Tent

Category

Textiles

Date

1725 - 1799

Materials

Bamboo, Leather, Cotton, Calico, Chintz, Iron

Measurements

5 m (Height); 25 m (Circumference)

Place of origin

India

Order this imageCollection

Powis Castle and Garden, Powys

NT 1180731

Summary

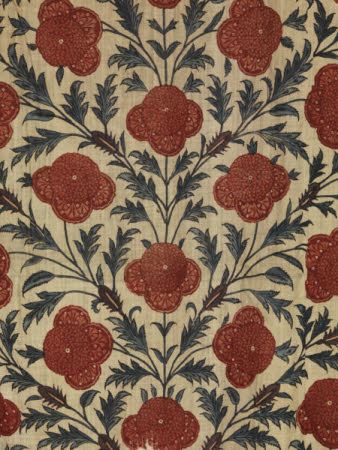

Polygonal tent, painted and stencilled chintz, Mughal India, makers unknown, c.1725-99. The tent has long been associated with the ruler of Mysuru, Tīpū Sultān (1750-99). Made up of four parts; roof and three qanāt (side panels). Each part is made up of three layers, with a decorated inner layer on a fine weave cotton, a middle layer with cotton webbing attached, and the outer layer in a plain coarser cotton. The valances, at the apex and the eaves, is red and white patchwork. Also bamboo battens with iron shoes, some integrated into a qanāt, and a leather onion at the roof apex. The internal decorative scheme is stencilled, printed and painted in a repeating vase, branch and flower design. Six panes of one qanāt (NT 1180731.2) are in a different style and feature birds and animals. All the qanāt and the roof use a colour scheme of red, turquoise, purple and green on a natural off-white background. The size of the tent when erected is estimated to be c. 5m high at the centre, with a circumference of c. 25m and an area of 58.5m.

Full description

This tent has been described as Tīpū’s military ‘campaign tent’. Tīpū Sultān issued an ordinance, Hukm-Nāmah, in 1792, which describes seven camp layouts. Each features Tīpū’s own tent, the bārgāh mu’alla (‘exalted tent of state’) or bārgāh-i khāss (‘privy tent of state’) at their centre. Visual evidence of South Asian tents, from miniature paintings, depicts polygonal tents such as this one as private, rather than as tents of state [Andrews, p. 31]. This tent is made up of qanāt (side panels) from different tents (see NT 1180731.1-3) and incorporates South Asian textiles from both the mid- and late-18th centuries. Cannibalisation of older tents to repair or form new tents was not unusual in this period, and many of the visible alterations to the tent are believed to date from before the tent was brought to Britain in 1801. Some parts of the tent may have been taken by Tīpū’s father when he overthrew the previous Wodeyar ruler in Mysuru in 1761. High quality painted and printed chintz fabrics were produced at places such as Burhanpur, Machilipatnam and Golconda, and the earlier textiles (c. 1725-50) may have originated from one of these sites [Stronge p. 24]. Similar designs can be seen at the Calico Museum of Textiles, Ahmedabad (No. 222) and the V&A, London (IS 131-1950). The later textiles (NT 1180731.2) may have been made in the south of the Indian subcontinent [Andrews p. 36]. Research Note on Provenance: Tīpū Sultān spent much of his reign engaged in the defence of Mysuru against encroachment by the British East India Company. In 1798, a renewed British campaign provoked the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War. On 4th May 1799, during the Siege of Srirangapatna, Tīpū was killed. In the immediate aftermath, the British army looted Srirangapatna. According to Colonel Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington, ‘Scarcely a house in the town was left unplundered, and I understand that in camp jewels of the greatest value, bars of gold etc etc have been offered for sale in the bazaars of the army by our soldiers, sepoys and followers. I came in to take command of the army on the morning of the 5th and with the greatest exertion, by hanging, flogging etc etc in the course of that day I restored order…’ [Dalrymple, p. 351] The resumption of control by the higher ranks of the army enabled the work of the prize committee to begin. Prize committees were responsible for ‘collecting, inventorying and disposing of booty seized from the enemy and for compiling detailed lists of who had served under whom in each campaign – thereby seeking to establish combatants’ entitlement to prize' [Finn p. 17]. They were intended to prevent exactly the kind of undisciplined plunder of captured cities and defeated people which Wellesley reported in the aftermath of Tīpū’s defeat at Srirangapatna. More than 1,000 commissioned officers took their allotted share in the captured property, which they kept, exchanged or sold to others. High-value, or high-profile items, were excluded from the prize committee’s remit, and given to senior British civil and military personnel, as well as the British royal family. [1] Not all articles were genuine: tenuous or spurious attributions to Tīpū Sultān have been identified in objects which were brought to Britain. Edward and Henrietta Clive shipped a tent, along with other items formerly belonging to Tīpū Sultān, to Britain in 1801 [Archer p. 29]. The tent was reputedly used at garden parties at Powis, when it was erected with tent pegs made in Britain of local timber. [1] ‘Tipu Sultan’s Amulet Case’, accessed online at https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/scottish-history-and-archaeology/tipu-sultan/tipu-sultan/tipu-sultans-amulet-case, 10/2/22.

Provenance

Reputedly used by Tīpū Sultān, ruler of Mysuru, until his death at the Siege of Srirangapatna in 1799. Taken from Srirangapatna after 1799. Acquired by Edward, 1st Earl Powis, and Henrietta Clive before 1801. Thence by descent to John George Herbert, 8th Earl Powis. Purchased by the National Trust in 1999.

References

Crill 2015: Rosemary Crill (ed.), The Fabric of India, London 2015 Stronge 2009: Susan Stronge, Tipu’s Tigers, London 2009 Andrews 2015: Peter Alford Andrews, 'Tipu Sultan's Campaign Tent', unpublished 2019 Dalrymple: W Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company, Bloomsbury 2019 2018 Finn: Margot Finn, ‘Material Turns in British History I: Loot’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 28, December 2018 Archer, Rowell and Skelton 1987 Mildred Archer, Christopher Rowell, and Robert Skelton, Treasures from India: The Clive Collection at Powis Castle, London, 1987