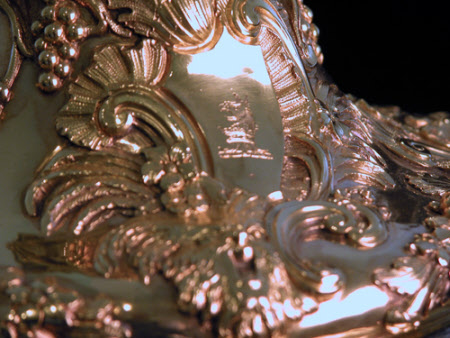

Cup and cover

Peter Taylor

Category

Silver

Date

1746 - 1747

Materials

Silver-gilt, sterling

Measurements

42.2 x 36.4 cm; 30.2 cm (Height); 24.7 cm (Height); 17.4 cm (Width); 14.2 cm (Width); 19.0 cm (Height); 18.9 cm (Diameter); 4760 g (Weight)

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Anglesey Abbey, Cambridgeshire

NT 516444

Summary

A two-handled cup and cover, silver-gilt (sterling), mark of Peter Taylor, London, 1746/7. The baluster-shaped cup and its cover are raised and applied with finely detailed cast and chased rococo decoration. The circular spreading foot is cast and decorated with grapes, vine leaves, snakes and applied lizards. The cast calyx of shells and scrolls is soldered to the foot with a reinforcing ring visible inside the foot. The body is decorated with a riot of ornament including shells, scrolls, festoons of flowers, garlands of vine leaves and grapes, heads of Bacchus, squirrels, bird’s wings, ladybirds, asymmetric shields engraved with a coat of arms, and, standing in high relief, cast lizards and flies. The finely modelled flying handles are cast and chased with borders of rocaille-work and scales, topped by vine leaves and bunches of grapes, and applied with a cast fly and lizard. Each handle terminates in a detailed goat’s head, whilst the lower end attaches to the cup with a monstrous snarling monkey-like head. The cover has a reeded rim, beneath which is an applied flange. The steeply rising sides are applied with lions’ masks, grotesque heads, scrolls, flowers, berries, vine leaves, grapes, ladybirds, flies, foliage and two rococo cartouches engraved with a crest. The cast finial is formed as a bacchic cherub eating grapes whilst seated on a mound of leaves applied with a lizard and fly. Rivets, which were used to secure the cast elements to the metal, are visible inside both the cup and its cover; both of which have been later gilded. Heraldry: The arms on the body of the cup are those of WATSON quartering MONSON with a crescent as mark of cadency for a second son, impaling PELHAM quartering PELHAM ancient for the Hon Lewis Watson (later 1st Baron Sondes) (1728-1795) and his wife Grace (1728-1777), daughter of the Rt Hon Henry Pelham (Prime Minister 1743-54). The crest on the cover is that of WATSON. Hallmarks: Fully marked on the base of the cup within the foot ring and on the flange of the cover: lion passant (sterling), leopard’s head (London), ‘l’ (1746/7) and ‘PT’ (Peter Taylor*) * Arthur Grimwade: London Goldsmiths 1697-1837, 1990, p 162, no 2239 Scratch weight: None

Full description

NOTES ON THE STYLE OF THE CUP The cup and cover are decorated with an extraordinary exuberance of finely modelled rococo ornament. Peter Taylor trained as a silversmith, but it is presumed that in this instance he acted as a retailer. The question arises as to the identity of the highly skilled silversmith in whose workshop the piece was made. Possible candidates must include Frederick Kandler, Paul de Lamerie, Louis Pantin I, George Wickes, and Thomas Heming, all of whom were masters of this style of applied ornament. Kandler and de Lamerie both used rivets as well as solder to secure their decoration, as seen here, and there are examples of similar cups made by them which also have highly modelled bunches of grapes, applied cast insects and bacchic cherub finials; whilst the shape of the cover is seen on cups marked by Wickes. There is evidence that 18th century goldsmiths shared their moulds or bought their cast ornaments from the same modellers. This makes identifying the maker of this cup impossible, although Kandler is probably the strongest contender. Stylistically similar cups include: 1. A silver-gilt two-handled cup and cover with the same finial, unmarked, but attributed to Paul de Lamerie, which has been identified as appearing in the ledgers of George Wickes, goldsmith to the Prince of Wales: ‘24 January 1740 a fine chased gilt cup and cover £61 3s’. See: Elaine Barr, George Wickes; Royal Goldsmith 1698-1761, 1980, pp 161–62, pl 102; and Royal Collection number: RCIN51016 2. A silver-gilt cup and cover, London, 1742/3, mark of Paul de Lamerie. See: Timothy Schroder, The Gilbert Collection of Gold and Silver, 1988, object no 67, pp 260-64 3. A silver-gilt cup and cover, London, 1749/50, mark of Frederick Kandler. See: Tessa Murdoch (ed), Boughton House, The English Versailles, 1992, pl 91 4. A silver cup and cover, London, 1749/50, mark of Frederick Kandler. See: St Louis Art Museum website, Acquisition Number 252:1952a,b, https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/630/ 5. A silver cup and cover, London, 1744/5, mark of Louis Pantin I. See: Anglesey Abbey, National Trust Inventory Number 516498 6. A set of three silver cups and covers, the largest with a similar finial, London, 1752/3, mark of Thomas Heming. See: Christie’s sale: Bayreuth: A Connoisseur’s Collection of English Silver and Gold Boxes, London, 7 July 2023, lot 105 7. A silver-gilt cup and cover, with similar finial, mark of Thomas Heming, London, 1759/60. See Victoria & albert Museum: acquisition number: M.41:1,2-1959 Arthur Grimwade wrote that ‘although rare, his work when found shows a high standard of craftsmanship coupled with a nice use of rococo ornament’. The sugar box and pair of tea caddies marked for Peter Taylor in 1747/8, now in the museum of Fine Arts, Boston, demonstrate this with their exquisitely chased sides decorated with elaborate architectural follies and figures in exotic dress. [1] Christie’s sold a set of four cauldron-shaped salt cellars, marked by Taylor a year earlier. Whilst the shape of these is common, their decoration is not. The sides are decorated with extraordinary swags of shells and leaves suspended from auricular masks within rocaille borders. [2] [1] Ellenor Alcorn: English Silver in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Volume II, Boston, 2000, pp 166-167 [2] Christie’s, New York; Living with Art, 14 June 2017, lot 399 NOTES ON PETER TAYLOR Peter Taylor (1714–1777) was the second son of Robert Taylor, a grocer of Wells. In 1728 he was apprenticed to Charles Lewis, a goldsmith of Wincanton, Somerset. [3] Taylor’s only maker’s mark was entered on 11 November 1740, as a largeworker. Heal records him as a ‘plate-worker: Golden Cup, against Southampton Street, or corner of Cecil Court, Strand 1740-1753’. [4] A Parliamentary Report in 1773 mentions a ‘Peter Taylor, goldsmith, Strand’. However, there is little extant silver with his hallmark. This is not surprising given that he spent most of his adult working life as a British administrator and politician. In 1757, at the outbreak of the Seven Years War, he was appointed Deputy Paymaster in Germany where he spent five years. He was at times dealing with £150,000 a month and questions were raised about his conduct. He returned to England in 1763 with a poor reputation but in possession of a large fortune which he used to buy an estate at Burcott, near Wells, and another at Purbrook Park, near Portsmouth where he built a mansion designed by Sir Robert Taylor (unrelated). Having achieved great wealth, Taylor wanted to crown his success with a seat in Parliament. He was Member of Parliament for Wells for less than a month, and then Portsmouth for three years, however, there is no record of his having spoken in the House or done anything to help his constituency. Whilst his reputation is tarnished, silver bearing his hallmarks is of exceptional quality, often with finely modelled rococo ornament. [3] Society of Genealogists: Country Apprentices 1710–1808 [4] Ambrose Heal: The London Goldsmiths 1200-1800, Newton Abbott, 1972 reprint, p 253 HERALDRY The Monson family was part of the Whig hegemony of the mid-eighteenth century who established a strong power base after the accession of George I in 1714. The Hon. Lewis Watson, formerly Monson (1728-95), of Rockingham Castle, co. Northants, and of Lees Court, Kent, was the second son of John, 1st Baron Monson of Burton by Margaret, fourth and youngest daughter of Lewis (Watson) 1st Earl of Rockingham. He took the name of Watson in lieu of his patronymic Monson in February 1745/46 upon the death of his first cousin Thomas Watson, 3rd and last Earl of Rockingham, when he succeeded to the Rockingham estates. In 1752 he married his third cousin Grace Pelham (1728-77).Watson was eighteen when he inherited; he was in Italy on his Grand Tour in 1749 and came of age in November that year. Whilst abroad Watson was returned by Newcastle for the seat of Boroughbridge, which he represented until 1754; he was subsequently MP for Kent 1754-60. On 4 October 1750 the Duke of Newcastle reported from Hanover to Henry Pelham (the Prime Minister) that he had just had ‘a very mortifying slight’. He had arranged to present Watson, Malton, Pelham, Lord Downe and three other young Englishmen of quality on their travels [to George II then in Hanover]. ‘I acquainted H.M. with it beforehand. He flew out - “what did they come there to trouble him for?” I answered, to show their zeal and attachment. “Let them show it in Parliament” etc. When they were presented in the circle, before all the foreign ministers and all the court, H.M. said not one word to anyone, but a little to Lord Malton, and a little, very little, to Lord Downe. I fear the effect of this unhappy incident.’ In 1754 his father-in-law procured Watson the life sinecure of Auditor of the Imprest (an Exchequer office) which was abolished by Act of Parliament in 1785 subject to the payment to him of £7,000 a year ‘in lieu of the profits and emoluments of the said office’ until his death. Watson aspired to the House of Lords: Newcastle was ultimately successful in pressing his claim with George II when in 1760 Watson was created Baron Sondes of Lees Court, co. Kent. The coat of arms on the cup dates between Watson’s marriage in 1752 and his elevation to the peerage in 1760. Jane Ewart, 2025 Heraldry by Gale Glynn ADDITIONAL INFORMATION BY JAMES ROTHWELL When the 1st Earl of Rockingham (1655-1724) died he bequeathed his estates to his eldest grandson the 2nd Earl (c. 1714-45, his father had died in 1721/22), and most unusually bequeathed his plate to his daughter Margaret (1695-1751), who had married John, 1st Baron Monson (c.1693–1748).[1] In his will Lord Monson specified that his widow should receive ‘... so many Ounces of my plate as shall be Chosen by herself as shall be equal to the number of Ounces of plate that belonged to her at the time of our Marriage and which was settled to her own Seperate use by a certain deed or Instrument in Writing which said plate hath been since Changed and disposed of ...’.[2] On Lady Monson’s death it is most likely that the plate, (which, because it was ‘exchanged’ would not have had a direct connection to her own Watson family) went to her eldest son, the 2nd Lord Monson. Her second son Lewis had by then inherited Lord Rockingham’s large estates; he was left only £100 by his father as a token of affection ‘on account of the Great provision that has already been made for him’.[3] The 2nd Earl of Rockingham (who was styled Viscount Sondes 1722-24), evidently succeeded to a respectable quantity of plate on the death of his father (who presumably had been provided for by the 1st Earl, perhaps on his marriage in 1708), and he also inherited his mother’s plate.[4] This is detailed in a list entitled ‘Account of Old Plain Plate belonging to The Earl of Rockingham [2nd Earl] when he was Ld. Sondes 1736’.[5] The striking out and date are later additions and relate to subsequent alterations to the list. The description of ‘plain’ would accord with the fashion prevailing under Queen Anne. When the 2nd Earl died he too left the family plate away from the male line, bequeathing it instead to his wife Catherine Furnese[6] from whom it then passed to her second husband.[7] The 2nd Earl’s brother, the 3rd Earl (1715-46), thus appears to have inherited no family plate and, as he only survived his brother by less than three months, he would scarcely have had time to commission much. Lewis Watson would have needed to make up for the dearth of plate in his inheritance. It would make absolute sense if the cup and cover bearing the marks of Peter Taylor 1746/7 was part of such new acquisitions, to be engraved subsequently following his marriage. Evidence from the ledgers of George Wickes and his successors is that inheritors of estates regularly made acquisitions, and refurbished and remodelled plate, within a remarkably short period of inheriting, and that was generally in the context of a sizeable quantity of existing plate which Watson clearly lacked.[8] Alternatively, the cup may have been acquired in celebration of his marriage in 1752 or in 1754, the year he acquired the sinecure and his son was born. It would not have been unusual to purchase an object six or eight years after it had been made: the cup might have remained in Taylor’s stock, or have been second-hand. A pair of square waiters, Paul Crespin 1736/7 (now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), have the same arms as those on the cup. They appear in a plate list drawn up in 1806 following the death of Lewis, 2nd Lord Sondes (1754-1806)[9] as ‘4 Square, Handwaiters 92[oz] 9[dwt] [10] and in a plate list of 1830 as ‘4 7½ in Square Waiters / Figurd’.[11] The cup and cover is not included in the 1806 inventory; ‘5 Cups Gilt 167[oz] 7[dwt]’ listed therein are specified in more detail in a valuation carried out by Rundell, Bridge & Co. following the death of the 3rd Lord Sondes in 1836:[12] 2 small gilt 2 handle Cups & Covers (plain) } 62[oz] 5[dwt] A Gilt large plain 2 handle Cup & Cover } 75[oz] 10[dwt] 2 Less do. do. } 29[oz] 5[dwt] The Taylor cup could not possibly have been described as ‘plain’ and its weight, at 153 troy oz (4760 gr), far exceeds even the largest of those recorded in 1836. It is possible that the rococo Taylor cup was traded in, perhaps through Rundell or Garrard, in exchange for a suite of five classical-style cups - the weight differential between the five cups together and the Taylor cup is about 13oz. The condition of the engraving suggests either that the cup has avoided excessive polishing or, bearing in mind that its whereabouts are unrecorded throughout the nineteenth century and until its acquisition by Lord Fairhaven, that the engraving might have been ‘refreshed’, even as late as the twentieth century. 1 The National Archives (henceforth TNA), PROB 11/597/186, proved 9 May 1724. 2 TNA, PROB 11/764/60, proved 5 August 1748. 3 Ibid. 4 TNA, PROB 11/664/92, proved 5 March 1734. 5 Kent Archives, Waldershare Park Manuscripts, EK/U471/A56: Kitchen accounts [2 weeks only] (1736-42), Servants' wages; inventory of china at Waldershare and of plate belonging to the Earl of Rockingham. 6 TNA, PROB 11/743/485, proved 24 December 1745. Catherine was the daughter of Sir Robert Furnese 2nd Bt., of Waldershare Park in Kent, which she had inherited as co-heiress. There is a fascinating series of accounts of her plate amongst the Waldershare Park Manuscripts, detailing its moves to and from London between 1747 and 1752, including what was left behind. This plate, with her estates and the London house in Grosvenor Square built by the Earl of Rockingham, passed to her second husband Francis North, 1st Earl of Guildford (1704-90) on her death in 1766. 7 TNA, PROB 11/925/258, proved 27 January 1767. 8 James Rothwell, Silver for Entertaining: The Ickworth Collection, 2017, p. 116. 9 Kent Archives, Sondes Manuscripts, U791/E125, Executorship papers of Lewis Richard Lord Sondes (d. 1836): ‘An Inventory & Appraisement of the Household Furniture, Plate, Linen & c, of the Rt. Honble Lord Sondes, taken on the Premises, the 4th Day of July, 1806 and Following Days.’ 10 Ibid: ‘An Inventory & Appraisement of the Household Furniture, Plate, Linen & c, of the Rt. Honble Lord Sondes, taken on the Premises, the 4th Day of July, 1806 and Following Days.’ 11 Ibid: ‘An Inventory of Plate at Lees Court Belonging to the Right Honble Lord Sondes’ ‘Taken June 9th 1830’. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/481984, inspected 24 May 2023; and Christopher Hartop, The Huguenot Legacy: English Silver 1680-1760 from the Alan and Simone Hartman Collection, 1996, cat. 93, pp. 362-3 (ill.). No date of sale from the Sondes collection is given for these waiters in the museum’s online catalogue or in the printed catalogue of the Hartman Collection. 12 (as note 9): ‘A Valuation of Jewels, Plate &c for The Executors of the late Right Honble Lord Sondes. By Rundell Bridge & Co. 29th March 1836’.

Provenance

The Hon Lewis Watson (later 1st Baron Sondes) (1728-1795) (Urban) Huttleston Rogers Broughton, 1st Baron Fairhaven (1896-1966) bequeathed by Lord Fairhaven to the National Trust along with the house and the rest of the contents. National Trust

Credit line

Anglesey Abbey, the Fairhaven Collection (National Trust)

Makers and roles

Peter Taylor, goldsmith

References

Ellis, 1999: Myrtle Ellis. 'Huttleston Broughton, 1st Lord Fairhaven (1896-1966) as a collector of English silver.' Apollo, 1999