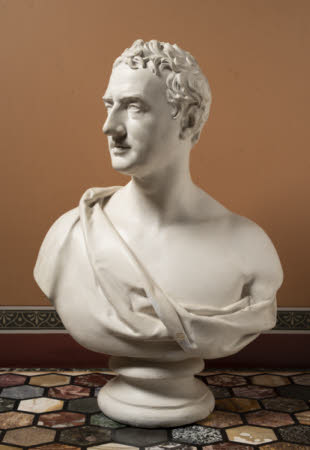

Robert Stewart, 2nd Viscount Castlereagh and 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, KG, GCH, MP (1769–1822)

after Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey RA (Norton, nr. Sheffield 1781 – London 1841)

Category

Art / Sculpture

Date

c. 1821 - 1830

Materials

Plaster

Measurements

765 x 530 x 255 mm

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Ickworth, Suffolk

NT 852242

Summary

Sculpture, plaster; portrait bust of Robert Stewart, 2nd Viscount Castlereagh & 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, KG, GCH, MP (1769–1822); workshop of Sir Francis Chantrey (1781-1841); c. 1822-30. A portrait by Sir Francis Chantrey of the Irish-born politician and statesman Lord Castlereagh, who as Foreign Secretary became a key participant in the negotiations at the Congress of Vienna following the final defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte. At an earlier stage in his career, Castlereagh was also instrumental in enabling the passing of the Act of Union by the Irish Parliament. The bust is one of many copies of a signed and dated portrait bust made by Chantrey in 1821, formerly in the Londonderry collection. It bears on the back the same signature and date, suggesting it was cast from that prime version, presumably under the sculptor's supervision. The 5th Earl of Bristol would certainly have known Castlereagh well from his time as a member of Parliament in the 1890s and early 1800s.

Full description

A portrait bust in plaster of Robert Stewart, 2nd Viscount Castlereagh & 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, cast from a marble original by Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey RA (Sheffield 1781 – London 1841). The subject is depicted at bust length, a toga-like drapery wrapped around him and with the left shoulder left bare, facing to his right, his hair short. Mounted on a turned socle. Viscount Castlereagh was one of the key figures in British and European politics for a period of more than two decades, until his death by suicide in 1822. He was born Robert Stewart, the only surviving son from the first marriage of the 1st Marquess of Londonderry. In 1790 the young man entered Parliament as MP for County Down, enjoying a meteoric rise through British politics to eventually become Prime Minister in all but name. In 1798, as Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Stewart was wrongly blamed for the violence employed to suppress the rebellion that year in Ireland. However, he supported the union of Ireland with Britain and was subsequently instrumental in ensuring the passing of the 1801 Act of Union. From 1802 until his death Castlereagh was a member of the British cabinet continuously, excepting only the period 1809-12, when he resigned after a dispute with George Canning, which ended in a duel and the collapse of the administration. In 1812 he returned to government as Foreign Secretary, in which post he helped to bring the Napoleonic wars to a conclusion, before playing a key part in the Congress of Vienna, which aimed to reach a settlement with France and to create a balance of power to ensure peace in Europe. Castlereagh’s far-sighted diplomacy and work to create consensus led to an unprecedented period of peace in Europe. With a reputation as a staunch reactionary, Lord Castlereagh tended to excite violent reactions among his contemporaries, enthusiasm from some and condemnation on the part of others. In 1821, just over a year before his own demise, he succeeded as 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, on the death of his father. His suicide in 1822 is thought to have been driven by overwork, anxiety and hostility engendered by his efforts on behalf of Catholic Emancipation. Francis Chantrey is one of the greatest of English sculptors, certainly the finest portrait sculptor working in Britain in the nineteenth century. Born in modest circumstances near Sheffield, he was largely self-taught and, unlike many other young artists, did not have the chance as a young man to study in Italy, although he would travel there in 1819. He began his career as a woodcarver in Sheffield, but was living in London by 1809, when he married. Chantrey’s first major success came with a portrait bust of the Rev. J. Horne Tooke, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1811 (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). He would in the course of his career make numerous church and public monuments in marble and in bronze, but it was as a maker of portrait busts that he was especially admired by his contemporaries. Chantrey had a particular ability to express the softness of flesh through the hard material of marble, whilst retaining a sense of the bone structures beneath. His contemporary J.T. Smith praised his busts for ‘their astonishing strength of natural character, for the fleshy manner in which he has treated them, which every real artist knows to be the most difficult part of the Sculptor’s task.’ (J.T. Smith, Nollekens and his times, 2 vols., London 1920, I, p. 227). Likewise his friend George Jones wrote that ‘His busts were dignified by his knowledge and admiration of the antique, and the fleshy, pulpy appearance he gave to marble seems almost miraculous when operating on such a material; the heads of his busts were raised with dignity, the throats large and well turned, the shoulders ample, or made to appear so; likeness was preserved and natural defect obviated.’ (Jones 1849, p. 172). The portrait bust of Lord Castlereagh was the first of a series of images made by Chantrey of Tory politicians, which would be regularly shown at the Royal Academy. The prime version of the portrait was commissioned in 1820 by Castlereagh himself (Yarrington, Lieberman, Potts and Barker 1991-1992, pp. 145-46, no. 125b) and was then exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1821 (no. 1132). Signed and dated 1821, it became one of a group of six portrait busts, mainly depicting members of the Londonderry family, that was long displayed in the Inner Hall at Londonderry House, mounted on yellow scagliola pedestals. Together with another version of the bust of Castlereagh, it was among the sculptures from Londonderry House sold at auction in 1962, following the sale and demolition of the family’s London residence, and is now in the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven (Inv. B1977.14.3). Chantrey’s original plaster model for this major portrait is in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (Inv. WA1842.81; Penny 1992, no. 689; Eustace 1997, pp. 88-90, no. 6) and drawings for it are in the National Portrait Gallery. Numerous other replicas of the portrait survive, most of them made by Chantrey’s studio. They include versions in marble in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG 687, dated 1822), the Royal Collection (RCIN 35411, commissioned 1828); the Wellington Museum, Apsley House, London and the Travellers’ Club, London. In National Trust collections, there are marble examples at Mount Stewart (NT 1542341) and at Powis Castle (NT 1185532). The plaster version at Ickworth is of particular interest since, signed and dated 1821 on the back, it appears to have been cast from the prime version made for the Londonderrys, perhaps around the time that it was being publicly exhibited in London and presumably in Chantrey's workshop and under the sculptor's supervision. Like many of Chantrey’s busts of male sitters, his portrait of Lord Castlereagh depicts the sitter dressed not in contemporary apparel, but instead in a toga-like drape evoking the antique. Here, however, the unusual device of leaving the left shoulder bared seems to have been a deliberate choice on the part of the famously handsome Castlereagh. The sculptor’s friend and early biographer George Jones wrote of how King George IV, the Duke of Sussex and Castlereagh were all ‘so struck with Chantrey’s power of appreciating every advantage of form, that they bared their chests and shoulders, that the sculptor might have every opportunity that well-formed nature could present.’ (Jones 1849, p. 172). The naked shoulder lends the portrait a somewhat sensuous air, whilst the portrait’s studied informality is augmented by the sculptor’s turning of the head to the sitter’s right, creating the sense that he is engaged in conversation. The Duke of Wellington’s friend Mrs Arbuthnot saw the unfinished bust in Chantrey’s studio in March 1821, writing in her diary that ‘It was not quite finished, but it will be wonderfully like and has just the beautiful expression of his countenance when he speaks.’ (Arbuthnot 1950, I, p. 85, 26 March 1821). Chantrey’s early biographer John Holland suggested that it was after his return from Italy that Chantrey produced four of his very finest busts: Castlereagh, the painter Thomas Phillips, William Wordsworth and Sir Walter Scott. More recently Margrate Whinney commented on how in the portrait of Castlereagh ‘the neck rises superbly out of the shoulders of the noble, large bust’ and how, unlike in so many other portrait busts in which it is the eyes that most easily catch the viewer’s attention, ‘In this bust the mouth seems the most vital feature of the face.’ Jeremy Warren July 2025

Provenance

Bristol collection, by descent at Ickworth to Frederick William Hervey, 7th Marquess of Bristol (1954-99); Sotheby’s, The East Wing, Ickworth, Suffolk, 11-12 June 1996, lot 99 (wrongly catalogued as the 2nd Earl of Liverpool) ; acquired by the National Trust for £4,600, with the help of funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Marks and inscriptions

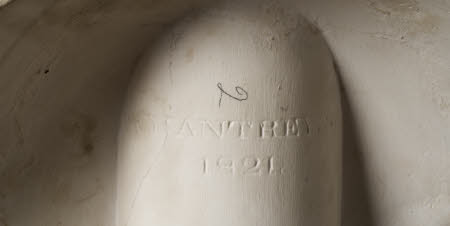

On back:: CHANTREY SC. / 1821

Makers and roles

after Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey RA (Norton, nr. Sheffield 1781 – London 1841), sculptor

References

Jones 1849: George Jones, Sir Francis Chantrey, RA: Recollections of his Life, Practice and Opinions, London 1849, p. 172. Holland 1851: John Holland, Memorials of Sir Francis Chantrey, Sheffield 1851, p. 277. Smith, John Thomas,. Nollekens and his times 1920. Arbuthnot, Harriet, 1793-1834 journal of Mrs. Arbuthnot 1820-1832 / 1950. Whinney 1992: Margaret D. Whinney, Sculpture in Britain, 1530-1830, Yale University Press, 1992, pp. 418-22, Pl. 312. Yarrington, Lieberman, Potts and Barker 1991-1992: Alison Yarrington, Ilene D. Lieberman, Alex Potts and Malcolm Barker, ‘An Edition of the Ledger of Sir Francis Chantrey R.A., at the Royal Academy, 1809-1841, The Volume of the Walpole Society, 1991-1992, pp. 145-6, no. 125b. Penny 1992: Nicholas Penny, Catalogue of European Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum, 1540 to the Present Day, 3 vols., Oxford 1992, III, no. 689. Dunkerley 1995: Samuel Dunkerley, Francis Chantrey Sculptor. From Norton to Knighthood, Sheffield 1995, pp. 61, 63, Pl. 18. Eustace 1997: Katharine Eustace, ed., Canova. Ideal Heads, exh. cat., Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 1997 Roscoe 2009: I. Roscoe, E. Hardy and M. G. Sullivan, A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain 1660-1851, New Haven and Yale 2009, p. 249, no. 422.