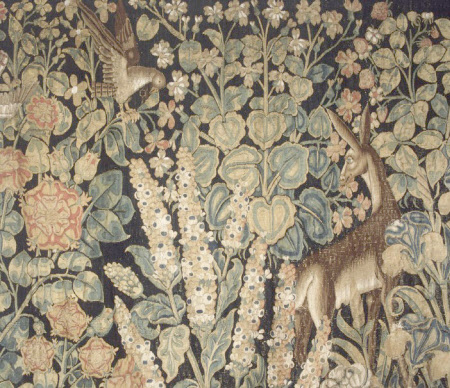

Verdure with Roses

Flemish

Category

Tapestries

Date

circa 1510 - circa 1540

Materials

Tapestry, wool, 5 warps per cm

Measurements

2580 x 2630 mm

Order this imageCollection

Cotehele, Cornwall

NT 348313

Summary

Tapestry, wool and silk, 5 warps per cm, Verdure with Roses, Southern Netherlands, c. 1510-1540. A rectangular tapestry with a large section cut out from the centre to accommodate a rounded door frame. A variety of different flowering plants are arranged on a dark blue ground with animals and birds among the leaves, larger plants growing towards the bottom and smaller ones at the top. To the left of the door frame is a large clump of fox-gloves with pale flowers, and to the right a chrysanthemum bush with red and yellow flowers. Above are a variety of smaller plants including irises, violets, strawberries and periwinkles. At the sides two oversized rose bushes with large, stylized red and white flowers spread their branches almost the entire height of the tapestry. In the centre of the tapestry over the doorway a brown hind stands among the flowers with her back to us, and to the right of the door by the chrysanthemum a large griffin is seen in profile, with a curling tongue, eagle’s wings and lion’s feet. Brown game birds appear to the left and at the top, and there are two snails and a dragonfly on the lower leaves of the chrysanthemum. Two sections almost certainly from elsewhere within the same tapestry have been sewn on at the top right-hand corner. There is a narrow red and white band at the top which may or may not be original to the main field, but no borders on the other edges.

Full description

This fragment is the remains of a larger panel which would have been totally covered with flowering plants, and may have included additional decorative or heraldic motifs. All the small plants at the top end uniformly before the upper edge, indicating that this is the original upper edge of the main field, but it there is no indication of how far the design originally extended at the sides or the bottom. The narrow band of red and white at the top may be all that remains of a wider border. The dark blue ground may originally have been green. The overall design, composed of an accretion of individual plants arranged on a plain dark ground, is of a type sometimes referred to as ‘leaf and flower’ verdures (Franses 2005, p. 21). This style of verdure emerged at the beginning of the sixteenth century, and can be seen as a development from the so-called ‘millefleurs’ tapestries decorated with thousands of tiny flowers that were popular in the fifteenth century. In the tapestry at Cotehele the plants are larger, they overlap more frequently, and the scale of those at the bottom, and the roses at the edges, is exaggerated, giving a greater sense of vitality and spatial depth than the earlier ‘millefleurs’ designs. Leaf and Flower verdures emerged in the second decade of the sixteenth century, at around the same time as the so-called ‘large leaf verdures’ decorated with giant leaves covering the entire surface of the tapestry. The new genres of verdure have been linked to a growing interest in the natural world and in botany, spurred in part by discoveries in the New World in the sixteenth century, and the exotic plants and animals to be seen there (Wingfield Digby and Hefford 1980, pp. 54-55; Cavallo 1993, pp. 586-93; 600-07). Whilst the plants seen in large leaf verdures are often fanciful, all of the plants in the present tapestry are fairly common. Their forms, although exaggerated in scale so that the plants towards the bottom are larger, are fairly naturalistic, and recall the illustrations to herbals, or botanical texts, that became increasingly popular in the late fifteenth century. The illustrations to these books usually included the whole plant exhibiting roots, leaves, and flowers in bud and in bloom. The hind, game birds and snails in the tapestry reflect the usual inhabitants of a European forest, and suggest the pursuit of hunting; the griffin on the other hand is typical of the often fantastical beasts that inhabit verdure and giant leaf tapestries of the sixteenth century. In some cases these beast are interpreted as having a religious or moral significance. The griffin, with the head, wings and claws of an eagle and the body and back legs of a lion, was sometimes used as a symbol of Christ’s dual nature, and it was also a common heraldic beast, signifying the watchfulness of an eagle and the courage of a lion. A possible heraldic meaning to the tapestry is further suggested by the two rose bushes whose blooms, often seen face-on, are extremely large and noticeably symmetrical in design, in striking contrast to the naturalistic depiction of the other plants and flowers. In addition, although they are now faded, the flowers are clearly red and have white centres, which recalls the Tudor Rose adopted as a badge by Henry VII to symbolise the union of the houses of York and Lancaster, and also used by his son Henry VIII. It is possible that the roses were intended as a statement of loyalty to the Tudor monarchy; however similar stylized roses do occasionally appear in sixteenth-century verdures with no heraldic meaning. The incomplete state of the tapestry today makes it impossible to be sure as to its original iconography. It was not uncommon for tapestries of this sort to include both overt and hidden heraldic devices: notable examples include an armorial tapestry made for Margaret of Austria in Enghien in c. 1524-28 (Delmarcel 1980, pp. 18-19) and a series of eight armorial tapestries of comparable style to the panel at Cotehele woven by Willem de Pannemaker for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in c. 1540-55 (Hartkamp-Jonxis and Smit 2004, pp. 75-79). Other examples include non-heraldic devices, sometimes religious scenes, sometimes small narrative cartouches, and sometimes simply animals and birds (for further examples see Delmarcel 1980, pp. 18-49; Franses 2005, pp. 56-62). The tapestry bears no marks indicating its place of manufacture. Similar ‘leaf and flower’ tapestries were produced in a number of different weaving centres in the Southern Netherlands in the first half of the sixteenth century. A relatively large number have survived which bear the mark of the town of Enghien (Delmarcel 1980, pp. 18-49), and there are also instances of similar tapestries being produced in Brussels and elsewhere. (Helen Wyld, 2010)

Provenance

Left at Cotehele when the property was accepted in lieu of tax from Kenelm, 6th Earl of Mount Edgcumbe (1873-1965) and transferred to the National Trust in 1947; amongst the contents accepted in lieu of estate duty by H M treasury and transferred to the National Trust in 1974.

Credit line

Cotehele House, The Edgcumbe Collection (The National Trust)

Makers and roles

Flemish, workshop

References

Brosens, 2008: Koenraad Brosens, European Tapestries in the Art Institute of Chicago, New Haven and London 2008 Franses, 2005: Simon Franses, Giant Leaf Tapestries of the Renaissance: 1500-1600, exh. cat., S Franses, New York 2005 Hartkamp-Jonxis and Smit, 2004: Ebeltje Hartkamp-Jonxis and Hille Smit, European Tapestries in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 2004 Cavallo, 1993: Adolpho S Cavallo, Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1993 Delmarcel, 1980: Guy Delmarcel, Tapisseries Anciennes d’Engien, Mons 1980 D'Hulst, 1967: R A d’Hulst, Flemish tapestries from the Fifteenth to the 18th Centuries, Brussels 1967, pp. 257-262 Wingfield Digby and Hefford, 1980: George Wingfield Digby and Wendy Hefford, Victoria and Albert Museum: The Tapestry Collection, Medieval and Renaissance, London 1980