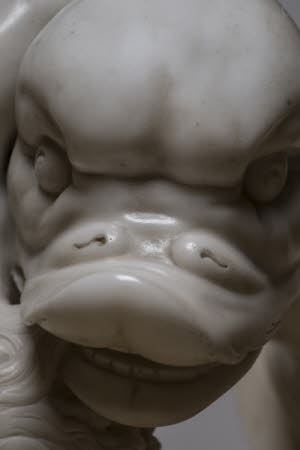

The Boy on a Dolphin

Joseph Nollekens, RA (London 1737 – London 1823)

Category

Art / Sculpture

Date

circa 1766

Materials

Marble

Measurements

60 x 36 x 20 cm

Place of origin

Rome

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852226

Summary

Sculpture, marble; The Boy on a Dolphin; Joseph Nollekens (1737-1823); Italy, Rome, c. 1766. A sculpture recounting a story told by the ancient Greek writer Aelian of how a young boy in the Greek city of Iasos and a dolphin struck up a close friendship, until the boy accidentally impaled himself on the dolphin’s spine and died. The stricken dolphin brought the boy to the shore and beached itself. The model was a sculpture now in the Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, that appeared in Rome in the workshop of the Roman sculptor and restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (c. 1716-1799) and was said at that time to have been made by a pupil of the great painter Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio, 1483-1520). It is sometimes now variously thought to have been made by a seventeenth-century Roman sculptor or by Cavaceppi himself. The British sculptor Joseph Nollekens (1737-1823), who was living in Rome in the 1760s and knew Cavaceppi well, made at least five copies of the sculpture for British patrons. This version, commissioned around 1766 by Frederick Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry (1730-1803), was formerly at the Earl Bishop’s seat in Northern Ireland, Downhill.

Full description

A marble group of a boy upon a dolphin. The child is shown dead and naked, his body lying akimbo upon the twisted coils of the dolphin’s body, the arms spread out, head hanging downwards, legs crossed. There is a bleeding wound in the right breast of the boy. The dolphin’s head is to the right of the head of the boy, whose feet rest upon the dolphin’s tail. The sculpture is mounted on a circular socle, that tapers towards the top and in turn has beneath it a rectangular base. The sculpture is displayed upon a triple columnar base formed from coloured marble columns. Some damage to the sculpture: the fingers of the boy’s left hand are all broken off, and the top edge of the socle is also broken around this point. When the group was published in 1841, it was stated that the sculpture could be rotated on its pedestal, ‘it turns upon a pivot so as to be readily viewed in all points of sight’. The sculpture is a copy, by the British sculptor Joseph Nollekens, of a work that enjoyed a brief moment of fame in late eighteenth-century Rome, when it passed through the workshops of the restorer, sculptor and dealer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (c. 1716-1799). Cavaceppi illustrated the sculpture in his 'Raccolta d’antiche Statue' published in 1768 (I, Pl. 44), describing it as a depiction of a young boy inadvertently killed by one of the spines of a dolphin, who then carries the body to land. He boldly claimed the sculpture to be nothing less than the work of the great painter Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio, 1483-1520), executed by his pupil Lorenzetto (Lorenzo di Lodovico di Guglielmo, 1490–1541). This belief was presumably based on a letter sent by Raphael’s friend Baldassare Castiglione after the painter’s death, asking if another friend and painter Giulio Romano still had ‘the little boy in marble… by the hand of Raphael’. The prime version of the design, the one illustrated by Cavaceppi, was at the time of his publication in the collection of Jacques-Laure Le Tonnelier, bailli de Breteuil (1723-1785), a noted collector who spent much of his life in Rome, as ambassador to the Holy See for the Sovereign order of Malta, the Knights of Saint John. At some point the sculpture passed to a British collector of antiquities, Lyde Browne (died 1787), who sold the sculpture with much of the rest of his collection to Catherine II, Empress of Russia. The sculpture is now in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg (Inv. 270; Androsov 2008, no. 58). The subject is derived from a story told by the Greek Roman author Aelian (Claudius Aelianus, c. 175-c. 235 AD), in his work ‘De Natura Animalium’, or ‘On the Nature of Animals’ (VI.15). Aelian recounted the story of how a young Greek boy in the city of Iasos, situated on the coast of modern Turkey, and a dolphin developed a close friendship. The boy and the mammal would sport together, swimming side by side whilst sometimes, like a rider mounting a horse, the boy would get onto the dolphin’s back and the dolphin would carry him out to sea and back to the beach. But one day the boy,exhausted by the play,flopped on his belly onto the back of the dolphin, only to be accidently transfixed by the animal’s back spine. Blood gushed forth and the boy quickly died. The dolphin, when it felt the unaccustomed weight of the boy and perceived the water turning red around it, was stricken with grief and carried the boy’s body up to the beach, where the dolphin beached itself and so also expired. A version of the same story is told by the writers Pliny (Natural History, IX.8) and Plutarch (Moralia, 984E), Pliny naming the boy Hermia. According to Aelian, the people of Iasos built a single tomb for the boy and the dolphin, with at its head a monument of a handsome boy riding a dolphin. The city also had coins struck in silver and bronze commemorating the fate of the young man and the animal; indeed there are coins from Iasos that show a boy on a dolphin and that are inscribed Hermias. There is no firm consensus as to the artist who did sculpt the version now in the Hermitage, except that nobody seriously believes it was designed by Raphael and carved by Lorenzetto. In the most recent catalogue of Italian sculpture in the Hermitage, the traditional attribution to Lorenzetto was rejected by Sergej Androsov, although the sculpture continues to be officially labelled as a work by him. Androsov thought it more likely that the sculpture was instead made around 1600 in Rome, conceivably by an otherwise largely unknown sculptor Giulio Cesare Conventi (1577-1640), by whom a marble sculpture of the subject was recorded in Palazzo Ludovisi in Rome in the seventeenth century. But the subject is found elsewhere in art made around this time, for example a small bronze in the civic museum collections in Ferrara (Varese 1975, no. 166). The American scholar Seymour Howard on the other hand in an article on the sculpture and its copies believed it to have been made by Bartolomeo Cavaceppi himself, maintaining this attribution in a catalogue entry for the copy of the sculpture at Broadlands (Bowron and Rishel 2000, no. 141). The several copies of the Boy on a Dolphin are thought all to be the work of the British sculptor Joseph Nollekens (1737-1823), who in 1762 had travelled to Rome, where he quickly became occupied with the restoration of antiquities, the main business of Bartolomeo Cavaceppi. Nollekens is thought to have worked for Cavaceppi and the two men’s studios were situated close to each other. Nollekens was commissioned in 1764 by Viscount Palmerston to make a copy of the ‘Boy on a Dolphin’, today at Broadlands (Howard 1964, figs. 102; Bowron and Rishel 2000, no. 141, entry by Seymour Howard). Several other copies were quickly made for British noblemen, the largest for Lord Exeter, placed on a pedestal decorated with Bacchic scenes, today at Burghley (Howard 1964, fig. 3; Kenworthy-Browne 1979, fig.2; Bignamini and Hornsby 2010, I, p. 295). Another version in marble is at Althorp and another was formerly at Castletown in Ireland, whilst a terracotta version made for David Garrick is now lost. A plaster model, on which all these copies were presumably based, was in the auction sale held after Nollekens’ death in 1823 (Christie’s, 4 July 1823, lot 9 ‘A boy on a Dolphin, after Raffaelle’), but plaster versions are also known to have been once owned by the painters Anton Raphael Mengs (1729-1779) and Angelika Kauffmann (1741-1807). The marble version at Ickworth must have been commissioned from Nollekens by Frederick, 4th Earl of Bristol, the ‘Earl-Bishop’, presumably in 1766, when he made his first known visit to Rome. The sculpture was long kept at the Earl’s Irish house Downhill, where it was rediscovered in the 1820s. In 1841 the sculpture was illustrated and discussed in the popular publication ‘The Penny Magazine’. By the early nineteenth century all of the examples of the sculpture in private collections in Britain seem to have become forgotten and, because of its supposed association with Raphael, the model had become something of a legend. Therefore the rediscovery of the Earl Bishop’s version at Downhill was greeted with some excitement. In 1851 much of Downhill was destroyed by fire and in the 1850s the owner of the house and collection Sir Henry Hervey Bruce, 3rd Baronet (1820-1907) lent the sculpture to three major loan exhibitions, in Dublin (1853), Paris and the celebrated Art Treasures Exhibition held in Manchester in 1857. For the Dublin exhibition, the Boy on a Dolphin was exhibited along with a whole series of other sculptures at Downhill, all or most of which must have been acquired by the Earl Bishop. Unfortunately none other than the Boy on a Dolphin can today be identified with sculptures now at Ickworth, and it is not known how the sculpture returned to the Earls of Bristol from the Hervey Bruce family,to whom the Earl Bishop had left his Irish properties on his death in 1803. Jeremy Warren October 2025

Provenance

Commissioned by Frederic Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol in Rome, c. 1766; 1803, Sir Henry Hervey-Bruce, 1st Baronet of Downhill (died 1822) and by descent; returned at an unknown date to the Hervey family at Ickworth; part of the Bristol Collection. The house and contents were acquired through the National Land Fund and transferred to the National Trust in 1956

Makers and roles

Joseph Nollekens, RA (London 1737 – London 1823), sculptor Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (Rome c.1716 - Rome 1799), sculptor

References

Cavaceppi 1768: Raccolta d'antiche statue busti bassirilievi ed altre sculture restaurate da Bartolomeo Cavaceppi scultore romano, Rome, 1768 The Penny Magazine, 17 July 1841, pp. 277-78. Dublin 1853: Official Catalogue of the Great Industrial Exhibition, Dublin 1853, p. 202, no. 1265, ‘Dolphin and Boy by Raphael’ Manchester 1857: Catalogue of the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom, collected at Manchester in 1857, Manchester 1857, p. 135, no. 89 Scharf 1857: George Scharf, ed. J.B. Waring, Sculpture in Marble, Terra-Cotta, Bronze, Ivory and Wood, London [1857], pp. 36-37 Howard, 1964: Seymour Howard. “Boy on a dolphin: Nollekens and Cavaceppi.” Art Bulletin, 46, No. 2 (June 1964), pp. 177-89, p. 180 Varese 1975: Ranieri Varese, Placchette e bronzi nelle Civiche Collezioni, exh.cat., Palazzo di Marfisa d’Este, Ferrara 1975 Kenworthy-Browne 1979: John Kenworthy-Browne, ‘Joseph Nollekens: the Years in Rome, I. ‘Establishing a Reputation’, II. ‘Genius Recognised’, Country Life, June 7 & 14 1979, pp. 1844-48 & 1930-31 Howard 1990: Seymour Howard, ‘’Boy on a Dolphin: Nollekens and Cavaceppi’ in Antiquity Restored. Essays on the Afterlife of the Antique, Vienna 1990, pp. 78-97, pp.82-84 Bowron and Rishel 2000: E. P. Bowron and J. J. Rishel, eds., Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century, exh cat., Philadelphia Museum of Art, March 16-May 28, 2000 and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, June 25-September 17, 2000, Philadelphia 2000, pp. 269-70, no. 141 Androsov 2008: Sergej Androsov, Museo Statale Ermitage. La scultura italiana dal XIV al XVI secolo, Milan 2008 Roscoe 2009: I. Roscoe, E. Hardy and M. G. Sullivan, A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain 1660-1851, New Haven and Yale 2009, p. 904, no. 146 Bignamini and Hornsby 2010, Ilaria Bignamini and Clare Hornsby, Digging and Dealing in Eighteenth-Century Rome, 2 vols., New Haven/London 2010, I, p. 305