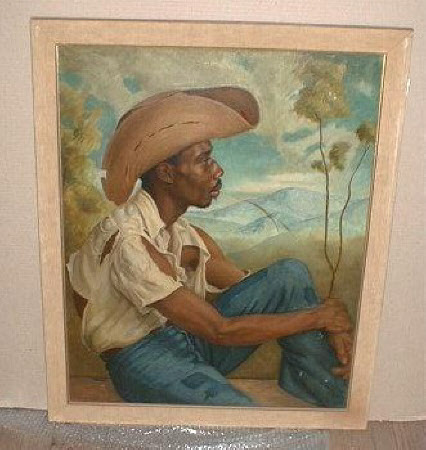

Seated Man in a Landscape

James Richmond Barthé (Bay St Louis 1901 - Pasadena 1989)

Category

Art / Oil paintings

Date

c. 1950 - 1958

Materials

Oil on canvas

Measurements

853 x 695 x 25 mm

Place of origin

Jamaica

Order this imageCollection

Belton House, Lincolnshire

NT 436186

Summary

Oil painting on canvas, Seated Man in a Landscape, by James Richmond Barthé (Bay St. Louis, Mississippi 1901 - Pasadena, California 1989), c. 1950-58, signed bottom left Barthé. A three-quarter-length portrait of a seated man in profile, looking right, with a blade of grass between his lips. The sitter wears a large straw hat, a torn white shirt, and patched jeans. With trees, hills and mountains in the distance, against a blue sky with large white clouds.

Full description

James Richmond Barthé is best known as a figurative sculptor who explored through the potential of the human body ideas of spiritualty, sexuality and race. He generally but not exclusively portrayed black subjects, particularly the black male nude. In this, one of the artist’s few surviving oils, Barthé returned to his original medium of painting. The portrait was painted in Jamaica in the mid-20th century and is one of Barthé’s only known oils in a British public collection. Formative years Born in 1901 at Bay St Louis, Mississippi, James Richmond Barthé was the only son of Richmond Barthé and Marie Clementine (Clémente) Raboteau. An early aptitude for drawing was fostered in adolescence during work as a domestic helper in a wealthy New Orleans household. There, Barthé made copies after pictures and sculpture in the family’s collection, and after paintings in a personal folio of old master reproductions (Vendryes 2008, p. 21). In 1924 he gave his first finished oil painting to his local Catholic church, and from this the seeds of a formal artistic training were planted (ibid). The congregation raised enough money for Barthé to take two terms at an art school. Then, the only institutions accepting black students were the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago – he was accepted by the latter (Vendryes 2008, p. 22). Anatomical drawing classes at Chicago led to the Barthé’s first experiments in clay modelling. Showing considerable talent, his academic course shifted towards the plastic arts. His first exhibition of pictures and sculpture was held at the Chicago Women’s Club in the Autumn of 1927, after which he received a first paid sculptural commission and was able to enrol as a full-time student. In 1929, upon graduating, Barthé moved to New York City and there became closely associated with leading figures in the Harlem Renaissance, notably Alain Locke (1885-1954), who bought his work and helped him to navigate the contemporary art scene and its patronage networks. It was to Locke, a gay man, that Barthé also spoke of his own homosexuality. Over the next two decades Barthé became a widely exhibited, critically acclaimed sculptor. He won several high-profile public commissions, and received prestigious fellowships from the Guggenheim and Rosenwald Foundations. Together with paintings by Jacob Lawrence, his bronzes were the first works by an African American artist to enter the permanent collections of the Whitney and Met museums (see, for example, Blackberry Woman, 1932, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, acc.no. 32.71 and Boxer, 1942, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acc. no. 42.180). Jamaica In 1949 Barthé left New York for Jamaica, where he would live until 1969. At this point in his career the artist had become disillusioned with sculpture and with the politics and scrutiny of the art world. He imagined a new creative life in Jamaica, in which he could refashion himself exclusively as a painter. Barthé purchased a house – which he named Iolaus – in a remote part of St Ann parish, on the north coast of the island. The reality of the artist’s Jamaican experience was complex and at times troubled. A celebrated sculptor in New York, Barthé’s geographic separation from the mainland United States was professionally isolating. His social circles reduced to part-time expatriates. The local Jamaican community associated Barthé with these largely white upper-class groups and their suspicions about his sexual orientation alienated him further (Vendryes 2020). Of this marginal status he wrote to a friend: ‘I do hope that you and your family will love your adopted country and that your adopted country will adopt you […] This is what I had dreamed of happening to me in Jamaica. I expected it because I loved Jamaica, but unfortunately, my people here have never accepted me. After over twenty years, I am still being called a foreigner.’ (Barthé to Canon LB Harrison, 6 July 1968, quoted in Vendryes 2008, p. 176) Barthé suffered recurrent bouts of creative inertia, as his paintings failed to gain much critical acknowledgement, as well as chronic episodes of mental and physical ill-health. He kept an open studio at Iolaus and generated income by selling sculptures to visiting expatriates and tourists. According to anecdote he routinely gave away paintings, or whitewashed them (Vendryes 2008, p. 163). Barthé inevitably returned to sculpture, but nonetheless maintained a two-dimensional practice. Indeed, a solo exhibition of drawings and paintings, mostly portraying rural Jamaicans, held at the Institute of Jamaica in 1958, secured his representation at the Hills Gallery, a contemporary art gallery in Kingston (ibid). A year later, amidst the mounting Civil Rights and Jamaican Independence movements, he would model one of his most powerful and overtly political sculptures to date, the Awakening of Africa (see acc.no. LOK 2005.5.1, Cook Library Art Gallery, University of Southern Mississippi). Seated Man A small housekeeping staff cared for Barthé at Iolaus. Among them was Lucian Levers, a young man who became the artist’s principal model and the subject of several pastels, oil paintings and sculptures. Levers can be identified as the sitter in the present portrait based on a photograph taken in 1959 of the young man, accompanied by Barthé, posing beside his sculpted bust (reproduced in Vendryes 2008, p. 167, fig. 5.21). In this portrait Levers is posed against a painted backdrop of a romanticised rural scene in Jamaica, with the Blue Mountains in the distance. He is possibly in the guise of an agricultural worker, his torn short-sleeved shirt revealing Levers’ lean musculature beneath. A pastel portrait of circa 1953 shows Levers assuming another role, this time cloaked in white in the character of Othello (reproduced in Vendryes 2008, p. 160, fig. 5.15). Exactly how this painting came to be at Belton is unknown, but it is likely to have been acquired by Peregrine Cust, 6th Baron Brownlow (1899-1978) who kept a holiday home in Jamaica (see NT 436318, an album containing photographs of the family there in the 1950s). The Brownlows may have been known Barthé socially or may have bought or been given the painting at the artist’s studio. The portrait is signed but bears no gallery label, unlike the watercolours by the Jamaican artist Leonard Morris (b. 1931) at Belton, which were acquired from the Hills Gallery in Kingston (NT 436260).

Provenance

Probably acquired by Peregrine Cust, 6th Baron Brownlow (1899-1978) in Jamaica; purchased with a grant from the National Heritage Memorial Fund (NHMF) from Edward John Peregrine Cust, 7th Baron Brownlow, C. St J. (b.1936) in 1984.

Credit line

Belton House, The Brownlow Collection (acquired with the help of the National Heritage Memorial Fund by the National Trust in 1984)

Marks and inscriptions

Bottom left: Barthé

Makers and roles

James Richmond Barthé (Bay St Louis 1901 - Pasadena 1989), artist

References

Vendryes 2008: Margaret Rose Vendryes, with foreword by Jeffrey C. Stewart, Barthé, A Life in Sculpture, Mississippi 2008 Vendryes 2011: Margaret Rose Vendryes, ‘Young, Gifted, and Black Between the Wars - Richmond Barthé's Manhattan Years’, Sculpture Review: A Publication of the National Sculpture Society, vol. LX, no. 3, Spring 2011