, lot 58 (1745). [20] National Art Library, Garrard Ledgers, VAM 3 1747–50, ff. 1 and 166. [21] Claude Frégnac (ed.), Les grands orfèvres de Louis XVIII à Charles X, 1965, p. 160, ill. [22] Suffolk Record Office, 941/75/1, list of plate belonging to the 5th Earl and 1st Marquess of Bristol, 1811-40. [23] Suffolk Record Office, HA 507/9/21, list of silver offered in lieu of death duties following the death of the 4th Marquess of Bristol, c.1951, p. 9.

Provenance

George Hervey, 2nd Earl of Bristol (1721-75); by descent to the 4th Marquess of Bristol (1863-1951); accepted by the Treasury in lieu of death duties in 1956 and transferred to the National Trust.

Credit line

Ickworth, the Bristol Collection (National Trust)

Makers and roles

Frederick Kandler and Turin, goldsmith