Pair of oval tureens

Frederick Kandler (d.1778)

Category

Silver

Date

1752 - 1753

Materials

Sterling silver

Measurements

35.6 x 44.5 x 27.0 cm (No. 1); 36.2 x 44.5 x 27.9 cm (No. 2)

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852127

Caption

In wealthy households in the 1700s, beautifully designed silver tureens steaming with soup were placed at the head of the table for all the assembled diners to see. In Georgian society, the ostentatious display of silver, far from being considered undignified, was an indicator of wealth, taste and judgement. The contents were usually served by the host and hostess, and the tureens themselves became elaborate status objects that took a starring role in the ritual performance of dining. This one is among the most important pieces of silver in the National Trust’s collections. It was commissioned for Ickworth in Suffolk by George William Hervey, 2nd Earl of Bristol (1721–75), who was a great patron to the most talented silversmiths. It is part of one of the most intact dinner services of this period, and its maker was a German émigré, Frederick Kandler (d.1778), who was adept at interpreting Continental fashions for an English market. Lord Bristol’s coat of arms and the family crest of a chained snow leopard appear prominently on the tureen.

Summary

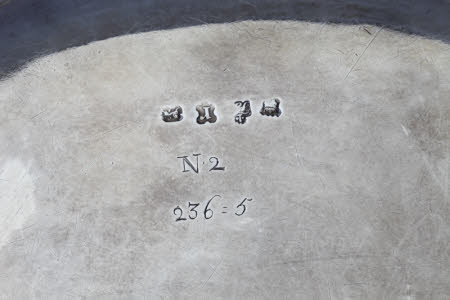

Pair of oval tureens, sterling silver, by Frederick Kandler, London, 1752/3. The shaped oval bombé bases of the tureens each rest on four cast and applied foliate scroll feet, the foliage continuing around the lower edge of the body, intertwining at either end with scroll and rocaille-work that rises around root vegetables to the shell and leaf handles. All this detail is cast and applied as are the coats of arms on either side with asymmetrical shields which rise above shells and have chased mantled backgrounds. Also chased is the lambrequin fringe with repeating oval and flutes and corner floral medallions below a cast and chased reed-and-tie rim. The underside has been cut out of the tureen base around the peripheral scrollwork. The domed cover is shaped to conform to the base with a seamed bezel. Above a simple moulded rim is a chased band of scrollwork around a ribbed lambrequin fringe and with floral medallions at the corners. Another cast reed-and-tie band divides off the tops of the domes which are liberally applied with cast and chased vegetables including artichokes, cabbage, celery, mushrooms, broccoli, cauliflower, parsnips, carrots, bound asparagus, swede and beetroot. The cast handles are in the form of ounces, or snow leopards, ducally collared and chained, each holding a trefoil. The plain oval liners are raised and have rims shaped to fit the bases, applied moulded borders and two cast and applied swan-neck-and-ball handles fixed horizontally. Heraldry: On either side of each tureen is the cast, chased and engraved quartered shield, supporters and motto of the 2nd Earl of Bristol beneath an earl’s coronet and against a chased ermine mantling. The finial handles of the covers are in the form of the Hervey crest. Hallmarks: Each tureen base is fully marked on the outside below the handles with leopard’s head, date letter ‘r’, lion passant and maker’s mark ‘FK’ in italics beneath a fleur-de-lis (Arthur Grimwade, London Goldsmiths 1697-1837, 1990, no. 691). The same set of marks appears on the bases of the liners and on the bezels of the covers. Scratchweights and inscriptions: No. 1: ‘N1 [/] 231=15’ on the base of the liner plus ‘B’ on inside face beneath a handle and on the inside face of the base. No. 2: ‘N2 [/] 236=5’ on the base of the liner plus ‘׀׀’ on inner face by handle ‘A’ at opposite end beneath the handle and ‘A’ on the inside face of the base.

Full description

It is reputed that it was Louis XIV’s love of the Spanish stew called oille that resulted in the appearance of a new and prominent vessel in silver on the late-seventeenth-century French dining table, known as a pot-à-oille.[1] The fashion for soup-like stews spread to England and the Jewel Office issued soup dishes in 1702 and 1703 which must have been reasonably substantial as they weighed 85oz 10 dwt and 73oz 15dwt respectively.[2] In 1704 the Duchess of Marlborough as Groom of the Stole to Queen Anne received a ‘Toureene’ weighing 143oz and there was clearly a distinction between the two vessels which was not just about scale, as three years later the Earl of Sunderland received both a ‘Toureene pott & cover’ of 76oz 5dwt and two ‘soupe Dishes’ with a combined weight of 206oz 5dwt.[3] Perhaps early examples of the latter were merely dishes to serve from whereas the former could also be cooked in, although if so that did not continue to be the case. The word tureen, which was favoured over pot-à-oille in England, is thought to derive from ‘terrine’, the French word which John Kersey in his 1708 dictionary interpreted as ‘an Earthen Pan: In Cookery, a Mess made of a Breast of Mutton, with Quails, Pigeons, &c. stew’d in a Pan.’[4] No very early examples of tureens are thought to survive and though Sir Charles Jackson does refer to one of 1703 by Anthony Nelme being exhibited in 1862, it has since disappeared so its veracity cannot be checked, there being a suspicion that it was a duty dodger with transposed marks.[5] The tureen of 1723 by Paul de Lamerie in the collection of the Duke of Bedford currently stands as the oldest known and it is of the oval, bellied form that was favoured in England up to the late eighteenth century.[6] Another survival from a few years later, of the more German-baroque fluted and sharp-ribbed variety, is by Charles Kandler and bears the mark for 1728.[7] The elder Kandler went on to produce, in 1732, a more fluid and heavily decorated version with a stepped, domed cover for the 2nd Earl of Rockingham.[8] In it can be seen the essence of the Ickworth tureens, mixed up with the spectacular forms coming out of France in the 1730s and 1740s. Numerous aspects of the designs of the Parisian masters of the Rococo, notably Thomas Germain and Jacques Roëttier, emerge in Frederick Kandler’s magnificent creations for the Earl of Bristol. The bands of fluted and ribbed lambrequins, vegetables piled on top, foliate scroll feet and handles, lavish cast ornament around the base, reed and tie borders and the shaped, bombé form all derive from France and are more wholly embraced in the Ickworth tureens than in most other examples of the period. The features can be seen in the engraved designs published by Pierre Germain in his Éléments d’orfèvrerie of 1748 which include the works of Roëttier for the Dauphin.[9] There was quite clearly a familiarity in England well before that too, a related design by Nicholas Sprimont of the early 1740s surviving in the Victoria and Albert Museum [10] and the frontispiece to Vincent La Chapelle’s The modern cook of 1733 showing a similarly embellished circular tureen, probably based on those of the Francophile 4th Earl of Chesterfield whom La Chapelle had served as chef at The Hague. Lord Chesterfield’s liberal table would have been there to inspire other courtiers and their goldsmiths and in 1736 Paul de Lamerie produced a pair almost exactly matching those illustrated by La Chapelle, one of which is now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York.[11] The 4th Earl of Berkeley was amongst those who went further and ordered directly from France, obtaining a full dinner service from Roëttier which is marked for 1735–8 and includes pairs of oval and circular tureens.[12] One element for which French sources were not strong was prominent heraldic display and that was a frequent requirement of British patrons, being a reflection of the greater power of the aristocracy compared with that of absolutist France. Charles Kandler’s 1732 tureen, referred to above, has the lion and griffin supporters of the patron, the Earl of Rockingham, as its feet and handles,[13] one of 1744 by James Shruder has multiple castings of the Legh crest of a ram’s head [14] and the pair of tureens of the same year made by George Wickes to a design by William Kent for the 1st Lord Montfort reflect the supporters of his arms in the horses’ heads holding the drop handles.[15] Many further examples exist on tureens as well as on other significant display items such as epergnes, ewers and basins, fountains and cisterns and even on less prominent tableware. For the Earl of Bristol Kandler did as George Wickes had on a pair of tureens for the Earl of Malton in 1737,[16] casting and applying the arms to make them the centre of attention and forming the handle out of the family crest. His careful integration of these signs of dynastic distinction with the most fashionable of rococo forms resulted in a highly successful end product which must have served its purpose at the increasingly grand gatherings associated with Lord Bristol’s burgeoning career. Of all Lord Bristol’s initial purchases of silver these tureens would have been the most costly, their prominent role as the focus of attention at the commencement of the meal undoubtedly being the spur for such investment. Although only the overall cash payments to Kandler are known, it is likely that the cost per ounce would have been similar to the 13s 7d charged by George Wickes to the Earl of Kildare in 1747 for his tureens and the 13s 6d to the Marquess of Granby for ‘2 Fine Tureens & Covers & Lynings’ in 1750.[17] In the latter case this represented a fashion charge of 8s per ounce, which was about as high as Wickes ever got, and would have been justified by the large amount of one-off casting work required. If such a charge was applied to the Ickworth tureens then the total cost to Lord Bristol, on a combined weight of 468 ounces, would have been £315 18s, a prodigious sum and the equivalent today to at least £42,000.[18] The tureens would have been placed at either end of the table with the two soups that they contained being the first part of the meal to be consumed. Vincent La Chapelle devoted some eighty pages to bisques, pottages, broths and ollios in The Modern Cook, a rather gruesome one to our modern sensibilities being ‘Pottage of a Lamb’s Head’ which was prepared as follows: 'Having scalded your Lamb’s Head and Feet, boil them with the Livers and some midling Bacon in a pot of good Broth; then soak your Crusts, as usual, and place the Heads on them in the soop-dish, garnish it handsomely with Livers and Feet, fry the Brains with the Yolk of an Egg and some crums of Bread, and let them take a fine colour, then put them in their place, and upon the whole throw a white Cullis well tasted, and serve it hot.' The 1st Viscount Jocelyn, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, kept a record of dinners that he gave from 1740 to 1751 and on 1 July 1747, with twelve at table, he served a ‘Crawfish Soop’ and a ‘Soop Loraine’. When done with, these were removed and replaced with a ‘Haunch of Vennison Roast’ and a ‘Chine of Beef’ which would have been served on the largest of the dishes (see NT 852080 and 852095) and carved at the table. A central dish of ‘Broild Mackrall’ made way at the same time for a turkey pie but the sixteen subsidiary dishes remained until the conclusion of the first course.[19] The need to remove the tureens during the progress of the meal probably accounts, along with reducing cost, for the cutting away of unseen silver from the bases of the Ickworth pair. Even so they are unusually heavy because of all the cast work, and would probably have been set on the table before the meal, the liners full of soup being placed in afterwards, immediately before the company entered. For the contemporary ladles associated with these tureens see NT 852078. Dishes to serve as stands were made in Turin in the mid 1750s (see NT 852080 & 852105), as were complementary circular tureens (NT 852128). Exhibited: Treasures from National Trust Houses, Christie’s, London, 1957–8, cat. 172 (one); Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, Florida, 1959 (one); British Week, Milan and Frankfurt, 1965; Silver from National Trust Houses, Treasurer’s House, York Festival, 1969, cat. 36 (one); Treasures from Country Houses of the National Trust and National Trust for Scotland, Europalia 1973, Brussels, cat. 120 (one); The Treasure Houses of Britain, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1985–6, cat. 454. James Rothwell, Decorative Arts Curator February 2021 [Adapted from James Rothwell, Silver for Entertaining: The Ickworth Collection, London 2017, cat. 43, pp. 124-7.] Notes: [1] Marie-France Noël-Waldteuffel, ‘Manger à la cour: alimentation et gastronomie aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles’, in Versailles et les tables royales en Europe XVIIème–XIXème siècles 1993, p. 80, note 11 and Beth Carver Wees, English, Irish & Scottish Silver at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1997, p. 120. [2] The National Archives, LC 9/44, Jewel Office Delivery Book 1698–1732, ff. 65 and 95. [3] Ibid., ff. 95 and 116. [4] John Kersey, Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum: or, a general English dictionary, 1708, unpaginated. [5] Sir Charles Jackson, Illustrated History of English Plate Ecclesiastical and Secular, 2 vols., 1911, p. 816 and Michael Clayton, The Collector’s Dictionary of the Silver and Gold of Great Britain and North America, 1971, p. 267. [6] Clayton 1971 (see note 5), p. 275, plate 43. [7] Cincinnati Art Museum, acc. no. 1982.187. [8] Ellenor Alcorn, English Silver in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Volume II: Silver from 1697, 2000, cat. 74, pp. 130-2. [9] Pierre Germain, Éléments d’orfèvrerie, 1748, notably plates 51 and 76-83. [10] V&A Museum no. E.2606-1917. The design is undated but is thought to be c.1744–5. [11] Metropolitan Museum acc. no. 49.7.99a-d. The pair was sold from the Ortiz-Patiño Collection at Sotheby’s, 4 June 1998, lot 223. [12] Sold Sotheby’s, 16 June 1960 as a single lot. [13] Alcorn 2000 (see note 8), pp. 130-1, ill. [14] Christie’s, 23 November 1999, lot 241. [15] Sotheby’s, 10 November 1994, lot 174. [16] John D. Davis, English Silver at Williamsburg, 1976, cat. 123, pp. 123-4. [17] National Art Library, Garrard Ledgers, VAM 3 1747–50, f. 166. [18] Calculated using the converter on https://www.measuringworth.com. [19] The Winterthur Library, Folio 219, Dinner Book of Robert, 1st Viscount Jocelyn, October 1740 to November 1751, f. 215. .

Provenance

George Hervey, 2nd Earl of Bristol (1721-75); by descent to the 4th Marquess of Bristol (1863-1951); accepted by the Treasury in lieu of death duties in 1956 and transferred to the National Trust.

Credit line

Ickworth, the Bristol Collection (National Trust)

Makers and roles

Frederick Kandler (d.1778), goldsmith

References

Rothwell 2017: James Rothwell, Silver for Entertaining: The Ickworth Collection, London 2017, pp. 124-7