The Fury of Athamas

John Flaxman (York 1755 - London 1826)

Category

Art / Sculpture

Date

1790 - 1793

Materials

Marble

Measurements

2200 x 1980 mm

Place of origin

Rome

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852233

Caption

This sculpture was a labour of love for John Flaxman (1755–1826), one of the most accomplished sculptors of his time. It was commissioned in Rome by Frederick Augustus Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol (1730–1803), for his house at Ickworth in Suffolk but was seized by Napoleonic troops on its journey to England in 1798. The sculpture took Flaxman more than three years to complete but, unfortunately for the artist, in his enthusiasm for the project, he had struck a poor bargain. He was paid £600 for the piece, but the marble alone had cost him £500. The complex, horrifying and tragic subject, The Fury of Athamas, is little known, but depicts the mythical king Athamas killing his son and derives from a tale in the book of Metamorphoses by the Roman writer Ovid (43 BC–c.AD 18). The sculpture finally made its way to Suffolk in the 1820s, when Hervey’s son repurchased it for the original sum of £600.

Summary

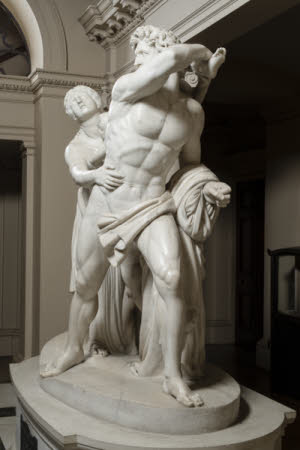

Sculpture, marble; The Fury of Athamas; John Flaxman; Rome, 1790-93. The Fury of Athamas relates a story from the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which Juno queen of the gods caused king Athamas to go mad. In his fury he believed his wife Ino and their sons Learchas and Melichertes to be lions, chasing them through the house before seizing Learchas and dashing him to the ground. In the sculpture, Athamas has grabbed Learchas by the leg whilst the poor child clings desperately to her mother, who tries in vain to restrain her husband. In Ovid’s story, Ino fled with her surviving son Melichertes, plunging with him from a cliff into the ocean, where they are transformed into the sea gods Leucothoë and Palaémon. The sculpture was commissioned by Frederick Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry, in Rome in 1790 from the young English sculptor John Flaxman. The fee agreed for this ambitious work in the end barely covered Flaxman’s costs of materials and labour, but he regarded the commission as a life saver at a time when there was very little work for artists in Rome, as well as an important demonstration of the young sculptor's ability to create major compositions. It is a key work in the story of neo-classical sculpture in Britain and Europe, recent research having drawn new attention to its influence on artists working in Rome, including the sculptor Antonio Canova. Along with the remainder of the Earl Bishop’s Roman collections, the Fury of Athamas was confiscated by the French when they invaded Rome in 1798. It somehow ended up in Paris, where the 4th Earl’s son Frederick William Hervey, 5th Earl and 1st Marquess of Bristol (1769-1859) bought it back in the 1820s, to serve as the centrepiece in the Entrance Hall at Ickworth.

Full description

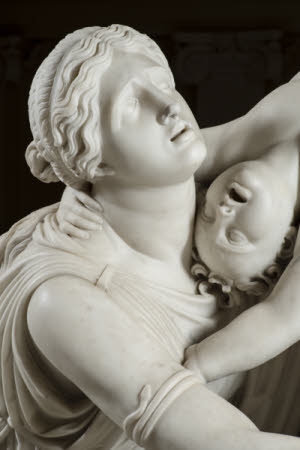

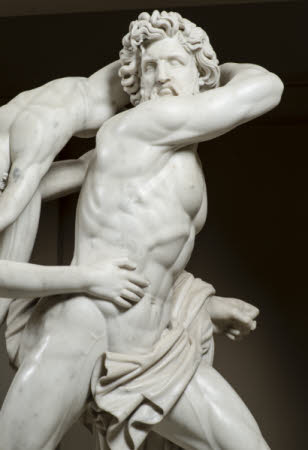

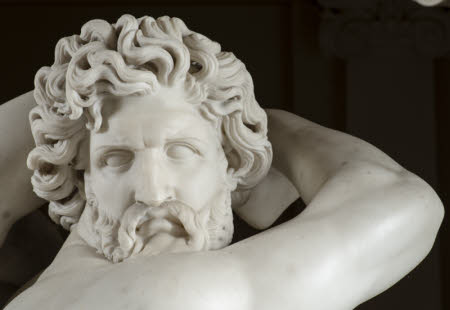

Sculptural group by John Flaxman depicting the Fury of Athamas, with the figures of Athamas, his wife Ino and their children Learchas and Melicertes. The naked figure of Athamas strides forward, his head turned sharply to his right to reveal an implacable and furious gaze. His right hand is clenched, with a swag of drapery over the arm. With his left hand he has seized his son Learchas by the ankle and is about to dash him to the ground. Learchas is screaming, scrabbling to hold onto his mother Ino, one hand wrapped around her neck. Ino struggles with her left hand to detach her husband’s hand from their son’s leg, whilst with her right hand she holds Athamas by his belly, in an attempt to restrain him. Ino is dressed in a classicising robe, her hair partly done up in a bun at the back of her head, the remainder cascading down her back. The couple’s second son Melicertes holds desperately on to his mother. The sculpture is on an integral oval base and is set on a later wooden pedestal with bowed ends and, in the centre of the front long side, an inscribed bronze tablet. The section of drapery covering Athamas’s groin has been carved separately; it has often been stated that this was added in the nineteenth century for reasons of propriety. There is a break in Ino’s nose and a crack in her right foot, across the sandal. There is also some abrasion and small breaks in Ino’s drapery, for example just below Melicertes’ right hand. John Flaxman’s Fury of Athamas is one of the monuments of neo-classical sculpture and a key work in the career of this leading British sculptor, who enjoyed a European-wide reputation during his lifetime. Neo-classicism, a style that became popular in the period from c. 1750 to c. 1820, was based on close study of the art of ancient Greece and Rome. Its greatest exponent in sculpture was Antonio Canova (1757-1822) but Flaxman was a leading figure in the movement, as was the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen ( 1770-1844). The horrendous subject of the sculpture, the murder by a father of his own son, has only very rarely been depicted in art – just one other sculpture is currently known, a small marble group attributed to the Milanese sculptor Gaspare Vismara (fl. 1610-51) in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (Inv. A.64-1949). The story, as depicted by Flaxman, is taken from the Roman poet Ovid’s long poem Metamorphoses (IV. 420-562). In essence, it is a tale of the pitiless jealousy and anger of Juno (Greek, Hera), queen of the gods. Athamas was king of Orchomenus in Boeotia in central Greece. In some other tellings of his story he angered Hera by abandoning Nephele, the woman she had commanded him to marry, for Ino, the daughter of king Cadmus. But in Ovid’s telling Juno was driven to rage by Ino’s contentment and pride in her marriage, after she and her husband Athamas had nurtured and brought up Bacchus, the child of Ino’s sister Semele with Juno’s often errant husband Jupiter, king of the gods. Juno descended into the underworld to seek out the Furies, whom she instructed to carry out her bidding; the fearsome hags duly blocked Athamas and Ino in their house, tossing onto them serpents carrying a venom that drove Athamas into a maddened fury. He took his wife and children for a lioness and her cubs, pursuing them through the house and seizing the baby Learchas from his mother’s breast, swinging him around in the air and then shattering his skull on the floor. Ino, now herself driven to distraction, fled with her surviving son Melicertes until she came to a headland, from which she jumped with her child into the sea. At this point Venus, driven to pity by the suffering that the innocent woman had undergone, urged her uncle Neptune to turn them into sea-gods, which he duly did. Thus Ino was transformed into Leucothoë and Melicertes into Palaémon. In a final act of spite, Juno transformed into stone Ino’s sorrowing friends and followers, who had gathered on the headland to lament their loss and to curse the goddess. As for Athamas, he was forced to flee Boeotia but seems to have met no further punishment, settling in Thessaly. The sculpture is by far the most important work of sculpture known to have been commissioned by Frederick Hervey (1730-1803), 4th Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry, known as the Earl Bishop. The Earl Bishop was a major patron of sculptors and painters in Rome, but the Fury of Athamas is one of very few works from his sculpture collection that can be traced today, not least thanks to the circumstances of its commissioning. John Flaxman and his wife Maria arrived in Rome in December 1787, remaining in the city until 1794. These were crucial years for the young sculptor, who used his time in Rome to study ancient and modern sculpture, and whose years in Italy were fundamental in helping the young sculptor fully to realize his vision as a neo-classical artist. It was during his Roman period that he made his highly influential outline drawings illustrating Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, as well as an extensive set of drawings to Dante’s Divine Comedy. These were published in the form of engravings which circulated throughout Europe and helped secure the sculptor's European reputation. Whilst in Rome John Flaxman also made some major marble sculptures, the group of Aurora visiting Cephalus on Mount Ida for Thomas Hope in 1789-90 (Port Sunlight, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Irwin 1979, pp. 54-55, Marpessa of c. 1790-94 (Royal Academy; Bindman 1979, p. 101, no. 114). He also began work on a commission from the banker Thomas Hope for a monumental group depicting Hercules and Hebe, the torso of Hercules to be based on the celebrated antique torso known as the Belvdere Torso. Flaxman worked on this figure from March to December 1792, producing a full-scale plaster model (University College London; on loan to National Trust, Petworth), but failing to complete the marble. All these works also show Flaxman’s typically neo-classical predilection for rather obscure subjects. Flaxman himself recounted the story of the commissioning of the sculptural group and the selection of the unusual subject, in a letter of 15 April 1790 to the painter George Romney, written as the sculptor had been preparing to return to Britain: ‘One morning Lord Bristol called to see what I have done here, and ordered me to carve in marble for him, a bas relief I have modelled here, between eight and nine feet, and near five feet high: representing Amphion and Zethus delivering their mother Antiope from the fury of Dirce and Lycus; it is my own composition, taken from a different point of time, but the same story as the group of the Toro Farnese, which you well know. I refused this work, notwithstanding the price would have been five hundred guineas, and informed his lordship I could not possibly remain longer here, unless I should be employed to execute a work that might establish my reputation as a sculptor. His lordship applauded my resolution, and immediately ordered me to execute a group in marble, the figures as large as the Gladiator, from a sketch in clay which I had made; the subject of which is, the Madness of Athamas, in which he believes his wife Ino to be a tigress, and her children her whelps; when after coursing them round the hall, he seizes the youngest from its mother’s breast, and throws it on the ground. The story is in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, and the group consists of Athamas, Ino, and two small children.’ Flaxman went on to explain that arrangements for payment had been made with a Mr Bunce and, then, ‘Forgive my vanity in telling you that I was particularly recommended in this work to Lord Bristol by Mr. Canova, who has done the monuments of two Popes, and other excellent works, and is esteemed here the best sculptor in Europe.’ (Romney 1830, pp. 204-07). The commissioning of the Fury of Athamas has sometimes been used against the Earl Bishop since Flaxman, who laboured on the sculpture for more than three years, greatly underestimated the cost of making the sculpture and, as a result, barely covered his costs for materials and the labour of his assistants. Whilst there is no doubt that the patron obtained a very good bargain, the fault clearly lay in the first place with Flaxman, for underestimating his costs. He was certainly desperate for the work and extremely keen to obtain a commission that would help to bolster his career. There is no evidence that the Earl Bishop was in any way tardy with his payments to the sculptor. A note to the painter Jacob More, who lived in Rome, also makes clear that he greatly appreciated Flaxman and his talents. Lord Bristol informed More that he had commissioned the sculpture from Flaxman for a price of about 600 guineas (£630), asking that ‘Mr More will be so good as to supply him gradually with the sums necessary and to give his Genius every encouragement Flaxman laboured over the sculpture for some three years. He had completed a full-size model in terracotta by late 1790, as he reported to his parents in a letter of 7 October 1790: ‘my great group in clay is on the point of finishing, two or three weeks more will complete it, and I think for a group as large as the Laocoon, finished every part from Nature in the best manner that I am able.’ (Irwin 1979, p. 57). Later in the same letter, he reiterated the importance of this commission for his career: ‘if I ever expect to be employed on great works, it is but reasonable that I should show the world some proof of my abilities, otherwise I cannot reasonably expect employment of that kind.’ He travelled to Carrara in April 1792 to select the block of marble and, once delivered, studio assistants began working on it. Flaxman wrote in a letter of 23 November 1792 that he was ‘now actually giving the last touches’ (Irwin 1979, p. 224, note 10). Flaxman would not have spent all his time on the sculpture; it was dVaere (1755-1830) who attended the Royal Academy Schools in 1786 and in 1787 was sent to Rome by Josiah Wedgwood, to make models after antique subjects under Flaxman’s supervision, for example one of the famous Borghese Vase. De Vaere returned to London in 1790, so his assistance must have been concentrated on the preparation of the full-size clay model, which Flaxman reported was nearing completion in late 1790. After his return to Britain, De Vaere worked for Wedgwood and subsequently the Coade manufactory. The Fury of Athamas was the first neo-classical sculpture to seek to emulate the grandeur of ancient full-size figure groups, notably the Laocoön, the celebrated ancient marble group in the Vatican museums that depicts the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons being killed by sea serpents, sent by the goddess Minerva. The sculpture has been described as having ‘a significant place as the first freestanding colossal marble of four figures depicting violent movement that sets out to rival the most famous Hellenistic sculptures, such as the Niobids and the so-called Paetus and Arria.’ (Dean Walker in Bowron and Rishel 2000, p. 221). In creating his composition, Flaxman not only looked to these great multi-figural groups for their concept, but also borrowed specific elements from a variety of sources. The first source for the sculpture, referred to in Flaxman’s letter to Romney, was though the sculptor’s own now lost relief, in plaster or terracotta, depicting ‘Amphion and Zethus delivering their mother Antiope from the fury of Dirce and Lycus’. It was this relief that the Earl Bishop wanted the sculptor to create for him in marble, a request which Flaxman refused. He instead persuaded Lord Bristol to commission a marble group based on a small clay sketch he had made of the Fury of Athamas. Both this model and the larger relief are lost, but the design of the relief is very well preserved in a drawing by Flaxman recently on the art market (Libson 2013, pp. 41-43). There are a number of parallels between the drawing and the Fury of Athamas; firstly the figure of Amphion at the centre of the design looks towards that of Athamas, with his legs wide apart, his head sharply turned and one arm raised. It has been suggested that the figure may have been based on a figure in a Roman sarcophagus in the Palazzo Accoramboni in Rome, recorded in a drawing by William Ottley in the British Museum (2006,0515.45; illustrated Libson 2013, p. 41), which is in fact a tracing of a lost drawing by Flaxman himself. Whilst there are certainly parallels with the sarcophagus figure, so far as the figure of Athamas is concerned, it is based on the ancient sculpture known as the Ludovisi Gaul or Paetus and Arria, a second-century A.D. Roman copy of a Hellenistic sculpture formerly in the Ludovisi collection, and now on display in Palazzo Altemps in Rome (Haskell and Penny 1981 and 2024, no. 68). The sculpture shows a man who has just killed a woman, whose body he supports with his left hand, whilst his raised right hand holds a sword with which he is about to kill himself. The subject of the work has been variously identified over the centuries, suggestions including a Gaulish warrior and his wife, and the Roman conspirator Paetus and his wife Arria. When seen from the side, the figure of the man is in its poseall but identical to that of Athamas, with the legs outstretched, the head turned sharply to the right and the right arm held above the face. The actual gesture of grabbing his son by the ankle refers however to another second-century sculpture from the Farnese collection, now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples (Inv. 5999; Gasparri 2010, III, pp. 29-32, no, 5; Pavanello 2019, p. 316, no. 28). This figure of a man striding forwards, holding by the leg over his shoulder the body of a small child, has likewise been given various titles over the years, including Hector and Troilus, Athamas and Learchas, Neoptolemus and Astyanax and Commodus as Gladiator. The Farnese collection was transferred from Rome to Naples between 1787 and 1792, so Flaxman would certainly have had the opportunity in Rome to study the sculpture, as well as the smaller bronze reductions that were made from it, such as one in the Musei Civici in Ferrara (Varese 1975, p. 142, no. 130). It is this sculpture to which he was referring in his letter to Romney, when he wrote that his group would be ‘as large as the Gladiator’ – the name by which the sculpture then in Palazzo Farnese went in the late eighteenth century. Flaxman would also, when conceiving his group, have been aware of a more modern source, the Italo-Flemish sculptor Giovanni Bologna (Giambologna, 1529-1608)’s multi-figured sculptural groups, notably the 'Abduction of the Sabine woman' in the Loggia dei’ Lanzi in Florence, in which the striding action of the man holding up the woman closely matches that of Athamus. Flaxman made a careful drawing, now in the Victoria & Albert Museum, of Giambologna’s group from precisely the angle in which the striding position of the man is maximised (Irwin 1979, p. 59, fig. 72). Finally, the face of Athamas is essentially based on that of Laocoön in the famous group in the Vatican. The heavily draped figure of Ino on the other hand, as well as that of Antiope in Flaxman’s lost relief, is clearly borrowed from the figure of Niobe with her daughter in the celebrated group of Niobids installed in 1781 in the Uffizi, Florence (Haskell and Penny 1981 and 2024, no. 66.). Flaxman drew this figure twice in his Italian sketchbook, begun in 1787, in the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven (Irwin 1979, p. 58, fig. 71). Hen was evidently particularly taken with he Niobids, writing that ‘beautiful nature was chosen by the artist and copied with so much spirit, judgment and truth of anatomy and outline, with a delicacy of execution, that when seen in proper light the naked parts seem capable of motion, the draperies are of fine cloths, light, beautifully disposed to contrast the limbs and shew them, as well as to add dignity to the figures.’ (Irwin 1979, p. 43). Flaxman has taken from the figure of Niobe her heavy dress, a type known as the ‘chiton’ in Greek, her pose, pushing forward with her left leg, her hair, including the hair falling down her back and, finally, the woman’s stylised expression of noble grief. The Fury of Athamas is a remarkable composition, in which is distilled the excitement felt by an ambitious young sculptor who has at last come face to face with the famous monuments of antique sculpture that were to be seen and experienced in such profusion in Rome. The composition has a strong sense of movement, driven by the way in which the main figures stride forward almost as if in step, the draperies accentuating the driving movement, whilst the flying figure of the unfortunate Learchas acts as a bridge between the two main figures. The space between the two figures plays an extremely important part in the composition. The tension within the group is dramatically increased by the way in which the driving sense of movement is brought to a sudden halt by the single vertical element in the entire composition, the left leg of Athamas at the outer edge, which acts like a full stop; even Athamas’s foot has been confined by the sculptor within the barrier formed by the edge of the marble base. The expressions on the faces of the protagonists express the full gamut of expressions, a cold rage for Athamas, for Ino a classic nobility, whilst the two sons as they scream their terror point towards a greater emotionalism. The very different hairstyles help to emphasise this differentiation between the figures, the snake-like locks of Athamas a potent remimder of the serpents let loose by the Furies. The 4th Earl of Bristol left Rome late in 1790 – he was in Ireland by November of that year – so would have had plenty of opportunity to see the development of the clay model for the group, mentioned by Flaxman as all but finished in his letter of October 1790. He remained full of excitement at his commission, in letters from March 1792 to his daughter Lady Erne describing Flaxman as ‘the modern Michael Angelo’ and suggesting that he ‘will probably rise to be the first Sculptor in Europe – exquisite Canova not excepted’ (Childe-Pemberton 1925, II, pp. 438-39). By the time he was next in Rome, November 1794, the Fury of Athamas would have been completed some time before, whilst the Flaxmans had left Rome in June, as fears of French invasion grew. The sculpture though evidently fully met the Earl Bishop’s expectations. He was reported as boasting that it ‘exceeded the Laocoön in expression’ and ‘was the finest work ever done in sculpture.’ (Irwin 1966, pp. 63-64). The Earl Bishop would subsequently commission for Ickworth the friezes in terracotta and other materials featuring episodes from Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, many of which were based on Flaxman’s illustrations (Marshall 2024). Despite the Earl Bishop’s enthusiasm for his sculpture, he did not get round to having it sent home. It was still in Rome when, in March 1798, the French army under General Berthier entered the city and confiscated Lord Bristol’s entire property (Figgis 1993). Despite furious attempts by him to recover the collections, some items were taken to France, including it seems the Flaxman, the remainder staying in Rome. Following the death of the Earl Bishop in 1803, a sale of his remaining collections in the city was organised in Rome, in 1804 or 1805 (Figgis 1993), which did not include the Fury of Athamas, bought in Paris by his son the 5th Earl, perhaps in 1820, when the Hervey family spent much of the year living in the French capital. It was first recorded at Ickworth in May 1829 when, on 15th May, the diarist Henry Crabb Robinson (1775-1867) drove with his ‘niece and grand-niece to see Lord Bristol’s new house’, which was evidently still some way from completion and furnishing (Crabb Robinson 1869, II, pp. 418-19). According to Crabb Robinson, Flaxman’s sculpture, which he described as ‘a noble performance’, was the only work of art that the house contained at this point in time. Crabb Robinson criticized the proportions of the head and neck of Ino, but conceded that ‘There is vast expression of deep passion in all the figures.’ Crabb Robinson’s criticisms presage later attitudes towards Flaxman’s sculpture, which tended to suggest that the artist overstretched himself in his attempt to create a work with a violent subject matter on a grand scale and that the sculpture should be judged a failure. Margaret Whinney was especially critical, writing that the artist’s ‘intellectual equipment was not enough to distil the drama to the minimum terms […] and his technique, though wonderfully matured by his contact with classical sculpture, was not sufficiently controlled to cope with design on so large a scale […] the group remains loose and undisciplined, with none of the tautness of outline of Canova’s Hercules and Lichas.’ It is certainly true that Flaxman did not receive further commissions for large-scale violent subjects and that it seems that ‘contemporaries, especially potential patrons, valued Flaxman’s achievement more highly in the area of gentler themes.’ (Irwin 1979, p. 58). The Fury of Athamas has remained relatively little known, in part because most of its life has been spent in an English country house. In addition, whilst in his lifetime Flaxman was hardly less famous than his contemporary Antonio Canova, this is certainly not the case today. Nevertheless, John Flaxman’s Fury of Athamas is today increasingly accepted as one of the masterpieces of late eighteenth-century European sculpture. More recent scholars have demonstrated that the great tragic figure group was certainly not regarded as a failure at the time of its creation. In fact it seems to have had a considerable influence on artists in Rome. In 1801 the Roman painter Arcangelo Migliorini (1779-1865) made an enormous painting of the same subject, closely based on Flaxman’s group (Accademia di San Luca, Rome). Flaxman enjoyed close relations with Antonio Canova, who in fact recommended the sculptor to Lord Bristol, and in whose studio it has been suggested the large clay model for the Fury of Athamas was probably made. Canova clearly looked very closely at this work for his sculpture of Hercules and Lichas, which depicts the classical hero holding a messenger Lichas by the ankle as he prepares to hurl him into the sea (Galleria Nazionale d’arte moderna, Rome; Pavanello 1976, no. 131, Pls. 29-30). In fact, all three of the large-scale figural compositions made by Flaxman during his Roman years, the Fury of Athamas, the Cephalus and Aurora and the Hercules and Hebe, would prove influential for Antonio Canova ‘s own later works (Grandesso 2009, pp. 47-48). The Fury of Athamas has always stood in the Entrance Hall at Ickworth. The Hall was completed for the 1st Marquess of Bristol in 1827 by the architect John Field, who screened the staircase from the hall by means of a thick dividing wall, against which stood the marble group. It was presumably in this position when Crabb Robinson saw it in 1829, and in 1838, when John Gage Rokewode recorded the sculpture as in the Entrance Hall. When the staircase was remodelled by the architect A.C. Blomfield in 1909-11, the wall was demolished and a further pair of giant columns installed as supports. The Fury of Athamas was placed on a newly-designed pedestal and moved to the rear of the newly visible Staircase Hall, where it has remained ever since. Jeremy Warren December 2025

Provenance

Commissioned by Frederick Augustus Hervey, the Earl-Bishop (1730-1803) in Rome in 1790 for the sum of 600 guineas (£630); confiscated at the behest of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798 before being purchased in Paris and brought back to Ickworth by Frederick William Hervey, 1st Marquess of Bristol (1769-1859), in the early 1820s; acquired by the National Trust in 1956 under the auspices of the National Land Fund, later the National Heritage Memorial Fund.

Credit line

Ickworth, The Bristol Collection (acquired through the National Land Fund and transferred to The National Trust in 1956)

Marks and inscriptions

Bronze tablet on pedestal: THE FURY OF ATHAMAS. / JOHN FLAXMAN, R.A.

Makers and roles

John Flaxman (York 1755 - London 1826), sculptor

References

Smith, John Thomas, 1766-1833 Nollekens and his times: 1828., II, p. 440 Flaxman, John, Lectures on sculpture., MDCCCXXIX. 1829, p. xvi Cunningham, Allan, 1784-1842. lives of the most eminent British painters, sculptors, and architects. [1830-1833], III, p. 303 Romney 1830: John Romney, Memoirs of the life and works of George Romney, London 1830, pp. 204-07 Gage, 1838: John Gage. The history and antiquities of Suffolk: Thingoe hundred. London: Printed by Samuel Bentley, Dorset Street; Pub.John Deck, Bury St. Edmund’s, and Samuel Bentley, Dorset Street, 1838., p. 306 Crabb Robinson 1869: Henry Crabb Robinson, ed. Thomas Sadler, Diary, reminiscences, and correspondence, 3 vols., London 1869, II, pp. 418-19 Avray Tipping 1925: H. Avray Tipping, ‘Ickworth -II. Suffolk. The seat of the Marquess of Bristol’, Country Life, 7 November 1925, pp. 698-705, p. 704, fig. 4 Childe-Pemberton 1925: William S.Childe-Pemberton, The Earl Bishop: the life of Frederick Hervey, Bishop of Derry, Earl of Bristol, 2 vols., London 1925, II, pp. 417-19 Constable 1927: W.G. Constable, John Flaxman 1755-1826, London 1927, pp. 37-41, p. 85, Pl. XII Hussey, 1955: Christopher Hussey, ‘Ickworth Park, Suffolk: the seat of the Marquesses of Bristol’, Country Life, 10 March 1955, pp. 678-81, pp. 680-81, fig. 5 Irwin 1966 David G. Irwin, English Neo-Classical Art;studies in inspiration and taste, London 1966 , pp. 63-64, Pl. 75 Rosenblum 1967: Robert Rosenblum, Transformations in Late Eighteenth Century Art, Princeton 1967, p. 14, fig. 8 Fothergill 1974: Arthur Brian Fothergill, The Mitred Earl: an eighteenth-century eccentric. London 1974, p. 130 Ford 1974: Brinsley Ford, 'The Earl Bishop: an eccentric and capricious patron of the arts', Apollo 99, June (1974): pp. 426-34, pp. 430-31, fig. 8 Varese 1975: Ranieri Varese, Placchette e bronzi nelle Civiche Collezioni, exh.cat., Palazzo di Marfisa d’Este, Ferrara 1975 Pavanello 1976: Giuseppe Pavanello, L’opera completa del Canova, Milan 1976 Bindman 1979: David Bindman, ed., John Flaxman, exh. Cat., Royal Academy of Arts, London 1979, p. 28, fig. III.8 Irwin 1979: David Irwin, John Flaxman 1755-1826 - Sculptor Illustrator Designer, London 1979, pp. 54-58, fig. 69 Haskell and Penny 1981: Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique, The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500 - 1900, New Haven and London, 1981 Symmons 1984: Sarah Symmons, Flaxman and Europe. The Outline Illustrations and their Influence, New York/London 1984, pp. 71-74, Pl. 14 Andrew 1986: Patricia R. Andrew, ‘Jacob More and the Earl-Bishop of Derry’, Apollo, pp. 88-94, p. 92 Whinney 1992: Margaret D. Whinney, Sculpture in Britain, 1530-1830, Yale University Press, 1992, pp. 342-44, fig. 246 Poulet 1991: Anne L. Poulet, ‘Clodion's Sculpture of the "Déluge"’, Journal of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston , 3 (1991), pp. 51-76, p. 59 Figgis 1993: Nicola F. Figgis, ‘The Roman Property of Frederick Augustus Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry (1730-1803)’, Walpole Society, 55 (1989/1990, published 1993), pp. 77-103 Ingamells 1997 J. Ingamells, Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy: 1701-1800, New Haven/London 1997, p. 128 Bowron and Rishel 2000: E. P. Bowron and J. J. Rishel, eds., Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century, exh cat., Philadelphia Museum of Art, March 16-May 28, 2000 and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, June 25-September 17, 2000, Philadelphia 2000, p. 221, fig.100 Trusted 2008: Marjorie Trusted, The Return of the Gods Neoclassical Sculpture in Britain, exh.cat. Tate Britain, London, 2008, p. 7, fig. 3 Androsov, Mazzocca and Paolucci 2009: S. Androsov, F. Mazzocca and A.Paolucci, eds., Canova. L’ideale classico tra scultura e pittura, exh.cat., Musei San Domenico, Forlì, Milan 2009 Gallo 2009: Daniela Gallo, Modèle ou Miroir? Winckelmann et la sculpture néoclassique, Paris 2009, pp. 57-59, fig. 32 Grandesso 2009: Stefano Grandesso, ‘La fortuna dell’Ebe canoviana in scultura come personificazione della grazia giovanile e prototipo delle statue “aeree”’, in Androsov, Mazzocca and Paolucci 2009, pp. 45-57, pp. 47-48 Roscoe 2009: I. Roscoe, E. Hardy and M. G. Sullivan, A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain 1660-1851, New Haven and Yale 2009, pp. 443 and 458, no. 246 Gasparri 2010: Carlo Gasparri, ed., Le sculture Farnese, 3 vols., Milan 2010, III, p. 32, note 9 Grandesso 2013: Stefano Grandesso, ‘ Lord Bristol Mecenate delle Arti e della Scultura moderna’, Studi Neoclassici, 1 (2013|), pp. 117-26, pp. 121-23, fig. 7 Libson 2013: Lowell Libson Ltd 2013, British Painting sand Works on Paper, London 2013, pp.41-42 Guilding 2014 Ruth Guilding, Owning the Past : Why the English collected Antique Sculpture, 1640 - 1840, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Yale University Press, 2014, p. 257, fig. 243 Pavanello 2019: Giuseppe Pavanello, Canova e l’antico, exh. cat., Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, Milan 2019, p. 316 Leone 2022: Francesco Leone,'Antonio Canova. La vita e l'opera', Rome 2022, p. 368, fig. 96 Casola 2023: Tiziano Casola, “We Romans”. Le communità di artisti anglo-romani tra XVIII e XIX secolo, Rome 2023, pp. 124-25 Casola 2023: Tiziano Casola, ‘La scultura in Accademia al tempo di Canova’, Canova: studi e ricerche, vol. 1 (2023), pp. 103-19, p. 112 Haskell and Penny 2024: Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, revised and amplified bv Adriano Aymonimo and Eloisa Dodero, Taste and the Antique. The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500-1900, 3 vols., Turnhout 2024 Marshall 2024: Sebastian Marshall, ‘Relief in the round: terracotta classicism and the Homeric friezes of Ickworth House’, Sculpture Journal, 33, 3 (2024), pp. 355-81, p. 365