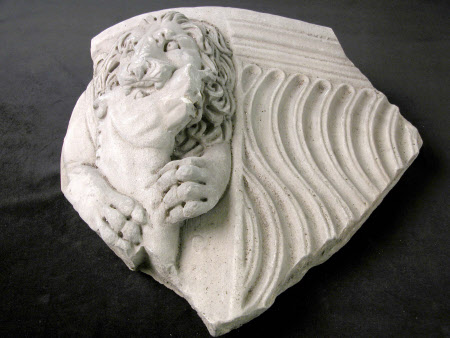

Fragment of strigillated sarcophagus showing a lion eating a horse

Category

Art / Sculpture

Date

200 AD - 299 AD

Materials

Marble

Measurements

400 mm (H); 470 mm (W); 190 mm (D)

Order this imageCollection

Biddulph Grange Garden, Staffordshire

NT 104584

Summary

Fragment of strigillated sarcophagus showing a lion eating a horse, Rome, 3rd century AD. A fine classical sculpture of white marble. Part of the corner of a large sarcophagus. The sides of the sarcophagus deeply carved with a wavy motif, fine aratral cyma moulded rim.

Full description

Fragment of strigillated sarcophagus showing a lion eating a horse, Rome, 3rd century AD. A fine classical sculpture of white marble. Part of the corner of a large sarcophagus. The sides of the sarcophagus deeply carved with a wavy motif, fine aratral cyma moulded rim. The fragment is broken on its sides and bottom. A portion of the curving top edge and the original back are preserved. The front portion of the horse’s head is broken as is the last finger of the front right paw of the lion. The carving is good and uses finished drill work as well the flat chisel (visible in details such as the lion’s lead or the hairs of the horse’s mane). The back is roughly picked. This well-carved fragment shows a rounded corner (viewer’s left) of a strigillated sarcophagus. The corner is decorated with a lion, wearing an ornate lead, that is devouring a horse. At Biddulph Grange it was located on the viewer’s left below the male head. In the wall its value lay in its representation of God's animals. The Biddulph Grange fragment shows a lion who looks outward, turning to his right, and bites the brow, just above the eye, of a horse. The horse is viewed in right profile; its right ear flattens in its horrible moment. The front right leg of the lion wraps around the neck of the horse and the paw rests on its front quarters. The left paw of the lion digs in and scratches the neck of the horse. The claws of the lion’s paws are rendered as articulated fingers. The scratch, which the front left claw makes, is carefully rendered, as are details of the manes and facial details of both animals. Interestingly the lion wears a lead, with engraved borders. The strigils of the sarcophagus are broad and flat. The upper border has a complex moulding. Strilligated sarcophagi were extremely popular in the third century and take their name from the strigil-like device, an almost S-curve, that comprise their principal form of decoration. The strigil motif suggests movement and decorated effectively large spaces; it moreover served to focus attention on the few figural elements of such sarcophagi. The direction and quantity of the strigils and the location of figural decoration have been recorded in fourteen variations (i.e. there were standard layouts). The usual location for narrative scenes or inscriptions were at the front corners and at the centre. One of the most popular types in the third century featured lions, often devouring their prey at the corners as in the Biddulph Grange example. These lions were menacing reminders of death and the fragility of life. The Biddulph Grange example wears a lead; in many examples the lions are held by figures which represent seasons and so again emphasize the cycle of life. One of six sculptural fragments (104579-104584) carefully set into the wall on the left of the entrance to the Geological Gallery of Biddulph Grange which opened in 1862. The foyer area, the left wall of which they decorated, preceded the gallery. In the gallery, the seven days of Creation were demonstrated one by one, on the wall to the visitor’s left, by means of geological evidence, rocks and fossils. In both the entrance and in the gallery, the objects were set into the wall with deliberate illustrative purpose. In both the entrance and the gallery, the objects are stone and somehow marked, and through their ancient markings demonstrate the truth of the creation story. In the entrance wall, five of the objects were carved in the Greco-Roman period; the other object was carved later but the creators of the gallery may not have known that. The objects set into the gallery wall illustrate a geological approach that was intended to confirm scientifically the Christian understanding of creation. The objects set into the entrance were a stone and sculptural re-enactment of the traditional approach to the Christian creation scene which the gallery would confirm scientifically. In the Biddulph Grange wall, a bearded paternal figure (104580) peers out and over a scene below; the actual object, a head of Goliath with Renaissance origins, stands for God the Father. Below him, to the left and right, are male and female heads (104581 & 104582). The male head is bearded with a lined and tried face, in fact the head probably of Herakles from the Roman period. Herakles, the mortal son of Zeus, who had to struggle through 12 labours to redeem himself and get entry to heaven, is a brilliant choice for Adam. One is left to wonder whether this choice was coincidence or whether the creators of the gallery were extremely well-versed. The pendant to this male head, Adam, is female head is modestly veiled with symmetrical ageless features; she is intended at Biddulph Grange to be Eve. In reality, she is the head of the ideal woman from a classical Greek tombstone. Again the choice of an image that was made as a representation of the most appropriate qualities of a demure and modest wife for an image of Eve is exceptionally well-conceived. Both of these choices would seem to confirm the longevity of the Christian story; that is, even in societies where the story was not espoused, the fundamental concepts behind it existed. Below these two human heads, on the left and right, are fragments from Roman sarcophagi which show animals and their natural plight in life. On the left (104583), a wild boar is hunted by men and on the right (104584), a noble horse is taken down by a ravenous lion. These are the marvellous creatures which God created and which are in a natural state of conflict with other beings. These images were displayed on Roman sarcophagi precisely because they represented the simplicity of nature, both its natural beauty and cruelty. At the bottom of the scene, in antithesis to God the Father, is a dark piece of porphyry, carved to represent the mouth and beard of a man (104579). Its interpretation is less clear. It may stand for the solid basis that God created for his creatures. It is a magnificent stone which in its fragmentary state is virtually devoid of animation. The space of the wall furthermore may have been punctuated by a lamp at the centre of these sculptural fragments. A decorative stone bracket projects from the centre and must have carried some object. A lamp or torch placed on the bracket would have given illuminated the dark passage and represented the light of God. All of the sculptures are carefully chosen fragments; they each have a specific aesthetic and compositional value. They would seem to have been purchased for this purpose and may even have been broken (with the exception of 104579 into their current shape for this purpose. The composer has selected with attention and each of the fragments (with perhaps the exception of 104580 is attractive and well-carved. Symbolically the reuse of objects from “ancient” cultures suggests the antiquity and venerable veracity of the Creation scene. (Exert from J. Lenaghan 2017 "Biddulph Grange. Report in Wall left of entrance to gallery")

Provenance

Originally from Geological Gallery Vestibule.