Portrait of Sophia Fermor, Countess of Granville

Category

Art / Sculpture

Date

c. 1744 - 1745

Materials

Ivory, Wood

Measurements

70 mm (H)70 mm (W)

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Ham House, Surrey

NT 1140227

Summary

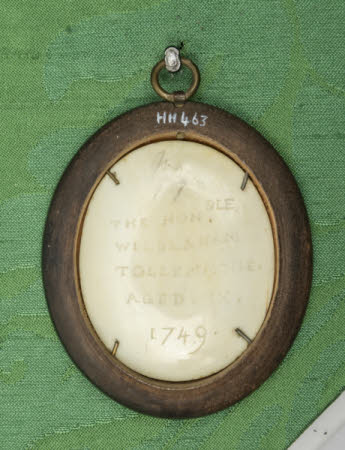

Ivory; portrait of Sophia Fermor, Countess of Granville (1721-1745); British; c. 1744-45. In the form of a circular ivory medallion, the sitter depicted in profile at bust length, facing to her left. One of five ivory portrait and subject reliefs within a single frame, in the Green Closet of Ham House.

Full description

A portrait of Sophia Fermor, Countess of Granville (1721-1745) in the form of a circular ivory medallion, the sitter depicted in profile at bust length, facing to her left. She is dressed in a robe in the classical style, fastened with a brooch at the left shoulder; her hair is cut short and contained within a net fastened to the head with a band, just a lock escaping at the side and passing over the ear. One of five small carved ivories in the Green Closet of Ham House, four of which are portraits of members of the family living during the first half of the eighteenth century (for the others, NT 1140217; 1140225; 1140226; 1140236). Sophia Fermor was the daughter of Thomas Fermor, 1st Earl of Pomfret. In 1744 she married as his second wife John Carteret, 2nd Earl of Granville, making her the step-mother of the subjects of two of the other ivory portraits at Ham House, Lady Grace Carteret, Countess of Dysart (NT 1140217) and her sister Frances Hay, Marchioness of Tweeddale (NT 1140226). Sophia Fermor died in October 1745, just a year after her marriage and a couple of months after the birth of her daughter, also Sophia. A pastel portrait of Sophia Fermor before her marriage done by the Venetian artist Rosalba Carriera was subsequently published as a mezzotint print by John Faber which went through many editions, the later ones with the popularising title ‘The Inn-keepers handsom Daughter’. The four portraits of members of the Carteret and Tollemache family are somewhat diverse in their conception; Wilbrahim Tollemache is conventionally represented in contemporary dress, whilst his mother Lady Grace Carteret, Countess of Dysart, is depicted in a classicising profile portrait that, with her elaborate coiffure with flying loose locks, somewhat recalls all’antica portrait reliefs of the sort that were popular in sixteenth-century Venice. The two most unusual images are however those of Lady Frances Carteret, later Marchioness of Tweeddale, and Sophia Fermor, Countess of Granville who, despite being their junior in age, was briefly the stepmother of Lady Frances and Lady Grace. These two women are presented in extremely austere neo-classicising depictions of a sort that is seen in some male eighteenth-century portraits. Good examples are Edmé Bouchardon’s 1729 portrait bust of Lord John Hervey, 2nd Baron Hervey of Ickworth (Ickworth; NT 852228), Louis-François Roubiliac’s bust of Philip Dormer Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, made in 1745 as a pair for an antique bust of Cicero (National Portrait Gallery, London), or the marble bust of Dr Antonio Cocchi, made by Joseph Wilton in 1755 (Victoria & Albert Museum, London). In all these portraits the sitters are represented without wigs and as highly naturalistic if severe portraits. In ivory carving, Thomas Hollis (1720-74) commissioned from the Roman ivory carver Andrea Pozzi, to commemorate the sitter's birthday on 14 April 1752, a pair of portraits of himself and his companion Thomas Brand Hollis. Whilst the latter is depicted in profile wearing contemporary clothing, Hollis was depicted bare-chested and without his wig (Joan Coutu, Then and Now. Collecting and Classicism in Eighteenth-Century England, Montreal/London 2015, pp. 168-69, figs. 5.3and 5.4). There are also some parallels with the double portrait in the Victoria & Albert Museum of William Pitt and Elizabeth Windham, dated 1736 (Marjorie Trusted, Victoria and Albert Museum. Baroque and Later Ivories, London 2013, no. 149), although the portraits are less severe in the V&A relief. Although therefore a number of examples of severely neo-classical portraits of men from the middle decades of the eighteenth century are known, portraits of women in this mode are extremely rare. Unlike Thomas Hollis, John Carteret, Lord Granville, the father and husband of Lady Frances and Lady Sophia, was not a noted radical, which might otherwise have explained the treatment of the two women. It must be assumed that the group of ivory reliefs were intended as intensely private images within the contexts of the families of the sitters. Although the portraits may not all have been made at the same time, they can be dated to the second half of the 1740s. The portrait of Sophia Fermor is likely to date from 1744-45, since she only married Earl Granville in April 1744 and died just eighteen months later in October 1745, as a result of complications in childbirth. The very similar portrait of Lady Frances Carteret is likely to date from the same time. Some of the most original ivory portraits of British sitters at this time were made in Rome, but in the absence of any evidence that the four subjects travelled to Italy, it seems more likely that these ivories were carved in London, perhaps by an immigrant sculptor from Flanders or France. One possible candidate might be the Antwerp-born Gaspar van der Hagen (active 1744-1769), who worked for a time in Michael Rysbrack's workshop and made sculptures in both marble and ivory, specialising in small ivory heads. Jeremy Warren January 2022

Provenance

Presumably the 4th Earl and Countess of Dysart; thence by descent, until acquired in 1948 by HM Government when Sir Lyonel, 4th Bt (1854 – 1952) and Sir Cecil Tollemache, 5th Bt (1886 – 1969) presented Ham House to the National Trust. Entrusted to the care of the Victoria & Albert Museum until 1990, when returned to the care of the National Trust, to which ownership was transferred in 2002.