Monteith

probably John Austin

Category

Silver

Date

1689 - 1690

Materials

silver

Measurements

349 mm (Dia)

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Erddig, Wrexham

NT 1151486

Summary

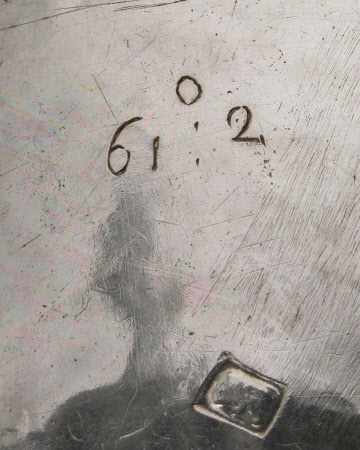

Monteith (bowl for punch and for rinsing and cooling glasses), sterling silver, probably John Austin, London, 1689/90. The circular bowl is raised from a single sheet of silver and has a notched rim with an applied, reeded lip moulding. It stands on a plain, waisted foot formed of seamed silver. The exterior of the bowl is separated by deeply chased lines into ten wide and ten narrow panels, alternating. The wide panels have contemporary flat-chased Chinese and Japanese inspired decoration in the style now known as chinoiserie, under a matted upper border. A different male figure is depicted in each, all but one astride parted rocks and variously accompanied by clouds, foliage, flowering plants, rockwork, the sun and a devotional figure. The narrow panels, which conform with the notches of the rim, are matted though two have been partially polished smooth at later dates to take shields of arms, one with a baroque foliate and scrolling cartouche of early 18th century fashion and the other with a rococo foliate cresting of the second half of the 18th century. The centre of the inside of the bowl is engraved with a crest within a baroque cartouche of circa 1700 consisting of foliage, scrolls, floral swags and scalework. Heraldry: One of the matted narrow panels is engraved with the arms of Hutton: gules a fess or between three cushions argent tasselled of the second [or] each charged with a fleur-de-lis of the field [gules]. These are for Matthew Hutton (d. 1728) whose daughter, Dorothy, married Simon Yorke I of Erddig. Another of the narrow panels is engraved with the arms of Yorke (argent on a saltire azure a bezant) quartering Hutton (as above) and Meller (argent three martlets sable beaked or, a chief dancettée of the second [sable]), impaling Cust (ermine on a chevron sable three fountains proper). These are for Philip Yorke I (1743-1804) and his first wife, Elizabeth Cust (1750-79). The inside of the bowl of the monteith is engraved with the crest of a boar’s head issuing out of a ducal coronet. This could relate to a number of families, none of which is connected to Erddig. Hallmarks: The underside of the monteith is fully marked with the sterling lion, leopard’s head crowned (for London), date letter ‘m’ for 1689/90 and maker’s mark ‘IA’ in script monogram in a shaped shield, probably for John Austin (David Mitchell, Silversmiths in Elizabethan and Stuart London, 2017, pp. 341-2). Scratchweight and inscription: On the underside of the monteith is the scratchweight ‘62 o[ounces]: 2[dwt]’. Adjacent is the engraved inscription ‘F*L’, probably the mark of a former owner.

Full description

A monteith is a punch bowl, the notched rim of which enables it also to be used to rinse and cool glasses. The stems of the glasses fit within the notches, their feet protruding and the bowls facing downwards into chilled water. The rim can either be integral, as in this example, or detachable as that of 1688/9 by Robert Cooper formerly at The Vyne and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum (accession no. M.25:1, 2-2002). Monteiths emerged in the 1680s and the first account of the form is given by the Oxford antiquarian Anthony Wood who recorded in his diary in December 1683: ‘This yeare in the summer time came up a vessel or bason notched at the brims to let drinking glasses hang there by the foot so that the body or drinking place might hang in the water to coole them. Such a bason was called a ' Monteigh,' from a fantastical Scot called ‘Monsieur Monteigh’, who at that time or a little before wore the bottome of his cloake or coate so notched UUUU.’ (Andrew Clark (ed.), The Life and Times of Anthony Wood, volume 3, 1894, p. 84). The identity of this ‘fantastical Scot’ has not been established although one candidate is William Graham, 8th Earl of Menteith and 2nd Earl of Airly (c1634-94). He was, however, deeply indebted and had consequently lost the right to the earldom of Menteith in 1670 so is not a very likely leader of fashion. The earliest surviving examples in silver of monteiths date from just a year after Anthony Wood noted their advent, including that marked for 1684/5 by George Garthorne in the Ashmolean Museum (see Timothy Schroder, British and Continental Gold and Silver in the Ashmolean Museum, 2009, vol. 2, cat. 226, pp. 606-610). This shares the chinoiserie decoration found on the Erddig monteith as do others of the 1680s such as one of 1685/6, also by Garthorne, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (acc. no. 1975.711), another of the same year with the maker’s mark ‘D.B’ at the Art Institute, Chicago (ref. 1947.483) and that of 1688/9 by Robert Cooper at the V & A (see above). Two more bear, as does Erddig’s, the maker’s mark ‘IA’ in monogram, now attributed by David Mitchell to John Austin and previously mistaken in some instances for ‘TA’. These are of 1685/6 (Duke’s Auctions, Dorchester, 8 December 2023, lot 2) and 1688/9 (Colonial Williamsburg, ref. 1960/581). For a decade or so from around 1680 there was little short of a frenzy for chinoiserie on silver, undertaken predominantly by unidentified London-based specialist chasers, and this was part of a wider vogue for items from or inspired by east and south Asia. Chinese and Japanese porcelain and lacquer and Indian textiles were imported in great quantities, and they were available as inspiration for London-based designers alongside designs for Restoration stage scenery and such illustrated books as Johan Nieuhof’s An Embassy ... to ... China of 1665 (translated into English 1669), Athanasius Kircher’s China Illustrata (1667) and Olfert Dapper’s Atlas Chinensis (1671). These sources would have been interpreted, merged and embellished by pattern drawers with the intention of satisfying the desire for something playful, exotic and highly fashionable. It is rare consequently for details to be able to be matched to an exact source but one of the male figures on the Erddig monteith, with an enormously wide brimmed hat, has been suggested to derive from an engraving of a mendicant in Nieuhof’s Embassy (David Beevers (ed.), Chinese Whispers: Chinoiserie in Britain 1650-1930, 2008, cat. A11, pp. 86-7). The source for the devotional figure in another of the scenes, though not yet identified, must have been the same as that employed, with a different accompanying male figure, on a monteith of 1688/9 by George Garthorne in the Milwaukee Art Museum (ref. M2003.90). The chasing style and composition of scenes on John Austin’s 1688/9 monteith at Colonial Williamsburg (as above) are the closest of all those examples thus far quoted to what is found on Erddig’s monteith, and both may well be attributable to one hand or at least have drawn on the same pattern-maker’s designs, perhaps in a shared workshop. As to the identity of the chaser, thus far only one name has been suggested - Andrew Raven who is known to have been employed by the goldsmith-banker, Sir Richard Hoare (information from Dr David Mitchell). There is no evidence to confirm that he chased the Erddig monteith, however, and the general anonymity of such workers and lack of study of individual hands make it impossible currently to hazard an attribution. From a succession of ownership marks and engraved arms it is clear that the Erddig monteith changed hands a number of times in its early history. The initials ‘F*L’ engraved on the underside may well relate to the original purchaser, who remains unidentified, but the engraved cartouche within the bowl looks to date from a decade or so after the monteith was made and was perhaps undertaken for a second owner. He or she also cannot be identified as the armorials contained therein were erased, probably after another change of ownership, and replaced by the crest of a boar’s head issuing from a ducal coronet. According to Fairbairn’s Crests … of Great Britain and Ireland (1968, plate 102, no. 14), that crest was held by some thirty different families, none with an obvious connection to Erddig or to Matthew Hutton (c.1676-1728) of Newnham, Hertfordshire, who is the first identifiable owner. His arms are engraved on one of the exterior narrow matted panels and their style accords with a purchase in around 1710-20. Hutton, an immensely wealthy merchant and landowner who was Queen Anne’s Sergeant-at-Arms from 1701 to 1710, and later an attorney with the Exchequer’s office, would have bought the monteith second hand and thus saved money by only paying the metal value, rather than also for fashioning as would have been the case with a new piece. He was in a good position to keep an eye out for such a bargain, his wife Barbara being the sister and niece respectively of George Wanley and James Chambers, early partners in the goldsmith-banking business that became Goslings Bank. By his will (The National Archives, PROB 11/626/256), Barbara Hutton (c.1692-1750), in addition to her jointure, received outright her jewels together with his coach, chariot and coach horses and also the use, without the power to dispose, of his house and estate at Newnham in Hertfordshire together with ‘all my Plate Houshold Goods ffurniture and Utensills’. During her long widowhood she commissioned additional silver, notably a fine pierced bread basket of by Peter Archambo (NT 1151469), and on her death the entirety passed in succession to her two sons, Matthew II (d. 1764) and James (d. 1770). As James had no legitimate progeny he bequeathed by his will (The National Archives, PROB 11/959/212) the bulk of his estate to his nephew, Philip Yorke I (1743-1804), but with a life interest to his sister and Philip’s mother, Dorothy Yorke (1717-87), in his London house on Park Street, Mayfair together with the contents thereof including plate. This is listed in an inventory of 1770 surviving amongst the family papers in Flintshire Record Office (ref. D/E/2419) and includes much of the Hutton silver surviving at Erddig today, including the monteith. Given that the monteith is engraved in addition to the Hutton arms with those of Philip I impaling Cust for his first wife, Elizabeth (1750-79), it must have been handed over to him during Dorothy’s lifetime as she outlived her daughter-in-law. Thereafter the monteith passed with the Erddig estate. James Rothwell, National Curator, Decorative Arts (with information from Emile de Brujn, Assistant National Curator, Decorative Arts). June 2024

Provenance

Acquired second-hand by Matthew Hutton I (d. 1728); his widow Barbara Hutton (née Wanley, c. 1692-1750); their sons Matthew Hutton II (d. 1764) and James Hutton (d. 1770); their sister Dorothy Yorke (née Hutton, 1717–87); her son Philip Yorke I (1743-1804); thence by descent until being donated to the National Trust in 1973 along with the Erddig estate and the rest of the collection by Philip Yorke III (1905–78).

Credit line

Erddig, the Yorke Collection (National Trust)

Marks and inscriptions

Base: A * L [and hallmark]

Makers and roles

probably John Austin, manufacturer