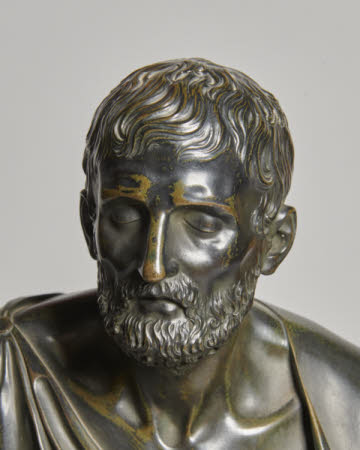

Belisarius and his Guide

Antoine-Denis Chaudet (Paris 1763 - Paris 1810)

Category

Art / Sculpture

Date

c. 1791 - 1810

Materials

Brass, Bronze

Measurements

496 mm (Height); 356 mm (Diameter)

Place of origin

Paris

Order this imageCollection

The Argory, County Armagh

NT 565234

Summary

Sculpture, bronze; Belisarius and his Guide; after Antoine-Denis Chaudet (1763-1810); c. 1791-1810. A bronze sculpture depicting the Byzantine general Belisarius, blinded on the orders of the Emperor Justinian. Chaudet’s original sculpture was exhibited at the Salon in 1791, when anti-royalist sentiment was reaching new heights.

Full description

A bronze sculpture depicting the Byzantine general Flavius Belisarius (505-565 A.D.), after he had been blinded and expelled from court on the orders of the Emperor Justinian. Belisarius is depicted seated on a plain rectangular block, dressed in a loose robe fastened at the right shoulder with a brooch, a cloak over his left shoulder. He wears his old military belt about his waist, and his helmet, in which he would now as a beggar collect alms, is at his feet. It is decorated with a winged griffin and a frieze of studs. He holds a staff in his left hand and his sightless eyes gaze emptily outwards. With his right hand he holds onto the shoulder of his guide, a young boy seated at Belisarius’s feet, lying against him and gently sleeping. Balisarius’s left foot projects out beyond the edge of the circular base, which has a textured surface, and on the front of the upper part of which is the inscription ‘DATE OBOLUM BELISARIO’ [Give alms to Belisarius]. Below the upper base is a stepped plain circular base. It has not been possible to examine the underside of the Argory bronze, which would provide evidence as to how the bronze was made. But the underside of the cast recently sold at Bonham’s shows that the composition was cast in several sections - the figure groups, the rectangular seat and the base. These elements were bolted together following casting. The lower part of Belisarius’s staff was also cast separately. Flavius Belisarius is often regarded as the last great Roman general. He served the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (483-565) over many decades, leading efforts against the Vandal kingdom in Africa and the Goths in Italy and restoring huge swathes of territory to Eastern Roman rule. However, in 563 A.D. and towards the end of his life, Belisarius was accused of conspiracy against the emperor and was confined for a year in his palace, before his innocence was recognised and his honours restored to him. The more dramatic stories of Justinian’s jealousy of Belisarius’s success are a later invention. These narratives saw Justinian becoming increasingly uncomfortable with his general’s successes and his popularity, at first starving him of resources for his armies and eventually removing him from command, having his eyes put out and expelling him from the court. The blind Belisarius was then forced to wander the streets of Rome, led by a young boy and begging for alms, as evoked in the inscription on the bronze at the Argory. One of his former soldiers then found him and gathered together a group of other veterans, who confronted the Emperor and forced him to issue a pardon. In the eighteenth century, the story of Belisarius's fall from favour at the hands of the Emperor Justinian became popular, as a cautionary tale against tyranny and the fickle favour of kings. In 1767 the French author Jean-François Marmontel published his influential and incendiary novel Bélisaire. Telling the more dramatic story of the general’s treatment by his emperor, Marmontel's text was quickly seen as a denunciation of absolute power and the luxurious and licentious behaviour of courts, Justinian as a veiled representation of king Louis XV and Byzantium as the court at Versailles. The book was quickly censured as seditious in France and publicly burnt, but it went into many editions in French, English and other languages. An edition published in Philadelphia, on the eve of the American Revolution, included on its title page a preamble summing up the views of those who saw Belisarius as a symbol of opposition to the established orders: ‘A man who possessed the most immoveable fidelity, and practised the most disinterested patriotism, in the court of a weak emperor, surrounded by a junto of as corrupt and abandoned ministers, as ever enslaved and disgraced humanity; whose malice and envy remained unsatiated, till by misrepresentation and perjury they accomplished the downfall of this greatest and most excellent of all human beings, in whose amiable and exalted character every virtue exists that is admirable or desirable’ ('Belisarius, the heroick and humane Roman general', published by J. Crukshank, Philadelphia 1770). In France, Marmontel's novel and the ideas it was seen as conveying made it an object of sometimes violent debate between progressive and more conservative movements, and the figure of Belisarius accordingly became one of the great subjects in painting and sculpture in the closing decades of the eighteenth century. Among paintings were those of 1779 by Jean-François Peyron (version in National Gallery, London) and Jacques-Louis David’s ground-breaking neoclassical painting 'Belisarius receiving Alms' of 1781 (Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille). Sculptures of the subject were made by a number of sculptors, among them Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828), but these were all head studies of Belisarius. Thus the sculpture exhibited by Antoine-Denis Chaudet was in fact the first major sculptural work to treat the subject as a history sculpture. Chaudet was one of the most gifted sculptors working in France in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but never quite achieved his promise, in part because he was dogged by poor health, but also because in his later years he became virtually the official portraitist in sculpture of the Emperor Napoleon, so his activity came to be dominated by the production of portraits of the emperor. His famous portrait of Napoleon in herm form was reproduced in numerous versions by the sculptor as well in other workshops. There are several examples in the National Trust collections, at Anglesey Abbey (NT 516583), Felbrigg (NT 1401964) and Wallington (NT 585732). Chaudet, who had returned to Paris in 1787, after three years studying in Rome, became an enthusiastic supporter of the Revolution, participating in events such as the storming of the Bastille. It is perhaps therefore to be expected that he would have wished to take part in the 1791 Salon exhibition, the first to be organized by the National Convention following the Revolution and given the title ‘Salon de la Liberté’. Chaudet exhibited there a terracotta group of Belisarius, which is lost, but a larger plaster version in the Musée du Louvre (Inv. LL 82; on long-term loan to the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille; Hubert 1959) must have been made from it, in preparation for a marble version which seems never to have been executed. The artist depicts the scene from the beginning of the novel, when Belisarius and his companion enter a tavern where a group of men, among them Tiberius, the son of Justinian, are loudly denouncing the evils of their present times. After Belisarius has been recognized by Tiberius, he is offered a bed, but replies that for himself he simply needed some straw, ‘I have slept far worse from time to time, he said, just have some care for this child who is my guide, and who is more delicate than me.’ However, the Louvre plaster and most of the bronze versions bear the more general invocation in Latin, ‘DATE OBOLUM BELISARIO’, ‘Give alms to Belisarius’. This is taken from the inscription on a stone block on the right-hand side of Jacques-Louis David’s painting of the subject in Lille. Chaudet and David had met in Rome in 1784 and became good friends, David presenting the sculptor with a drawing based on a Roman relief in Naples, which David used as his source for the figure of Crito in his celebrated Death of Socrates in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, painted in 1787. The drawing, also now in the Met, was in turn used by Chaudet for his figure of the seated Belisarius (Draper 2007). A bronze cast of this sober but intensely moving composition was exhibited at the Salon in 1796, where it was described as ‘worthy of the taste and spirit that this skilled sculptor is accustomed to put into his works (‘digne du gout et de l’esprit que ce sculpteur habile met dans ses productions’. Draper 2007, pp. 228, 231, note 15). The bronze model evidently enjoyed a short period of popularity, with casts of the Belisarius featuring in several sales held in Paris in the first half of the nineteenth century. The first such recorded auction was at the Mont de Piété in 1803 (18-25 April 1803, lot 331), in which the example sold was described as ‘admirably cast and very well-chased’ (‘d’une fonte admirable, et réparé avec le plus grand art’) and as 20 pouces (c. 54 cms.) high. Other versions of the model (some of which may of course be the same bronze) appeared in sales in 1812 (Maximilien Villers, 30 March 1812, lot 131), 1817 (Aléxis-Nicolas Pérignon, 10 December 1817, lot 136), 1821 (Varroc/Lafontaine, 28 May 1821, lot 219), and 1824 (the founder Feuchère, 29 November 1824, lot 5). The Feuchère example is the one that had been sold in 1812 from the Villers collection. The Belisarius in fact appeared in yet more sales, that have not hitherto been recorded in the literature on this bronze: 1816 (Lafontaine, 10 January 1816, lot 100, described as ‘a strong group with a greenish patina and on a gilt-bronze plinth’ (‘Un fort groupe, le repose de Bélisaire, avec son jeune conducteur, bronze vert antique, sur plinthe en bronze doré, par Chaudet’); 1835 (Théret and Bataillard, 15 December 1835, lot 156); 1842 (Baron Roger, 27 January 1842, lot 113, ‘Un très beau groupe en bronze: Bélisaire, par Chaudet, en l’an 2, signé sur socle, en bronze doré’; 1843 (Cabinet de M.C…, Seigneur and Schroth, 18 December 1843, lot 74, ‘Groupe de Bélisaire, par Chaudet (ce bronze est également le modèle’)’; 1865 (Duchesse de Berry, 8 May 1865, lot 340, described as ‘modern work’ (‘travail moderne’). The occurrences of this group seem therefore to be very largely concentrated into the first half of the nineteenth century, a period when the austere style of this strongly neo-classical composition would have more closely reflected contemporary tastes. Other than the sale of an example from the duchesse de Berry’s collection in 1865, no instances of sales of casts later in the century have yet come to light. It does also appear that very few casts were ever made, as is reflected in the rarity of surviving casts today; just four are known, including the one at the Argory. The finest is the cast now in the Metropolitan Museum, which is signed and dated ‘Year II’ in the revolutionary calendar, 22 September 1793-21 September 1794 (Janoray 2003; Draper 2007; French Bronzes 2009, no. 143). Exceptionally carefully chased, it has an ingenious steel mechanism within the base, that allows the sculpture to be turned. It is certainly one of the two or three casts of the Belisarius that were recorded as having been made during the sculptor’s lifetime and under his supervision. This cast is generally considered to be the one sold at the Paris Mont de Piété in 1803, and then again in 1817 in the Pérignon sale, which mentions a gilt-bronze base, which only the New York example has among surviving known versions. It could also be identifiable with the cast sold in 1816 and it is clearly the one sold from the collection of Baron Roger in 1842. Of the other surviving examples, one was recorded when it was lent to an exhibition in 1900, and is now in the château de Malmaison. It has been most recently described as a later nineteenth-century cast, as has the fourth version, which was offered at Sotheby’s London in 2003 (8 July, lot 167) and in 2005 (14 June, lot 69) and like the Malmaison version is signed ‘Chaudet fecit’ (‘Chaudet made this’). This bronze has reappeared recently on the art market at Bonham’s in London (Grand Tour sale, 14 July 2022, lot 47). The newly-identified cast at the Argory is a good bronze, well-modelled and finished, although a little inferior in its detailing and chasing to the New York version. The biggest substantive differences between the four versions appear to lie in Belisarius’s helmet and in the forms of the inscriptions and, in some cases, signatures. The lower part of the helmets in the New York and Malmaison bronzes has a decorative frieze of scrolling tendrils, whilst in the Argory and Bonham’s examples, this area of the helmet has studded decoration. The inscriptions vary greatly, but only in the Argory version, which is also the only one that is unsigned, is the exhortation ‘Give alms to Belisarius’ placed at the front of the bronze. In the other three it is on the side of the rectangular block on which Belisarius is seated, relating the bronze sculpture more clearly to David’s Belisarius, in which the block with its inscription is prominent at the right of the picture. In the Metropolitan bronze the inscription is misspelt; its signature with its date is simplified in the other two versions. Some entries in the early nineteenth-century sale catalogues are quite informative about the production of bronze casts during Chaudet’s lifetime. The entry for the Villers sale in 1812, two years after Chaudet’e early death, explained that ‘Copper being injurious to his health, he only executed himself two bronzes, of which this is the second. We urge art lovers not to confuse this admirable work with the manufactures of this sort that so often disappoint lesser connoisseurs’ (‘Le cuivre étant contraire à sa santé, il n’a exécuté que deux bronzes don’t celui-ci est le second. Nous prions les amateurs de ne point confondre cet ouvrage admirable avec cette manufacture qui trompe si souvent les médiocres connaisseurs’). This would appear to suggest that Chaudet, who indeed suffered a delicate constitution, directly supervised the production, by an unknown foundry, of two casts of the Belisarius, and may have done some of the chasing of those casts. At the 1824 sale of the bronze founder Lucien-François Feuchère, it was on the other hand implied that Chaudet supervised three casts, the example being sold being described as ‘one of the three that have been executed under the eyes of this talented artist’ ‘(‘un des trois qui ont été execute sous les yeux de cet habile artiste.’). Feuchère may of course himself have made further casts of the model. The other intriguing reference is in the 1843 sale of the collection of an anonymous Mr. C., in which it is stated that ‘this bronze is also the model’. We know therefore from these references that two or three casts of the Belisarius were made during the sculptor’s lifetime and under his supervision, also that an example existed that was believed to be the model. The only one of the casts known today that can certainly be identified as made under Chaudet’s supervision is the one in New York. It is most likely to have been the bronze version exhibited at the Salon in 1796. So far as the other three casts are concerned, it is not at all evident that a market for casts of this subject existed later in the century. It seems more likely that the casts at Malmaison and on the art market, which have more recently been described as dating from late in the nineteenth century, were in fact made in the years around 1800, and that the Argory cast was also made around the same time. Its modelling and chasing are very similar to that of the bronze sold at Bonham’s, and the style of the lettering of the main inscriptions on both bronzes also would indicate an earlier date. Thus, all the known casts of the model may have been made within the sculptor's lifetime. Some unresolved elements of the Argory cast suggest that it could be a prototype, and thus one of the earliest of the casts to have been produced, possibly even the one identified in the 1843 sale as ‘the model’ and therefore the first version of all. The placing of the inscription on the front might have been thought to have been considered too obvious, even sentimentalising, prompting its move to the side for the other three versions. The large circular base, which is undecorated, is unusual in the context of French bronzes in these decades and appears to serve no obvious purpose. It is just conceivable that it could have served as some sort of model for the planning of the New York version, with its base containing the mechanism for turning the bronze. Finally, the lack of the artist's signature might suggest this cast, with its unusual base, was put aside. Whatever its precise status, the bronze group of Belisarius and his guide at the Argory is an outstanding example of French neo-classical sculpture and bears poignant witness to the revolutionary times in which it was made. Jeremy Warren June 2022

Provenance

By descent; Walter McGeough Bond (1908-86), by whom given to the National Trust in 1979.

Marks and inscriptions

On front of base:: DATE OBOLUM BELISARIO [Give alms to Belisarius]

Makers and roles

Antoine-Denis Chaudet (Paris 1763 - Paris 1810), sculptor

References

Hubert 1959: Gérard Hubert, ‘Notes sur deux oeuvres retrouvées du sculpteur Chaudet’, Nouvelles Archives de l’Art français, Vol. 22 (1950-1957), published Paris 1959, pp. 287-92. New York 1968: The French Bronze,1500-1800, M. Knoedler & Co., New York 1968, no. 93. Janoray 2003: Charles Janoray, Chaudet’s Belisarius: An Example of Virtue, New York 2003 Draper 2007: James David Draper, ‘Chaudet’s Belisarius and a borrowing from David’ in Geneviève Bresc-Bautier and Pierre-Yves Le Pogam (eds.), La sculpture en Occident. Études offertes à Jean-René Gaborit, Dijon 2007, pp. 226-231. French Bronzes 2009: G. Bresc-Bautier, G. Scherf and J. D. Draper, eds., Cast in Bronze. French Sculpture from Renaissance to Revolution, exh. cat. (Musée du Louvre, Paris/MMA, New York), Paris 2009, pp. 492-93, no. 143.