Four round dishes with covers and four smaller dishes

Frederick Kandler

Category

Silver

Date

circa 1751 - circa 1758

Materials

Silver

Measurements

2.2 x 32.4 cm (dishes); 18.4 cm x 27 cm (covers); 2.5 x 27.3 cm (small dishes)

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852121

Summary

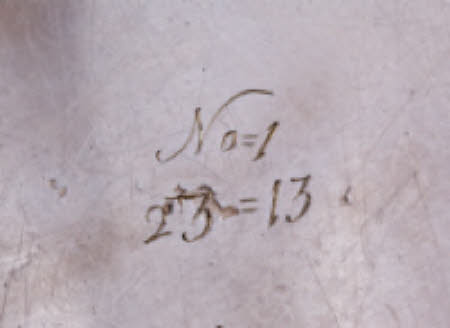

Four round dishes, silver, probably by Frederick Kandler, London, circa 1751 (NT 852121.3.1-4); four round covers for the dishes, silver, probably London, circa 1758 (NT 852121.1.1-4); and four small round dishes, sterling silver, by Frederick Kandler, London, 1754/5 (NT 852121.2.1-4). All the dishes are raised with shallow circular wells, broad rims and cast shaped borders with twelve gadrooned lobes each having a central acanthus leaf. At four of the intersections between the lobes are cast scallop shells with pearl bands and flanking foliate scrolls. The four round and lobed covers are raised and have stepped bases conforming to the larger dishes (NT 852121.3.1-4). The bases terminate in a chased band of gadrooning and the covers rise as circular convex domes to another chased gadroon band, then rise again in reverse form to an applied flat top plate, the joint concealed by a cast and seemed moulding. The cast and chased tendril handles are capped by single flowers and held on by silver bolts and nuts. Heraldry: The rims of the dishes are engraved with the quartered shield, supporters and motto of the 2nd Earl of Bristol in an ermine mantling and beneath an earl’s coronet. The reverse of dish no. 1 also has the wreath of a crest from the old vessel turned in. On the front of each cover are engraved the quartered arms of the Hanoverian monarchs (pre-1801) within the Garter and beneath an imperial crown flanked by the initials G R. Hallmarks: Dishes - There are no marks on these dishes contemporary with their making. Two are unmarked and two retain the marks on their undersides of the old pieces that were altered c.1751. Dish no. 1 has the maker’s mark ‘BO’ beneath a mitre and above a cross (Arthur Grimwade, London Goldsmiths 1697-1837, 1990, no. 201) for John Bodington, lion’s head erased, Britannia and date letter ‘R’ for 1712. Dish no. 2 has, distorted by the re-working, the maker’s mark ‘CR’ beneath a pair of mullets and above a fleur-de-lis (Grimwade 1990, no. 406) for Paul Crespin. Covers – None. Small dishes - The dishes are fully marked on the underside of their rims with the lion passant, date letter ‘t’, maker’s mark ‘FK’ in italics beneath a fleur-de-lis (Grimwade 1990, no. 691) and leopard’s head. Scratchweights: Dishes - ‘N1 [/] 32=19’, ‘N 2 [/] 34=2’, ‘No 3 = 34=14’ and ‘Nº 4 [/] 34=15’ Covers - ‘Nº- 1 = 33=0’; ‘No 2 = 35=0’; ‘No 3 = 34=3’; ‘No 4 = 34=6’ Small dishes - ‘No=1 [/] 23=13’, ‘No=2 [/] 24=3’, ‘No=3 [/] 24=5’ and ‘No=4 [/] 24=10’

Full description

DISHES As with Ickworth’s large oval dishes (NT 852080), sauce boats (NT 852082) and salad dishes (NT 852062), these dishes have cast shells to unite them with the rest of the service. The borders, which are particularly finely modelled, derive from those which emerged in the mid 1740s and were most spectacularly employed on the Leinster dinner service supplied by George Wickes in 1747, though in that case combined with reeding rather than gadrooning.[1] From the evidence of the hallmarks (two without any and two with those of former pieces) and scratchweights, plus slight differences in the engraving of the arms, these four dishes represent the combination of two separate sets, so there may well have been eight originally, supplied in two batches. Although often referred to as ‘second course dishes’ such a term seems only rarely to have been applied in the mid eighteenth century [2] and they would have been able to be used with the first, second or third courses, all of which needed subsidiary dishes, or hors d’oeuvres, on the table around the principal fare.[3] Hors d’oeuvres were described by Louis Liger in his 1711 publication, Les ménage des champs et le jardinier françois as being served ‘aux trois premiers services’ [4] and examples given by Vincent La Chapelle in 1736 for ‘a Supper of 15 or 16 Covers’ included ‘Mutton-Cutlets glaz’d with Endive’, ‘Larks the Moscovite way’ and ‘Fillets of Soles with Champain’.[5] As with the London-made plates (NT 852124), scientific analysis has confirmed that the body of the dish sampled (no. 1) is Britannia standard and the border sterling.[6] This piece also has an old setting-out mark well off the current centre which suggests a previous existence as a much larger dish. The 1st Earl does not record any silver purchases in 1712–13, the date of the hallmark, but that year does coincide with both Carr Hervey’s return from three years abroad and his coming of age, so the dish could have been his. Alternatively it could have formed part of the plate acquired from the estate of Lady Howard of Effingham in 1727,[7] as might the surviving salver by Robert Cooper, made the same year and subsequently owned by the Hon. Felton Hervey.[8] Unlike the handles on the smaller oval dishes at Ickworth, the prominent shells on the borders of the smaller round dishes (NT 852121.2.1-4) have not been scaled down from the larger set (NT 852121.3.1-4) though the gadrooning has been. They are the smallest of all the dishes and might have been used for hors d’oeuvres or for some of the light entremets [9] placed instead of salads and sauces for the third course. On Vincent La Chapelle’s ‘Bill of Fare for a Supper of 15 or 16 Covers’ these included cock’s combs, green peas, duck’s tongues and eggs with gravy. The small round dishes are much worn and were evidently heavily used by the Herveys up to 1951. COVERS The Jewel Office allocation in 1758 lists twenty dish covers as being delivered for Lord Bristol’s use in 1758 and of these only the eight now at Ickworth survive.[10] The absent twelve, which had gone by 1811,[11] are unlikely to have been part of the scheme to extract money for the excessive fashion cost of other items (see NT 852077) as they would have had to be specifically made for the dishes and to have matched the covers that do survive. Thus they could not easily have been taken from stock and then passed on to other clients once they had served their illicit purpose. They must therefore have been exchanged or lost at some point thereafter, or have been removed to Ireland by the Earl-Bishop and passed to the Bruce family. As they would have had to account for 935 ounces of silver they would have been for the larger sizes of dishes. The covers would have been in place at the start of the meal and have been removed when the tureens were taken away to be replaced with the next set of principal dishes. In the painting of the coronation banquet of Joseph II as King of the Romans in Frankfurt in 1764,[12] all the subsidiary tables are shown with their dishes still covered whereas at the high table the Imperial couple have commenced their meal and two attendants are removing the covers and passing them to footmen. As dishes did not rest on the table in the same fashion for service à la russe the need for covers waned during the nineteenth century and many must have been turned in to be melted, making them rare today. They did still come into their own at breakfast, however, and one can be seen in use at Ickworth alongside dishes by Paul Storr in a photograph of c.1870. Silver dish-covers were never commonplace in the aristocratic household anyway and many families had some or all of them in silvered brass or copper, or even as mere pewter. William Strode, for instance, acquired a ‘Brass Dish Cover Silver’d’ from Wickes and Netherton in 1753 for £2 including engraving (the same thing in silver, assuming a weight of 30 oz., would have cost at least £12) and the vastly wealthy Sir Jacob Downing, 4th Bt, when equipping himself with a dinner service in 1750, had seventeen pewter covers with his twenty silver dishes.[13] Lord Bristol may well have been thus equipped previously and have used the opportunity of the ambassadorial allocation to upgrade. For the contemporary octagonal dishes and covers see NT 852115. James Rothwell, Decorative Arts Curator February 2021 [Adapted from James Rothwell, Silver for Entertaining: The Ickworth Collection, London 2017, cat. 36, 49 & 73, pp. 117, 133 & 160-1.] Notes: [1] Elaine Barr, George Wickes, 1980, pp. 197-205, ill. [2] Three dishes of 1759 at Temple Newsam by William Reynolds or Reynoldson have been inscribed ‘2nd course’ on their undersides, probably contemporaneously. See James Lomax, British Silver at Temple Newsam and Lotherton Hall, 1992, cat. 85, pp. 94-5. I am grateful to the author for alerting me to this example. [3] Barbara Ketcham Wheaton, Savoring the Past, 1983, p. 140. [4] Marie-France Noël-Waldteuffel, ‘Manger à la cour: alimentation et gastronomie aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles’, in Versailles et les tables royales en Europe XVIIème–XIXème siècles (Paris, 1993), p. 76. [5] Vincent La Chapelle, The Modern Cook, 1736, vol. 1, plate VII. [6] X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis carried out March 2015 on dish no. 1. The body is 96.94% silver and the border 95.71%. [7] Suffolk Record Office, 941/46/13, 1st Earl of Bristol’s diary and accounts 1688-1742. [8] Sotheby’s, 4 March 1965, lot 169. [9] Entremets from old French means ‘between courses’. See Margaret Visser, The Rituals of Dinner, 1991, pp. 200-1. [10] The National Archives, LC 9/48, Jewel Office Accounts and Receipts Book 1728-67, ff. 166-8. [11] Suffolk Record Office, 941/75/1, list of plate of the 5th Earl (later 1st Marquess) of Bristol 1811-29. [12] Studio of Martin II Mytens, Schloss Schönbrunn, Austria. [13] National Art Library, Garrard Ledgers, VAM 5 1750–4, f. 110 and VAM 3 1747-50, f. 57.

Provenance

Dishes: George Hervey, 2nd Earl of Bristol (1721-75); by descent to the 4th Marquess of Bristol (1863-1951); accepted by the Treasury in lieu of death duties in 1956 and transferred to the National Trust. Dish covers: Jewel Office; allocated to George Hervey, 2nd Earl of Bristol (1721-75) as Ambassador to Madrid 1758; discharged to Lord Bristol 9 April 1759; by descent to the 4th Marquess of Bristol (1863-1951); accepted by the Treasury in lieu of death duties in 1956 and transferred to the National Trust.

Credit line

Ickworth, the Bristol Collection (National Trust)

Makers and roles

Frederick Kandler, goldsmith