Four sauce boats

Simon Le Sage

Category

Silver

Date

1758 - 1759

Materials

Sterling silver

Measurements

14.9 x 23.2 x 11.4 cm

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852122

Summary

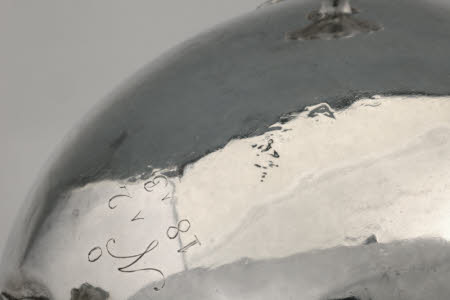

Four sauce boats, sterling silver, by Simon Le Sage, London, 1758/9. The oval bodies are raised and have broad, beak-shaped pouring lips and shaped rims with applied cast gadrooning. Each boat rests on three cast scroll and wavy-shell feet with wavy-shell terminals against the body. The open double-scroll handles with leaf capping are cast. Heraldry: Beneath the pouring lip of each boat are engraved the quartered arms of the Hanoverian monarchs (pre-1801) within the Garter and beneath an imperial crown flanked by the initials G R. Scratchweights: ‘Nº٨1 [/] 18=٨6’; ‘Nº٨2 [/] 18٨3’; ‘Nº٨3 [/] 18٨4’; ‘Nº٨4 [/] 18=10’ Hallmarks: All fully marked on their undersides with date letter ‘C’, leopard’s head, lion passant and maker’s mark ‘S∙L’ in italics with a cup above and mullet below (Arthur Grimwade, London Goldsmiths 1697-1837, London 1990, no. 2576). The marks are all very worn.

Full description

The 1811 plate list [1] reveals that this and the other two types of sauce boat in the collection (NT 852081 & 852082) were each in sets of four, giving a total of twelve available for the dinner table. This was quite a prodigious quantity for the mid eighteenth century, the same as found at Dunham Massey in 1750/54 and two more than in the great Leinster dinner service of 1747.[2] In contrast the decidedly conservative 2nd Duke of Montagu had just four at Montagu House in 1746.[3] The Wickes ledgers and Jewel Office records corroborate a general increase in numbers for the tables of grandees as the century progressed. This is particularly clearly expressed by the case of Henry Bromley, 1st Baron Montfort, of whom Lady Hervey wrote on his unexpected suicide in 1755 that he had ‘a great taste for pleasure and an ample fortune to gratify it’.[4] In February 1743 he turned in eight sauce boats to George Wickes and replaced them with ten and in 1751 the number was upped to twelve.[5] Sauces were critical to fine cuisine in the mid eighteenth century and Vincent La Chapelle in The modern cook, first published in 1733, explains the preparation of over thirty different varieties.[6] They had become increasingly elaborate and extravagant, rumour having it that the Duke of Newcastle’s French chef, Clouet, used a whole ham to make a sauce and twenty-two partridges to produce gravy for a mere brace.[7] William Verral, who had worked with Clouet at Claremont and defended his master against such accusations, included a few more straightforward sauces specifically for sending up in boats in his 1759 publication A complete system of cookery. Amongst these is his (and thus, presumably Clouet’s) version of Sauce Robert: To a ladle of cullis [stock] put a glass of your best white wine, a spoonful of mustard, pepper, salt, shallots and parsley, with plenty of such sorts of herbs as you best approve on; let all stew a minute or two, squeeze in plenty of juice [lemon/orange], and send it up hot in a boat … The reason why the Sauce Robert should not boil long, is, because mustard in boiling grows bitter, and of a nauseous taste.[8] This was one of the most popular models for sauceboats in the 1750s and was produced by numerous different goldsmiths. These ones are rendered superior to many by their finely modelled feet and handles and their well-considered composition. Nos. 1 and 3 have been exposed to greater wear than the others and are dented and worn. James Rothwell, Decorative Arts Curator May 2021 [Adapted from James Rothwell, Silver for Entertaining: The Ickworth Collection, London 2017, cat. 65, p. 150] Notes: [1] Suffolk Record Office, 941/75/1, list of plate belonging to the 5th Earl and 1st Marquess of Bristol, 1811-40. [2] James Lomax and James Rothwell, Country House Silver from Dunham Massey, 2006, pp. 53 & 167, and Elaine Barr, George Wickes, 1980, p. 198. [3] Tessa Murdoch, Noble Households: Eighteenth Century Inventories of Great English Houses, 2006, p. 109. [4] J. W. Croker (ed.), Letters of Mary Lepel, Lady Hervey, 1821, pp. 206-7. [5] National Art Library, Garrard Ledgers, VAM 2 1740-8, f. 86 and VAM 5 1750-4, f. 12. [6] Vincent La Chapelle, The Modern Cook, 1733, pp. 94-104. [7] Barbara Ketcham Wheaton, Savoring the Past, 1983, pp. 166 and 204-5. [8] William Verral, A complete system of cookery, 1759, pp. xxx-i and 233-4. Exhibited: British Week, Milan and Frankfurt, 1965.

Provenance

Jewel Office; allocated to George Hervey, 2nd Earl of Bristol (1721-75) as Ambassador to Madrid 1758; discharged to Lord Bristol 9 April 1759; by descent to the 4th Marquess of Bristol (1863-1951); accepted by the Treasury in lieu of death duties in 1956 and transferred to the National Trust.

Credit line

Ickworth, the Bristol Collection (National Trust)

Makers and roles

Simon Le Sage, goldsmith