Pygmalion

possibly Michel Wauters (d.1679)

Category

Tapestries

Date

circa 1675 - circa 1700

Materials

Tapestry, wool and silk, 6 warps per cm

Measurements

1900 x 5710 mm

Place of origin

Antwerp

Order this imageCollection

Cotehele, Cornwall

NT 348258.1

Summary

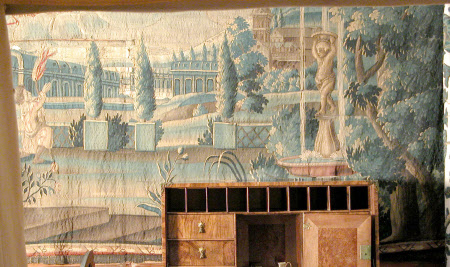

Tapestry, wool and silk, 6 warps per cm, Pygmalion from a set of three Stories from Ovid, English or Flemish, c. 1675-1700. In the centre the sculptor Pygmalion works with a hammer and chisel on a life-sized statue of a woman. To his right is the goddess Minerva wearing a helmet, a breastplate and red and blue robes and carrying a spear, leaning on the back of a chair with lions’ feet, her shield with Medusa’s head lying on the ground beside her. The figures are on a stone platform attached to a large building with marble columns on the left hand side. In the background to the right Pygmalion appears again kneeling and holding a burning torch, praying to Venus, who appears in the sky in a chariot drawn by swans. Further to the right are trees in pots and a fountain formed of a stone putto holding up a basin. In the background is a landscape with formal gardens, an extensive palatial structure and distant mountains. A section of verdure has been attached at the left hand side of the tapestry, cut following the shapes of the leaves to disguise the join. The narrow borders are composed of a band decorated with crossed ribbons, woven in imitation of a carved and gilded wooden frame. The lower and right-hand borders are integral to the main field and the upper and left-hand borders have been sewn on.

Full description

The story of Pygmalion is told in Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ as part of the song of Orpheus. Pygmalion lived on the island of Cyprus and lead a life of celibacy, so disgusted was he by the women of the island, the Propoetides, who had been condemned by Venus to live as prostitutes after denying her divinity. Shunning the company of such women Pygmalion instead sculpted for himself an ivory statue of a girl. The statue was so beautiful that he fell in love with it and treated it like a real girl, kissing and caressing the ivory and dressing the it in rich robes and jewellery. When the feast day of Venus arrived, Pygmalion, who did not dare wish that his ivory statue come to life, prayed instead that his bride would be “the living likeness of my ivory girl”; Venus understood his wish, and when he returned home and caressed the ivory statue it came to life under his kisses. The tapestry includes two scenes from the story. First, Pygmalion is sculpting his figure (which appears closer in colour to stone than ivory), accompanied by Minerva. In the background a second scene shows Pygmalion holding a torch and praying to the Goddess Venus, in her chariot drawn by swans. Wendy Hefford points out that Minerva has no place in the story of Pygmalion, but that she does appear in scenes showing another sculptor, Prometheus. Hefford suggests that the designer of the tapestry has become confused, mistaking the votive torch held by Pygmalion for an attribute of Prometheus who is credited with having brought fire to mankind (Hefford 1983, p. 104). The Cotehele ‘Pygmalion’ and the two fragments from ‘Venus and Phaon’ are part of a larger series of mythological scenes taken from both Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ and his ‘Heroides’. As many as eleven different subjects have been identified belonging to this series, which may in fact be an amalgamation of two original series: one from the ‘Metamorphoses’ (including ‘Pygmalion’) and another from the ‘Story of Sappho’ (including the story of Venus and Phaon), which appears in the ‘Heroides’ (Hefford 1983). The origin of the ‘Stories from Ovid’ has been the subject of protracted debate. As Koenraad Brosens has observed the practices adopted by many late seventeenth-century Flemish weavers, which involved circulating cartoons between different workshops, modifying cartoons by adding or removing figures, and continually amalgamating scenes from different series to customise suites, make it difficult and often impossible to pinpoint the origin and extent of such mythological tapestry suites (Brosens 2008, p. 203). Hefford suggests that when the designs for these tapestries, which originated in Antwerp, were imported to England, English dealers unfamiliar with their subjects treated the two groups as one large series (Hefford 2010, p. 275). In the early twentieth century Henry Marillier grouped together almost 100 tapestries with mythological subjects, small figures, and narrow borders like those seen on the Cotehele 'Stories from Ovid'. Since the majority of these tapestries were found in England Marillier speculated that the tapestries were of English origin and dubbed them the 'English Metamorphoses'. Very few of the pieces had marks indicating their origin, and although Marillier found one piece with an English mark, another set at Boughton House had a monogram ‘MW’, which was unknown at the time (Marillier 1930). This monogram was subsequently proved to be that of the Antwerp tapissier Michiel Wauters (Crick-Kuntziger 1935), but Marillier continued to assert that the series was English, based on further examples that appeared on the art market with the English mark (Marillier 1940). Finally Wendy Hefford made an in-depth study of the surviving tapestries and of the documentation relating to the Wauters firm. Hefford concluded that the tapestries now known as ‘Stories from Ovid’ originated with the Wauters firm in Antwerp, whose records mention many of the surviving subjects; but that the designs were subsequently copied by English weavers. Most of the English versions were reversed in relation to the originals, and Hefford also established certain physical criteria for distinguishing between the Antwerp and English versions: in England the red dyes were of a finer quality, and the warp count slightly higher. Unfortunately the three tapestries at Cotehele cannot be attributed firmly on these grounds: as Hefford notes, although the design is reversed in relation to some of the known Antwerp examples, the warp count is in between the Antwerp and English standards, and the red dyes do not fall conclusively into one category or the other (Hefford 1992). More recently however, following more protracted study of the various surviving pieces from the ‘Stories from Ovid’, Hefford has retreated from these classifications on the grounds of physical characteristics, arguing that “such distinctions cannot be maintained” (Hefford 2010, p. 275). The origin of the three tapestries at Cotehele therefore remains open to question. None of the surviving records of the Wauters ‘Ovid’ tapestries mentions a designer for the set, however Hefford has attributed the design to the little-known Daniel Janssens (1636-1682). Originally from Mechelen (or Malines), a city which traditionally specialised in the production of designs for tapestry, he was registered as a master in the city’s painter’s guild in 1660 and later spent ten years in Antwerp, returning to his native town in around 1675. Janssens produced architectural and decorative works as well as tapestry designs, though little of the former survives. He worked extensively for the Wauters firm and is known to have designed many of their most popular tapestry series including the ‘Seven Liberal Arts’, examples of which survive at Cotehele (Hefford 1983; Brosens 2008, pp. 199-206). There is another example of 'Venus and Phaon', as well as a tapestry of 'Sappho' and a some related fragments , in the National Trust's collection at The Vyne (no. 719696), and tapestries from the ‘Story of Cadmus’, also part of the larger ‘Stories from Ovid’ group, at both Lyme Park and Chirk Castle (nos. 500317, 1171318). (Helen Wyld, 2010)

Provenance

First recorded at Cotehele c. 1840; left at Cotehele when the property was accepted in lieu of tax from Kenelm, 6th Earl of Mount Edgcumbe (1873-1965) and transferred to the National Trust in 1947; amongst the contents accepted in lieu of estate duty by H M treasury and transferred to the National Trust in 1974.

Credit line

Cotehele House, The Edgcumbe Collection (The National Trust)

Makers and roles

possibly Michel Wauters (d.1679), workshop possibly Wauters, Cockx and de Wael , workshop possibly Maria Anna Wauters (c.1656 - 1703), workshop possibly English, workshop attributed to Daniel Janssens (Mechelen 1636 - 1682), designer

References

Hefford, 2010: Wendy Hefford, ‘The English Tapestries’, in Guy Delmarcel, Nicole de Reyniès and Wendy Hefford, The Toms Collection Tapestries of the Sixteenth to Nineteenth Centuries, Zürich 2010, pp. 239-294 Brosens, 2008: Koenraad Brosens, European Tapestries in the Art Institute of Chicago, New Haven and London 2008 Hefford, 1983: Wendy Hefford, ‘The Chicago Pygmalion and the “English Metamorphoses”’, The Art Institute of Chicago: Museum Studies, 10 (1983), pp. 93-117 Marillier, 1940: Henry C Marillier, ‘The English Metamorphoses: a confirmation of origin’, Burlington Magazine, vol. 76, no. 443 (Feb. 1940), pp. 60-63 Crick-Kuntziger, 1935: Marthe Crick-Kuntziger, 'Contribution à l'histoire de la tapisserie anversoise: les marques et les tentures des Wauters', in Revue belge d'archéologie et d'histoire de l'art, 5, 1935, pp. 35-44 Marillier, 1930: Henry C Marillier, English Tapestries of the Eighteenth Century, London 1930