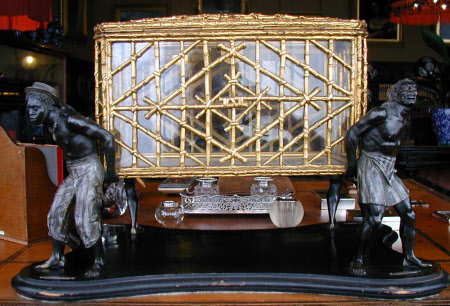

Casket with personifications of Virginia, Maryland, Havana, and Brazil

Category

Art / Sculpture

Date

c. 1855 - 1865

Materials

Gilt metal, bronzed metal, glass, ebonised wood

Measurements

370 x 585 x 387 mm

Order this imageCollection

Cragside, Northumberland

NT 1228296

Summary

Gilt and bronzed metal, glass, ebonised wood, a casket, British or French, c. 1855-65. A glazed lidded casket, the glass encased in gilt metal sugarcane latticework, the casket supported by bronzed metal figures representing Virginia, Maryland, Havana, and Brazil. The figures are male, probably enslaved plantation workers of African heritage. They stand facing away from the casket with their hands clasped behind their backs each lifting a corner of the casket. The figures bear the load on the smalls of their backs, their upper bodies stooped forwards. The men are bare chested and wear shorts, cropped trousers, and loincloths, all made of the same striped linen; two wear headwraps, and one a straw boater hat and a beaded necklace. Each figure with a silver metal label engraved respectively ‘Maryland’, ‘Virginia’, ‘Havannah [sic]’, ‘Brazil’, affixed to the base. Mounted on an ebonised base. The casket is first recorded in 1881, when it was illustrated in an image of Sir William Armstrong in his study.

Full description

A large bronze casket supported at the corners by personifications of Brazil, Havana, Maryland and Virginia. The casket is lidded, with lid and body formed from a gilt-bronze latticework in the form of lengths of sugar cane bound together, with a series of vertical stems, a single horizontal row and diagonally-placed stems, producing a form of diamond pattern on each side. The casket is supported by four men clearly intended to represent slaves, each personifying a major centre of the tobacco and sugar industries, as identified by a silver label between their feet: Brazil, Havana, Maryland and Virginia. ‘Brazil’ wears a loin cloth and a striped cloth wrapped around his head; ‘Havannah’, wearing a striped apron around his waist and bandanna around his head, looks upwards to his right; ’Maryland’ is depicted wearing a straw hat and long striped trousers, and around his neck is a necklace with a pendant; ‘Virginia’ wears striped shorts and turns his head sharply to his left. The figures are made of bronze, patinated, and with the clothes coloured. The figures stand upon an ebonised wood base, curved at the corners and with concave sides. The casket is first recorded in 1881, when it appeared in an illustration in the 2 April 1881 issue of the newspaper 'The Graphic', accompanying an article on the installation of Swan electric lighting at Cragside. The casket is depicted on a table near the window in the study of Sir William Armstrong, who is shown seated at his desk reading. It is not known when or how Armstrong acquired the object, but it could well have been one of the many gifts he received from customers of and suppliers to his businesses. Maryland and Virginia were among the first colonies of English North America, and the locus of the Chesapeake tobacco industry servicing Europe since the 17th century. While British tobacco imports were temporarily disrupted by the American Revolution, after the conflict the demand and profitability of tobacco boomed, with many colonial planters using British credit to expand their land and slaveholdings. The major trading city of Havana, until 1898 within the colony of Spanish Cuba, was briefly occupied by the British between 1762 and 1763. Enslaved African labour was brought to Cuba and Portuguese Brazil in the 16th century, primarily to support the sugarcane industries. During their tenure the British imported approximately 4,000 enslaved Africans to expand the Cuban plantation system. Over five million enslaved people were brought from Africa to colonial Brazil, more than any other country involved in the Atlantic slave trade. Together, Cuba and Brazil were Britain’s principal rivals in the trades of sugar and tobacco. The casket reflects the time period known as ‘Second Slavery’, which dated from around 1790, reached its height around the middle of the nineteenth century and came to a final end in 1888, with the abolition of slavery in Brazil. The term refers to the fact that by the early nineteenth century the ‘First Slavery’ period, initiated and driven by the British and other European colonial powers, was drawing to an end with moves towards abolition, but the practice of slavery nevertheless persisted throughout much of the Americas, supporting the production of cotton and tobacco in the southern United States, sugar in Cuba and coffee in Brazil. With its identification of four major centres of nineteenth-century slave labour, which however produced very different products, the casket may be seen as a form of allegorical representation of the Second Slavery period. It is very likely that it was produced before 1864-65, when slavery was abolished in Maryland and Virginia. The casket is the sort of imposing object that might well have been exhibited at one of the international exhibitions held in Europe around the middle of the nineteenth century, such as the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, the Universal Exhibition held in Paris in 1855 and the London International Exhibition of 1862. It has not however proved possible to trace it in any of the illustrated surveys published to accompany these events. Although it is highly sculptural, the casket would no doubt have been treated as an example of applied arts and so would have drawn less attention than, say, traditional sculptures such as John Bell’s 'Daughter of Eve', also at Cragside (NT 1228372). The most individual elements of the casket are the well-modelled supporting figures which represent individuals naturalistically and without stereotyping. They echo the Quattro Mori, four over-life size bronze figures of African and Arab captives placed around the statue of the Tuscan Grand Duke Ferdinando I on the monument made by Pietro Tacca (1577-1640), in the first half of the seventeenth century, for the Tuscan port of Livorno (Leghorn), a centre for the Mediterranean slave trade that flourished as a consequence of the long-term running conflict between the Christian and Ottoman powers in the Mediterranean basin. Pietro Tacca’s figures are in fact captives, chained prisoners in a form of representation that is first seen in Roman art, and as such somewhat different to the figures in the Cragside casket, who are shown bearing the heavy burden of the large container, which may also have been intended to store one of the products produced using slave labour in the Americas. It has often been described as a large box for cigars, but this is unlikely to have been its use during the lifetime of Sir William Armstrong, who was not a smoker (Henrietta Heald, 'William Armstrong. Magician of the North', Newcastle upon Tyne 2010, pp. 177-78). There are also strong parallels with the ‘ethnographic’ sculpture of the French sculptor Charles Cordier (1827-1905), who specialised in portraits of individuals from non-European cultures, and whose ethnographically highly accurate portraits of Africans and Asians often incorporated coloured marbles, coloured bronze patinas and the addition of elements such as jewellery, to create a decorative and romanticised vision of foreign peoples that was designed to meet the expectations of Western audiences (Laure de Margerie and Edward Papet, eds., 'Facing the Other. Charles Cordier (1827-1905), Ethnographic Sculptor', New York 2004). Cordier’s work was known and admired in Britain. Examples of two of Cordier’s major works, the bronze busts of an African man and woman known as 'Saïd Abdullah' ('Saïd Abdallah, de la Tribu de Mayac, Royaume de Darfour' ) and the ‘African Venus’ ('Vénus africaine') were exhibited in the 1851 Great Exhibition, and a pair was bought by Queen Victoria for Osborne House in 1852 (Jonathan Marsden (ed.), 'Victoria and Albert. Art and Love', exh. cat. Queen’s Gallery, London 2010, pp. 156-57, nos. 87-88). In 1861 Cordier held a major selling exhibition in London entitled the 'Ethnographical Gallery of Sculpture by Mr. Cordier' illustrating the most prominent types of the human race, with sculptures of Europeans and non-Europeans, whilst at the 1862 exhibition in London, versions of two more of his most iconic works were exhibited, the so-called 'Capresse des Colonies' and 'Nègre du Soudan'(Margerie and Papet, cats. 70-71). It would seem likely that the casket was made in Britain or perhaps France, by someone with quite good knowledge of the work of Charles Cordier. Sir William Armstrong (1810–1900) was a Newcastle upon Tyne-born industrialist, designer and manufacturer of arms. His work led to his knighthood in 1859 and his simultaneous appointment as government engineer for rifled ordnance and superintendent of the royal gun factory at Woolwich. During the four years he was working directly with the government, it placed over £1 million worth of orders for Armstrong breech-loading guns. The arms were used by British military forces in conflicts across the globe. This is one of three objects at Cragside that were owned by Sir William Armstrong and that explicitly refer to the practice of slavery and the arguments for abolition that grew ever stronger in Britain from the second half of the eighteenth century onwards. The others are a column inlaid with a Wedgwood 'Slave Medallion' (NT 1230999) and John Bell’s 'Daughter of Eve'. Whereas both those works of art clearly carry an anti-slavery message, this does not seem to be the case with the casket, although neither is it self-evident that the object was made with the intention of celebrating the practice. Little evidence to date has been found in Armstrong’s own writings concerning his personal views on slavery, but a long passage in his book 'A Visit to Egypt in 1872', published in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1874 and based on lectures he gave there after he had travelled to Egypt to advise the Khedive on bridging the cataracts of the Nile, suggests he was strongly opposed to the practice. Armstrong wrote that domestic slavery was technically illegal in Egypt but was widely practised, commenting that these domestic slaves were in practice often well-treated in the households in which they worked, but that “The manner in which the poor creatures are kidnapped is atrocious, and is by far the worst part of the business. There are gangs of ruffians on the White Nile who do this horrible work, and their mode of proceeding is to make incursions into adjacent lands, and there, surrounding the villages, they set fire to everything that will burn. When the people rush out of their houses, the men are shot down, the children captured, and the women left to starve or provide for themselves.” He went on to criticise the system of forced common labour in Egypt, suggesting that “The evils and injustices of this system are fully recognised by the Khedive and his government. I heard one of his most able and enlightened ministers denounce it as horrible, but then, he added, it is at present a necessity; without it, labour could not be procured for the maintenance of the canals and the great irrigation works upon which the very existence of Egypt depends” (A Visit to Egypt in 1872, pp. 30-33; Heald, William Armstrong, pp. 176-77). It has been asserted that as a leading armaments manufacturer, Sir William Armstrong turned a bliond eye to the selling of his company’s products to both sides in the American Civil War. The Union sought to acquire guns through a complex scheme involving subterfuge (Marshall J. Bastable, 'Arms and the State. Sir William Armstrong and the remaking of British Naval Power, 1854-1914', Aldershot 2004, pp. 126-28; Heald, William Armstrong, pp. 109-10), but these were never delivered, and recent research has demonstrated conclusively that Armstrong did not supply either side (Henrietta Heald, personal communication). A letter of 21 January 1864 to The Times from the Elswick Ordnance Company, in response to allegations that a cargo destined for the Confederate government included Armstrong guns, stated that ‘no Armstrong guns made by us, or under our authority, have yet been shipped to any foreign Government whatever.’ Alice Rylance-Watson and Jeremy Warren March 2022

Provenance

Acquired by Sir William Armstrong before 1881; Armstrong collection; transferred by the Treasury to The National Trust in 1977 via the National Land Fund, aided by 3rd Baron Armstrong of Bamburgh and Cragside (1919 - 1987).

References

'Electric Lighting by the Swan System at Sir William Armstrong's residence, Cragside', The Graphic, 2 April 1881, p. 332 Beach 2016: Caitlin Beach, 'John Bell’s American Slave in the Context of Production and Patronage', Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Summer 2016) Stable, pp. 12-14, figs. 12-14.