Four dessert baskets

Paul de Lamerie (1688 - 1751) and Frederick Kandler (d.1778).

Category

Silver

Date

1731 - 1732

Materials

Silver

Measurements

8.6 x 34.9 x 27.0 cm

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852063

Summary

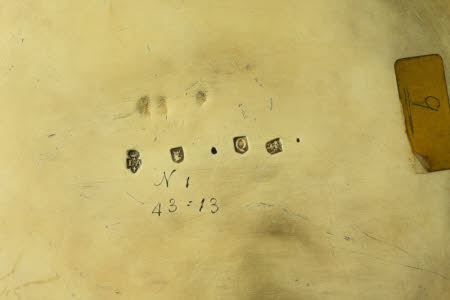

Four dessert baskets, silver-gilt: one Britannia silver, originally ungilded and made as a bread basket, by Paul de Lamerie, London, 1731/2; another Sterling silver, originally ungilded and made to match as a bread basket, by Frederick Kandler, London, 1752/3, and two more made to match as dessert baskets, Sterling silver, gilded, by Frederick Kandler, London, 1768/9. The body of each basket has been raised from a single sheet to form an oval with a flat base, slightly angled sides and flared rim. The sides and rim are pierced in a graded diaper pattern and chased inside and out to resemble plaited willow-cane basketwork. A corded wire is soldered to the outer edge of the rim. At the angle between the rim and the sides, on the inside face, is a reed-and-tie moulding surmounted by a narrow corded wire. These are soldered against a plain, unpierced band of the body, presumably left to provide strength. The rising loop handles are constructed of three thick wires twisted together with narrow corded wires and terminating in the form of tendrils soldered to the body of the basket at the narrow ends. The rim foot is made up of a seamed strip pierced with interlocking open ovals and bounded by reed-and-tie mouldings. The floor of the basket is engraved in a late Régence style with trelliswork, shells, scrolls and straps, the outer band being hatched to imply shading. Heraldry: The centre of the floor of each basket is engraved with the quartered shield, supporters and motto of the 2nd Earl of Bristol within an ermine mantling and beneath an earl’s coronet. Hallmarks: No.1 - Fully marked on the underside with maker’s mark ‘LA’ star and closed crown above fleur-de-lis below (third mark, unregistered – see Susan Hare (ed.), Paul de Lamerie, At the Sign of the Golden Ball, 1990, p. 29), lion’s head erased, Britannia and date letter ‘Q’. No. 2 - Fully marked on the underside with maker’s mark ‘FK’ in italics beneath a fleur-de-lis (Arthur Grimwade, London Goldsmiths 1697-1837, 1990, no. 691), leopard’s head, lion passant and date letter ‘r’. Nos. 3 & 4 - Each fully marked on the underside with date letter ‘N’, leopard’s head, lion passant and maker’s mark ‘FK’ in italics beneath a fleur-de-lis (Grimwade 1990, no. 692). Scratchweights: ‘N1 43=13’; ‘N 2 [/] 43=17’; ‘No 3 [/] 45=11’; ‘No-4 [/] 45=14’.

Full description

Baskets for the service of bread would have resided on the sideboard and been brought to the table by a footman, the handles allowing the contents to be offered with stability and elegance, as well as with ease of access for the diners. An analysis of the Jewel Office records suggests that they began to be fashionable in silver from the early 1720s, being issued both in pairs and individually.[1] The earliest of these was a pair granted in 1723 as part of his perquisite plate (for an explanation of perquisite plate see chapter 3) to the Hon. Spencer Compton, Speaker of the House of Commons. With a combined weight of just over 204 ounces, each of the Compton baskets would have been around 100 ounces, and as the other four supplied up to 1732 were in the same league the group may well have been of a broadly standard form.[2] Fortunately one at least is known to survive: that granted to the 1st Duke of Dorset as Lord Steward of the Household in 1725.[3] It is by Thomas Farren and is circular with diaper piercing, a chased, spreading foot, a flared rim and a cast and fixed pail handle. This form appears to be an adaptation of the earliest English silver baskets of a comparable size to survive, those of 1597 and 1641 which both bear London marks.[4] They lack carrying handles and are thought to have been intended for fruit which had become fashionable as part of the dessert.[5] The transition of silver baskets from fruit to bread is strikingly illustrated by the plate lists of the Dukes of Montagu. In 1706 two baskets for lemons and one for fruit are recorded, lemons and fruit are again specified in 1709 but in 1733 the only one of the three remaining is described as a ‘Bread or Lemon Basket’.[6] Furthermore, the reference to fruit may only have been retained in this instance because of previous recordings and the distinct form of the piece, and all other examples of a comparable scale in the Jewel Office records and the Wickes ledgers, up to the mid century, are described as bread baskets.[7] The upright, circular form of the Farren and Elizabethan examples was not exclusive and the Ickworth basket derives from the other principal strain in which natural willow basketwork was accurately mimicked in the pierced and chased sides. This went to the extent of replicating the three canes of willow gathered together in each strap, as still commonly practised today in basketwork.[8] The earliest English examples known to survive are two baskets by John Eckford of 1703 and they in turn are comparable to a pair made in Paris in 1657, perhaps suggesting that the form derives from mid-seventeenth-century France, though the paucity of survivals prevents any definitive conclusions being drawn.[9] David Willaume I produced a circular version in 1723 with somewhat clumsy basketwork, and the following year saw a more accomplished rendering, also circular, by Paul de Lamerie.[10] There were numerous subsequent versions, almost exclusively oval, by different makers over the next thirty years, but the pronounced peak occurred in 1731 and the great majority of those produced that year, including the Ickworth basket, bear Lamerie’s mark. Even amongst these there are variances: some, for instance, have single, pail handles, others pairs of twisted wire handles, and the basketwork is either rigidly laid out in a perfect diaper or follows a more relaxed, naturalistic pattern with graduated and attenuated lozenges. The latter, which more effectively sustains the illusion, must have been the more difficult to achieve and is the pattern adopted for both the Ickworth basket and its closest comparator from that year, which bears the arms of Sir Robert Walpole and is now in the Gilbert Collection at the V&A.[11] It, though, is half an inch higher and considerably heavier, at 57 oz. 6 dwt. Unlike the baskets of the mid 1720s, which have plain, polished bases around central armorials, Lamerie’s baskets, and those of some other makers, exhibit lavish late-Régence detail, veering towards the rococo, which almost completely fills the field: space is just left for the owner’s arms. The Ickworth and Walpole models are, once again, near-identical and given that Lord Hervey was becoming increasingly intimate with Walpole at this time, having thrown in his lot with the administration in 1730 and been appointed Vice-Chamberlain of the Royal Household, it is tempting to see a link. Hervey certainly dined with the First Lord of the Treasury at this time and could well have been inspired by the sight of the new and superbly crafted basket.[12] It is evident anyway from the number of baskets of a comparable form produced in such a short period that the fashion for them spread very rapidly, and being seen at the table of the most powerful subject in the country could only have helped. Much attention has been given to the hand of Lamerie’s engraver, who exhibits particular prowess, and both William Hogarth and his master, Ellis Gamble, have previously been suggested. It has now been convincingly argued by Timothy Schroder, however, that it was neither. He has identified a group of engraved plate, including several of these baskets, which has evidence of the same authorship and, in the absence of a name, he has dubbed him the ‘Hasell engraver’ after the family who acquired a number of the pieces.[13] The evidence of contemporary plate lists, the Wickes ledgers and the Jewel Office records, together with the fact that silver for the main courses of dinner was almost without exception white, make it highly probable that the Ickworth basket was ungilded when it was acquired. Given its date the first owner could have been either the 1st Earl of Bristol or Lord Hervey, but such a highly fashionable acquisition would seem more likely for the son than the father, particularly given Hervey’s intimate connection with both the Court and the Walpole administration. The original armorials do not survive and nor do Lord Hervey’s accounts but his father’s are more comprehensive and they corroborate that he was not the purchaser. Lord Hervey had been accumulating a dinner service over the previous decade and with his additional income of £600 as Vice-Chamberlain he would have been in a good position to continue doing so into the 1730s. Assuming the basket was Lord Hervey’s it would have been inherited on his death in 1743 by his eldest son, George. Following his succession as 2nd Earl in 1751 it would have been sent with the bulk of the family plate to Frederick Kandler to be refashioned and ‘done up as new’, as George Wickes termed a comprehensive overhaul of old pieces that were to be retained. Given that the basket was of a form still being produced and was intricately decorated, the fact that it was not at the cutting edge of fashion must have been outweighed in Lord Bristol’s mind by the considerable monetary saving. A wholly new piece would have cost at least 3 shillings an ounce for fashion, amounting to over £6, whereas ‘doing up’ might have been as little as 10 shillings, if needed at all.[14] The Earl’s ambition was such, however, that he required a prodigious dinner service, and though a single bread basket might have been adequate in a great household in his grandfather’s day, it was so no longer. Lord Bristol thus commissioned a copy from Kandler, which bears the date letter for 1752. It too would have been supplied without gilding and the pair probably stayed in that state for another sixteen years. The addition of two more bread baskets in 1754 (NT 852109), marked by John Robinson and in an entirely different and quite simple fashion, may well have been for everyday use, but in 1768 a further pair of copies of the Lamerie basket was commissioned from Kandler and it was probably at this point that the complete set of four was gilded and turned over to use as dessert baskets.[15] From the mid 1750s baskets specifically for fruit re-emerged, though never in large numbers. The Countess of Pomfret received two from Wickes and Netherton in 1755 and the Countess of Mountrath one, gilded, in 1757.[16] Lord Bristol’s provision was lavish and may have been occasioned by the introduction of the mirror plateau (NT 852091). With that in place in the centre of the table, it would not have been possible to accommodate the epergne, with its multiple baskets for fruit, and an alternative would thus have been needed. The names of those who executed the raising, piercing, chasing and engraving of the three copies of the original basket by de Lamerie are not known but they were clearly highly skilled, attaining an almost exact match to the earlier work. It is only in the minute detail of execution that differences can be discerned. In addition to the saving in cost, the fine and profuse nature of the late Régence decoration, coupled with the suitability of feigned basketwork for the Rococo, must have persuaded Lord Bristol to keep the earlier basket and copy it rather than commissioning a new pair in 1752 or a new set in 1768. James Rothwell, Decorative Arts Curator January 2021 [Adapted from James Rothwell, Silver for Entertaining: The Ickworth Collection, London 2017, cat. 19, 45 & 86, pp. 95-7, 129 & 175] Notes: [1] The National Archives, LC 9/44, Jewel Office delivery book, 1698–1732. [2] Ibid., fos. 218, 264, 271, 286 & 300. The Compton pair weighed 182 oz 10 dwt to which 21 oz 18 dwt were added, perhaps in the form of handles. Three of the others were around 94 oz and the fourth was 77 oz. [3] Christopher Hartop, The Huguenot Legacy: English Silver 1680-1760, 1996, cat. 7, pp. 94-7. It passed by descent with Knole in Kent until being sold at Christie’s, London, 20 May 1987, lot 172. [4] The 1597 basket was sold at Christie’s, London, 25 November 2008, Lot 53. The 1641 basket is in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, acc. no. 68.141.60. [5] Philippa Glanville, Silver in Tudor and Early Stuart England, 1990, p. 220; Michèle Bimbenet-Privat and David Mitchell, ‘Words or Images: descriptions of plate in England and France 1660-1700’, The Silver Society Journal, no. 15 (2003), pp. 50-51 [6] Northamptonshire Record Office, Montagu Papers, MH2, ‘An Acct. of the Plate’, 21 November 1706, and MH 6, ‘His Grace the late Duke of Montague’s Plate Weighed and Valued by Geo. Lewis’, 28 March 1709. The 1733 inventory of Montagu House, including plate, is included in Tessa Murdoch, Noble Households, 2006, pp. 27-48. As the 1709 plate list indicates that of the two baskets then present the one for lemons was ‘Old Sterling’ and that for fruit ‘New’, or Britannia, the latter must be that by George Lewis, c.1700, now in the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown (see Beth Carver Wees, English, Irish & Scottish Silver in the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1997, cat. 99, pp. 179-81) and have been the sole survivor in 1733. [7] The National Archives, LC 9/44 & 9/45, Jewel Office delivery books, 1698–1732 and 1732–93. National Art Library, Garrard Ledgers 1735–54, VAM 1-5. [8] See for instance the products of The Bengal Basket Company, http://www.bengalbasket.co.in/willow-basket-2586440.html. [9] John Eckford baskets: Sotheby’s, London 10 July 1990, lot 399 and Christie’s 12 June 2002, lot 112. These are silver-gilt but are not likely to have been gilded when supplied. French baskets, 1657: Christie’s, Geneva, 13 May 1981, lot 159. [10] David Willaume basket: Christie’s, London, 6 March 1991, lot 136. Lamerie 1724 baskets: one of the pair, Christie’s, New York, 22 April 1998, lot 6, the other, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Acc. No. 68.16.1. [11] Timothy Schroder, The Gilbert Collection of Gold and Silver, 1988, cat. no. 49, pp. 200-3 and Christopher Hartop, ‘Sir Robert Walpole’s Silver’, Silver Studies, no. 29 (2013), pp. 40-41. [12] Robert Halsband, Lord Hervey: Eighteenth century courtier, 1973, pp. 94-7. [13] Timothy Schroder, British and Continental Gold and Silver in the Ashmolean Museum, 2009, pp. 216-7 and 666-9. [14] National Art Library, Garrard Ledgers, 1735–54, VAM 1-5. The new baskets recorded up to 1740 range from 9s. to 10s. per oz., excepting that for the Prince of Wales billed on 1 May 1736 at just under 11s. 5d. per ounce. The metal was being charged at between 5s. 6d. and 6s. per ounce, thus fashion was at least 3s. [15] Sir Benjamin Keene, Lord Bristol’s predecessor as ambassador at Madrid, made a distinction between his wrought plate for dining in state and that of plain form ‘for every day’s use.’ Sir Richard Lodge (ed.), The Private Correspondence of Sir Benjamin Keene, 1935, p. 240. [16] National Art Library, Garrard ledgers, VAM 5 1750–4, f. 224 and VAM 6 1756–60, f. 115.

Provenance

No. 1, of 1731/2 by Paul de Lamerie, was probably commissioned by John, Lord Hervey; Nos. 2-4, of 1754/5 and 1768/9 by Frederick Kandler, were commissioned by the 2nd Earl of Bristol; by descent to the 4th Marquess of Bristol; accepted by the Treasury in lieu of death duties in 1956 and transferred to the National Trust.

Credit line

Ickworth, the Bristol Collection (National Trust)

Makers and roles

Paul de Lamerie (1688 - 1751) and Frederick Kandler (d.1778)., goldsmiths Paul de Lamerie (1688 - London 1751) , goldsmith Frederick Kandler, goldsmith