Cabinet on stand

Category

Furniture

Date

1670 - 1690

Materials

Tortoiseshell, gilt brass, ebony and bone and ebonised beech on oak and deal construction

Measurements

118 x 175 x 51 cm

Place of origin

Antwerp

Order this imageCollection

Oxburgh Hall, Norfolk

NT 1209805

Caption

An Antwerp cabinet was a luxury item in the 17th-century, used to display curiosities and to impress guests. This fine example may have been at Oxburgh since it was made, or could be another of Sir Henry Paston-Bedingfeld, 6th Baronet’s Continental acquisitions.

Summary

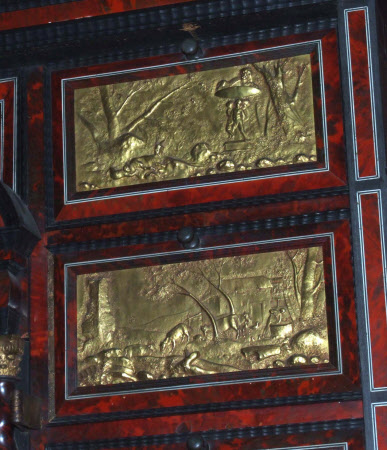

An ebony, tortoiseshell, bone, gilt brass and rosewood cabinet on stand, Antwerp, circa 1680. With some alterations to the stand. The cabinet with a rectangular top with a narrow molded edge above an arrangement of fourteen drawers around a pair of paneled cupboard doors. The ten flanking small drawers applied with gilt brass repousse panels each decorated with landscape scenes with figures, animals and trees. The central top drawer with a shaped repousse panel decorated with putti and scrolling ribbons and swags flanked by two female figures seated upon quarter circular moldings. the lower drawer of breakfront form with further conforming landscape panels. The pair of cupboard doors with arched repousse panels depicting woodland scenes which are flanked by twist turned half columns and gilt brass ionic capitals. The doors opening to reveal a mirrored architectural interior with chequered floor centered by an octagonal panel inlaid with an eight pointed star. The mirror panels interspaced with classical painted scenes and with gilt beech twist turned columns. Flanking the mirrored recess are a pair of removable panels each fronted as four small drawers, the panels lift out to reveal four hidden drawers and below the recess a further long drawer fronted as three short drawers. The base of the cabinet has two further narrow drawers. The stand with molded edge with tortoiseshell banding above six bobbin turned ebonised legs tied by stretchers and raised on bun feet. The stretchers inlaid with tortoiseshell panels and the apron with gilt beech drop finials. The stand reconstructed but incorporating original timbers and veneers.

Full description

It was always believed that this cabinet came to Oxburgh at the time of the 6th Baronet. In around 1830 Henry Bedingfeld and his new wife Margaret Anne moved into Oxburgh Hall. Henry’s parents had been living in Ghent and so the house had been unoccupied and sometimes let for the past 30 – 40 years and as a result, was badly in need of improvement and refurbishment. This was made possible by the money that Margaret brought as her inheritance which amounted to around £50,000. Although a list of purchases has not, as yet, come to light, it is known that Henry bought a great deal of furniture with which to fill the house and this cabinet is thought to have arrived at that time. He also employed the architect John Chessell Buckler to remodel the house and to create some new rooms such as the library. These changes were later recorded in a series of beautiful watercolours made by his daughter Matilda. However there is another possibility which is that the cabinet had been in the possession of the family from the time it was made. It is well known that the Bedingfelds had a close collection with Ghent, Brussels and Antwerp stretching back to the 17th century, giving them ample opportunity to acquire Flemish furniture. In a history of the family written in 1912 Katherine Bedingfeld reports that following a fire in the 1650’s caused by Cromwell’s Roundheads, some furniture was imported from Antwerp. She also records that Matthew, grandson of Sir Henry Bedingfeld (1511-83), lived in Brussels from 1646. The second Baronet who succeeded his father in 1684 left Lierre for Antwerp in February 1680 en route for England with the Duke of Gloucester at the time of the Restoration having emigrated at an earlier date. As we already know the 6th Baronet’s parents were living in Ghent at the beginning of the 19th century so perhaps this was a wedding gift from them. Finally – and perhaps most interestingly – one of the tortoiseshell cabinets in the private apartments appears to be the exact pair to one that is now at Charlecote, home of the Lucy family. Charlecote was remodelled in the middle of the 19th century the reason this may be important is that if the Lucy’s have records of where their cabinet came from, then it is possible that the Oxburgh cabinets came from the same source. It is hoped that a more thorough investigation of the family papers will help solve the mystery. We do know that by 1909 the cabinet was in the Saloon since it is recorded in a photograph taken for the March edition of the Magazine The Expert: The Illustrated Weekly for Collectors and Connoisseurs. It is common for series of images on furniture to derive from engraved sources or prints, and this appears to be the case in the present example. However there is no strong narrative theme carrying through the fourteen panels which is very unusual. The images comprise mid-distance landscapes tooled in very low relief in which ruined buildings, towers, farm buildings (thatched), trees, bushes and rocks are shown. In the foreground are boulders and antique/classical debris in the form of broken columns, capital, pedestals and sarcophagi. The figures are of children, putti, satyrs, hunters and farm labourers in typical Northern European dress. The animals are goats, rabbits, dogs, pigs/wild boar and cows. It is worth noting that antique ruins, putti, dancing children and satyrs were not generally included in Northern European prints of the period. Those artists who used them, were those who had spent time in Italy and had therefore been influenced by the Classical Renaissance. The conclusion that has been reached so far is that the artist whose work seems to correspond most closely with the Oxburgh panels is Herman van Swanevelt (1600-1655). This painter-etcher was also called Herman d'Italy or Il Erimita. Born in the Netherlands, he first went to Paris and then to Rome between 1629 and 1641. It was chiefly his etchings which made his landscapes accessible to a large public, and which decisively contributed to the development of the taste for landscape art into the eighteenth century. Swanevelt provided the link between the first group of Dutch Italianates who were led by Breenbergh and van Poelenburch and the second generation of Weenix and Nicholaes Berchem. His images include a selection of animals, satyrs, children, trees both standing and leaning, buildings including extensive ruins with Roman arches etc and antique/classical debris in on one title page for twelve views of Rome. There are also hunting scenes, with small figures, in the fore and middle ground. Throughout the sixteenth century and for the first half of the seventeenth century Antwerp was a great trading port as well as being a vibrant artistic and cultural centre. It had a truly international character and readily absorbed influences from many of other European countries. The artist Rubens came from Antwerp, as did Van Dyck and Teniers, naturally their style influenced many of the paintings that appeared on luxury goods and decorative objects produced at the same time. Prior to 1610 the centre for the production of luxury cabinets was Augsburg but after the Thirty Years War furniture making in Augsburg declined and the focus moved to Antwerp. Furniture manufacture in Antwerp was dominated by dealers who controlled the international market and were well-attuned to the current tastes. Cabinets such as this were sometimes known as collectors' cabinets, and some were supplied complete with contents such as precious jewels and small objects as well as naturalia. However given its lavish exterior it is probable that this type of cabinet was just made for show, and the drawers may have remained empty. Although work on comparable examples is only just beginning the two cabinets shown below appear to share some very similar features. Closer investigation of these may add to our understanding of the Oxburgh Cabinet. (James Weedon 2017) (Elizabeth Jamieson 2009)

Provenance

Bought in the 1830s in Antwerp, possibly by 6th Baronet Bedingfeld. By descent to sir Henry Bedingfeld 10th Bt (b.1943) and loaned by him until purchased by the National Trust in 1999.

References

Bedingfeld, 1912: Katherine Bedingfeld. The Bedingfelds of Oxburgh. Privately printed, 1912. Baarsen 2013: Reinier Baarsen, 'Seventeenth-Century European Cabinet-Making at Ham House' in Christopher Rowell (ed.), Ham House 400 Years of Collecting and Patronage, Yale, 2013, pp.194-203