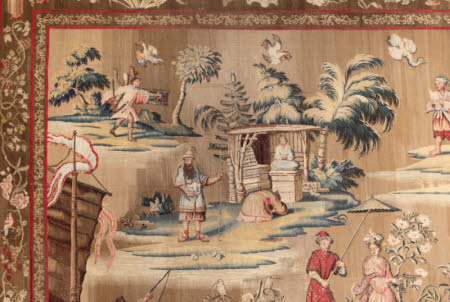

Tapestry after the Indian Manner

John Vanderbank the elder (fl. 1682 - d. 1717)

Category

Tapestries

Date

circa 1691 - circa 1692

Materials

Tapestry, wool and silk, 9 warps per cm

Measurements

3.37 m (H); 4.21 m (W)

Place of origin

Soho

Order this imageCollection

Belton House, Lincolnshire

NT 436999.1

Summary

Tapestry, wool and silk, 9 warps per cm, one of two Tapestries after the Indian Manner, John Vanderbank, London, c. 1691-2. A tapestry with a number of small, colourful figure groups arranged on a tobacco-coloured ground. These include women walking in a landscape with attendants carrying parasols near the centre, fishermen on the left hand side, the veneration of a statue of Buddha at top left, boatmen carrying vegetables at lower right, a nurse with a child pushing a bird on a cart at centre right, and a mule carrying passengers in the upper centre. The tapestry has borders with vases and birds on a brown ground, with two narrow bands of decoration at the inner and outer edges. Blue galloons are visible on all four sides, and the signature IOHN VANDREBANC FECIT appears on the lower galloon.

Full description

As Edith Standen has noted (Standen 1980, pp. 134-138), the majority of the figures in this tapestry derive from the illustrations to the English edition of Arnold Montanus's 'Atlas Japannensis', first published in Amsterdam in 1669 and published in English the following year by John Ogilby. For example, the fishermen on the left hand side are taken from an illustration of the modes of fishing seen at a town called Duvos (Ogilby 1670, p. 74), and the woman near the centre being followed by a servant carrying a parasol is taken from an illustration of the costumes of the inhabitants of Naugasaque (Nagasaki) (Ogilby 1670. p. 77). The two 'Tapestries after the Indian Manner’ at Belton House, commissioned in 1691 and signed by John Vanderbank, are the earliest surviving example of one of the most popular designs in the history of English tapestry. Each panel is made up of a series of lively and exotic small figure groups arranged on a plain brown ground. The overall effect is clearly intended to imitate the Japanese and Chinese lacquer panels that were imported into Europe in increasingly large quantities in the seventeenth century. Such panels were used as screens or in pieces of furniture, or on occasion set into the panelling of walls, as the Belton tapestries have been since the 1690s. With the increase in trade between Europe and the far East during the seventeenth century, largely through the channels of the Dutch and English East India companies, came a new taste for imported furniture and luxury goods including oriental porcelain, lacquer and textiles (see for example Impey 1977; Jarry 1981). Western artists and craftsmen also began imitating the forms and decoration of imported wares. The 1698 inventory of Belton House, remodelled by Sir John Brownlow in the 1680s and 1690s, lists a Chinese cabinet assembled from imported lacquer panels, and a collection of Chinese porcelain alongside Vanderbank’s tapestries (Belton 1983). The taste for such goods was eclectic, and the terms 'Chinese', 'Japanese' and 'Indian' were used fairly indiscriminately in the late seventeenth century to describe images and objects of oriental inspiration. Despite the design sources deriving from Japanese sources, Vanderbank’s tapestries were referred to at the time as ‘after the Indian Manner’. The term ‘Chinoiserie’, used today to describe goods made in this broad style, only became widespread in the late nineteenth century (Mitchell 2007, p. 11). The two tapestries are signed 'IOHN VANDREBANC FECIT' for John Vanderbank (fl. 1682 – d. 1717), a weaver of Flemish origin who had worked in Paris, and was appointed Yeoman Arrasworker to William III and Queen Mary in 1689, a year after their accession to the British throne. Vanderbank's 'Indian Manner' tapestries were first recorded in 1690, when a set of four was commissioned for Queen Mary's apartments at Kensington Palace. The tapestries were the first royal commission from Vanderbank (Standen 1980, p. 119; Thomson 1914, p. 143). Queen Mary's tapestries do not survive, but there is evidence to suggest that the pair at Belton reflect their appearance very closely. The tapestries were commissioned by Sir John Brownlow from Vanderbank in 1691, the year the royal set was delivered. Vanderbank's contract with Brownlow, dated 12 August 1691, survives among the Belton papers, and specifies that the tapestries were to be identical to those at Kensington: "That he the said John Vanderbank shall make two pieces of Tapestry hangings according to the dimensions to be given by the said Sr John Brownlow and the said hangings are to be of Indian figures according to ye pattern of the Queens wch are at Kensington and to be finished as well in every kind or else the said Sr John Brownlowe shall not be obliged to have theme ... but if the hangings aforesaid be finished and made according to the said pattern the said Sr John Brownlowe is to pay unto the said John Vanderbank fifty shillings per dutch ell Square to be paid as followeth that is to saye fifteen pounds monthly for six months and the rest when they shall be delivered wch shall bee within the space of seven months from the date hereof..." (Belton 1983). Vanderbank's 'Chinoiserie' or 'Indian manner' tapestry design was to prove immensely popular, and there are numerous records of commissions from Vanderbank for these tapestries, right up until the 1720s. As well as the model used for Queen Mary and at Belton, Vanderbank also produced a second, related design with slightly smaller and less elaborate figures, which would therefore have been cheaper to produce. Whereas most of the figures in the Belton tapestries are taken from the illustrations to the 'Atlas Japannensis', the figures in the second series are drawn from more disparate sources, including Indian miniatures, Turkish costume prints and Chinese porcelain and lacquer panels (Standen 1980 pp. 127-131). While only a handful of weaving of the Belton designs survive, numerous examples of Vanderbank's less elaborate series are known – including, within the National Trust's collection, a large panel at Clandon Park, Surrey (no. 1440604), a series at the Vyne, Hampshire, cut up to fit the walls of the Tapestry Room (no. 719698), and a small panel at Nunnington Hall in Yorkshire (no. 980694). The two tapestries at Belton were installed in the Chapel Drawing room soon after their purchase, set into wooden panelling marbled in blue, which has survived with no alteration aside from the renewal of the painted marbling. The tapestries are recorded in an inventory of 1698 as "Two pieces of Dutch hangings", in 1727 as "Two pieces of fine tapestry hanging", in 1754 as "Two pieces of fine tapestry hangings India figures", and finally in 1986 as "A pair of Soho Chinoiserie tapestries" (Belton 1983). (Helen Wyld, 2012)

Provenance

Commissioned from John Vanderbank by Sir John Brownlow (1659-97) in 1691, and installed before 1698; thence by descent to Edward John Peregrine Cust, 7th Baron Brownlow (b. 1936); given by him to the National Trust with the house and fixed contents in 1984

Credit line

Belton House, The Brownlow Collection (acquired with the help of the National Heritage Memorial Fund by The National Trust in 1984)

Marks and inscriptions

On lower galloon, towards right: IOHN VANDREBANC FECIT

Makers and roles

John Vanderbank the elder (fl. 1682 - d. 1717), workshop

References

David Mitchell, 2007: ‘The Influence of Tartary and the Indies on Social Attitudes and Material Culture in England and France, 1650-1730’, A Taste for the Exotic: Foreign Influences on Early Eighteenth-Century Silks Designs, Riggisberg 2007, pp. 11-43 Belton, 1983: unpublished report on the Belton MSS (Lincolnshire Archives), 1983 (copy at Belton House) Jarry, 1981: Madeleine Jarry, Chinoiserie: Chinese Influence on European Decorative Art, 17th and 18th centuries, New York 1981 Impey, 1977: Oliver Impey, Chinoiserie: The Impact of Oriental Styles on Western Art and Decoration, Oxford 1977 Standen, 1980: Edith A Standen, 'English Tapestries "After the Indian Manner"', Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 15 (1980), pp. 119-42 Scheurleer, 1960-62: Th H Lunsingh Scheurleer, 'Documents on the Furnishing of Kensington House', Walpole Society, vol. 38 (1960-62) Thomson, 1973: W G Thomson, A History of Tapestry from the Earliest Times until the Present Day, 3rd edition, Wakefield 1973