Sauce boat

Edward Feline (fl.1720)

Category

Silver

Date

1751 - 1752

Materials

Sterling silver

Measurements

10.8 x 20.6 x 10.2 cm

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852081

Summary

Sauce boat, sterling silver, by Edward Feline, London, 1751/2. The oval sauce boat is raised with a cast gadrooned and shaped border and four cast lion’s paw and acanthus leaf feet. A cast Neptune mask is applied beneath the lip and the scroll handle, which is cast in two equal parts, is in the form of a stylised dolphin, its head resting on a cast leaf-and-scroll fitment applied to the body of the boat. The condition is poor, the sauce boat evidently having been the subject of regular use. Heraldry: Both sides are engraved with the quartered shield, supporters and motto of the 2nd Earl of Bristol in an ermine mantling and beneath an earl’s coronet. The engraving is very worn.

Full description

The 1811 plate list [1] reveals that this and the other two types of sauce boat in the collection (NT 852082 & 852122) were each in sets of four, giving a total of twelve available for the dinner table. This was quite a prodigious quantity for the mid eighteenth century, the same as found at Dunham Massey in 1750/54 and two more than in the great Leinster dinner service of 1747.[2] In contrast the decidedly conservative 2nd Duke of Montagu had just four at Montagu House in 1746.[3] The Wickes ledgers and Jewel Office records corroborate a general increase in numbers for the tables of grandees as the century progressed. This is particularly clearly expressed by the case of Henry Bromley, 1st Baron Montfort, of whom Lady Hervey wrote on his unexpected suicide in 1755 that he had ‘a great taste for pleasure and an ample fortune to gratify it’.[4] In February 1743 he turned in eight sauce boats to George Wickes and replaced them with ten and in 1751 the number was upped to twelve.[5] Sauces were critical to fine cuisine in the mid eighteenth century and Vincent La Chapelle in The modern cook, first published in 1733, explains the preparation of over thirty different varieties.[6] They had become increasingly elaborate and extravagant, rumour having it that the Duke of Newcastle’s French chef, Clouet, used a whole ham to make a sauce and twenty-two partridges to produce gravy for a mere brace.[7] William Verral, who had worked with Clouet at Claremont and defended his master against such accusations, included a few more straightforward sauces specifically for sending up in boats in his 1759 publication A complete system of cookery. Amongst these is his (and thus, presumably Clouet’s) version of Sauce Robert: 'To a ladle of cullis [stock] put a glass of your best white wine, a spoonful of mustard, pepper, salt, shallots and parsley, with plenty of such sorts of herbs as you best approve on; let all stew a minute or two, squeeze in plenty of juice [lemon/orange], and send it up hot in a boat … The reason why the Sauce Robert should not boil long, is, because mustard in boiling grows bitter, and of a nauseous taste.'[8] Of the set of four associated with the Feline sauce boat at Ickworth, one is noted as having been ‘lost’ in the copy plate list of 1874 [9] and the other two were retained by the family before being sold by the 7th Marquess in 1996.[10] One of those is also by Feline whilst the second bears marks for John Jacob and 1738, suggesting that there were originally pairs by each. The Jacob boats are likely to have been supplied to Lord Hervey by Paul Crespin (see cat. 18) and the dolphin handle and Neptune mask are consistent with the 1730s and with plate from the Lamerie/Crespin circle. The knuckled dolphin handle is of seventeenth-century auricular inspiration and was, with its allusion to water, particularly appropriate for vessels intended for liquids.[11] It is thus far first recorded in 1719 on a cream ewer by David Willaume I,[12] which also exhibits a cast mask beneath the lip, and it has a strong association thereafter with de Lamerie. Examples are found by him on several pairs and groups of sauce boats with conch-shell bodies made between 1729 and 1738, many also with Neptune masks.[13] The Jacob sauce boat and pairs by Aymé Videau and Paul Crespin, both of 1735,[14] suggest that the mould was being used by several silversmiths and it was very probably still available for Feline in 1751.[15] If the shaped, gadrooned rim on the Jacob sauce boat is contemporary then it is an exceptionally early example.[16] It could be, however, that Feline re-shaped a simple, wavy rim, which would have been more typical for the time, and applied the gadrooning before copying that adapted form to create the set of four. Why Lord Bristol chose not to have all eight in the same pattern, and added yet another type in 1758, is an interesting question. It is probably partly answered by his desire to concentrate the cost of fashion where it would really count and in this and many of the other elements of his dinner service the Earl does not seem to have minded a harlequin effect, provided there were even sets that could be placed symmetrically. Indeed, the variety thereby created may even have been seen as a positive advantage in the age of riotous movement and distortion that was the Rococo. James Rothwell, Decorative Arts Curator February 2021 [Adapted from James Rothwell, Silver for Entertaining: The Ickworth Collection, London 2017, cat. 29, pp. 107-8.] Notes: [1] Suffolk Record Office, 941/75/1, list of plate belonging to the 5th Earl and 1st Marquess of Bristol, 1811-40. [2] James Lomax and James Rothwell, Country House Silver from Dunham Massey, 2006, pp. 53 & 167, and Elaine Barr, George Wickes, 1980, p. 198. [3] Tessa Murdoch, Noble Households: Eighteenth Century Inventories of Great English Houses, 2006, p. 109. [4] J. W. Croker (ed.), Letters of Mary Lepel, Lady Hervey, 1821, pp. 206-7. [5] National Art Library, Garrard Ledgers, VAM 2 1740-8, f. 86 and VAM 5 1750-4, f. 12. [6] Vincent La Chapelle, The Modern Cook, 1733, pp. 94-104. [7] Barbara Ketcham Wheaton, Savoring the Past, 1983, pp. 166 and 204-5. [8] William Verral, A complete system of cookery, 1759, pp. xxx-i and 233-4. [9] Suffolk Record Office, 941/75/3, Bristol copy plate list 1874. [10] They were offered first by Sotheby’s, 9 November 1995, lot 299, but must have failed to sell as they were offered again at Sotheby’s Suffolk, 11–12 June 1996, East Wing Ickworth, lot 344b (not in catalogue) when they sold for £2,500. They are now in a private collection. [11] For a discussion of the Van Vianen source of this feature and its use by different silversmiths see Christopher Hartop, The Huguenot Leagacy: English Silver 1680-1760, 1996, cat. 30, pp. 175-7, Ellenor M. Alcorn, English Silver in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, vol. II, 2006, cat. 18, pp. 71-2 and Timothy Schroder, British and Continental Gold and Silver in the Ashmolean Museum, 2009, cat. 153, pp. 396-7. [12] Beth Carver Wees, English, Irish and Scottish Silver at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1997, cat. 253, pp. 365-6 [13] Sotheby’s, 11 November 1993, lot 462 (1729), Alcorn 2006 (see note 11), cat. 18, pp. 71-2 (1730), Christie’s, 16 June 1965, lot 36 (1734) and Hartop 1996 (see note 11), p. 176, ill. (1738). [14] Sotheby’s, 27 June 1963 and Hartop 1996 (see note 11), cat. 32, pp. 182-3. [15] Timothy Schroder has pointed out that two not quite identical moulds were in use amongst silversmiths in the 1730s and 1740s. See Schroder 2009 (see note 11), pp. 396-7. [16] The first mention of a ‘knurl’d’ or gadrooned sauce boat in the Wickes ledgers is in 1744, National Art Library, Garrard Ledgers, VAM 2 1740–8, f. 53, Sir John Chapman, 15 December 1744, and one of the earliest surviving examples, with a shaped rim, is found on a pair of double-lipped sauceboats of 1741 by Peter Archambo in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. See Hartop 1996 (see note 11), cat. 41, pp. 206-7.

Provenance

George Hervey, 2nd Earl of Bristol (1721-75); by descent to the 4th Marquess of Bristol (1863-51); accepted by the Treasury in lieu of death duties in 1956 and transferred to the National Trust.

Credit line

Ickworth, the Bristol Collection (National Trust)

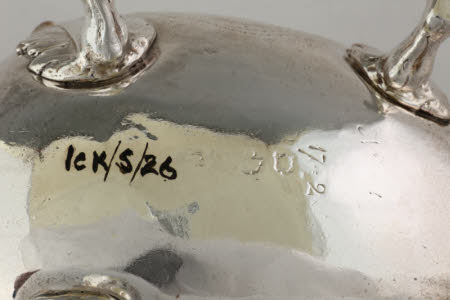

Marks and inscriptions

Underside: Hallmarks (very worn): lion passant, date letter ‘q’, maker’s mark ‘EF’ in italics beneath a pellet (Arthur Grimwade, London Goldsmiths 1697-1837, 1990, no. 587) and leopard’s head. Underside: Scratchweight: ‘Nº 1 [/] 17=2’

Makers and roles

Edward Feline (fl.1720), goldsmith