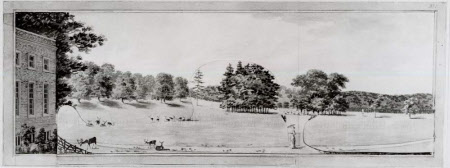

View from the north of the house at Wimpole, Cambridgeshire, Plate I from the Wimpole Red Book

Humphry Repton (1752 - 1818)

Category

Architecture / Drawings

Date

1801

Materials

Watercolour

Measurements

214 x 547 mm

Order this imageCollection

Wimpole, Cambridgeshire

NT 206226.1

Caption

Humphrey Repton was employed by the 3rd Earl of Hardwicke to make improvements to the park. He produced one of his famous Red Books for the 3rd Earl, a series of before and after drawings to show how the parkland would be transformed. This watercolour is a view from the North front of the Hall looking towards the Gothic Tower, proposing the addition of a flower garden and railings.

Summary

Humphry Repton (Bury St Edmunds 1752 – Romford 1818), View from the north of the house at Wimpole, Cambridgeshire, with flap, 1801, inscribed top right 'No. I', watercolour (214 x 547mm).

Full description

The first plate in the Red Book suggests a dramatic change to the north park as viewed from the house. In the foreground Repton proposes that a flower garden, bounded by railings, should be created within the arms of the projecting library and laundry wings. Repton explains in the accompanying text why he felt it necessary to introduce this proto-gardenesque buffer between house and park: ‘It is called natural, but to me it has ever appeared unnatural that a palace should rise immediately out of a sheep pasture’. This view represents a theoretical volte-face for in the previous decade Repton had created exactly that relationship at Welbeck Abbey, Nottinghamshire, and at Pretwood, Staffordshire. This change of heart flowed directly from the barbs that had been fired in his direction during the debate of the so-called ‘Picturesque Controversy’ that was triggered in 1794 by the publication of Sir Uvedale Price’s (1747—1829) 'An Essay on the Picturesque' and Richard Payne Knight’s (1750—1824) 'The Landscape: A Didactic Poem'. Repton notes in his memoir that Payne and Knight ‘pretended to a new system of taste, in opposition to that introduced by Lancelot Brown, of whom I was accused of being the servile follower’. Repton was eager to flatter these two idealogues, to embrace the newly articulated principles of the Picturesque, and to demonstrate that there was clear blue water between his work and Brown’s legacy, but he continued to make recommendations that were Brownian in character until the turn of the century. The proposals set out in the Wimpole Red Book appear to mark an important turning point, at which Repton’s practice finally accords with his theoretical stance. In his scheme for the flower garden to the north of the house he adopts the unequivocally formal approach that he had previously studiously avoided, and, perhaps encouraged by his new partnership with John Adey whose association with John Nash (1752—1835) had ended in the previous year, a new interest in antiquarianism is also signalled. Repton proposes in the Wimpole Red Book that an iron rail ‘which does not attempt to be concealed’ should enclose the garden because, he felt, ‘it would surely be unnatural to see deer and flowering shrubs without any line of separation between them’, and suggests in this watercolour that the screen should be articulated by regularly spaced urns. Repton’s flower terrace, with its railings, piers and urns was not in fact realised. A marginal note in the Red Book, presumably written by Repton’s patron, reads: ‘Expensive and the appearance doubtful’. Robert Withers’s survey (NT 206295) shows that the line of the present railings screen, placed further to the north than Repton had suggested, was established by 1815. The present railings and piers bear all the hallmarks of H.E. Kendall’s work of the mid-nineteenth century. In the middle ground, beyond the screen intended to separate garden from park, Repton could comfortably revert to a Brownian stratagem. He suggests sweeping away the clump of trees which formed the western side of Robert Greening’s ‘eyetrap’. Repton felt that the axial view of the Gothic folly on Johnson’s Hill—symmetrically framed by these trees—was somewhat contrived. By excising one side of the frame, a more natural effect could be produced. The folly itself, though he could never have dared to recommend its removal, may have offended Repton’s sensibilities. Despite describing it as ‘one of the best of its kind extant’ (perhaps faint praise), more often than not he railed against such structures. In his didactic Preface to Observations Repton sets out ten ‘Objections’ of which ‘No.9’ reads: ‘sham churches, sham ruins, sham bridges and everthing which appears what it is not, disgusts when the trick is discovered’ (p. 14). In the Wimpole Red Book he recommends introducing a covered seat in order ‘to lead the eye away from the Tower which perhaps at present attracts too much of the attention’. Repton banishes other vestiges of formality such as the statuary to either side of Greening’s clump with the lifting of the improving flap. Repton also suggests converting the fields to the north-east into grazed pasture land. In the ‘before’ view these are, somewhat misleadingly, shown as scrub. Because of the lie of the land at Wimpole it is not possible, at least from ground level, to see the lakes from the north side of the house. Repton considered this to be a fault whose remedy might be provided by mooring a tall-masted boat on Brown’s lower lake, its sails and pennant, visible in the ‘after’ view at far right, would at least signal the presence of the lakes. This is a typically Reptonian idea; elsewhere he proposed, for example, that the location of a woodsman’s cottage might be identified in the landscape by a wisp of smoke produced by a constantly tended fire. Repton’s accompanying text reads: The principal apartments look towards the north where / the view was formerly confined by a regular / amphitheatre of trees and shrubs, these have been in a / great measure all removed; except a few sickly exotics / which mark the danger of partially removing trees that / have long protected each other; but tho’ the formal / semicircle is removed, yet there remain two / corresponding heavy clumps, between which is shewn / the building on the hill which, I suppose was at one / time the only object to be seen beyond this formal / inclosure. This building which is one of the best of its / kind extant, is now only seen thro’ this narrow gap / from the centre of the house, while a glimpse of the / distant hill and fine shape of ground on which it / stands, suggests the propriety of removing one of these / clumps and loosening the other. Catalogue entry adapted from David Adshead, Wimpole Architectural drawings and topographical views, The National Trust, 2007.

Provenance

Philip Yorke, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke, KG, MP, FRS, FSA, (1757–1834); bequeathed by Elsie Kipling, Mrs George Bambridge (1896 – 1976), daughter of Rudyard Kipling, to the National Trust together with Wimpole Hall, all its contents and an estate of 3000 acres.

Marks and inscriptions

Top right: No: 1

Makers and roles

Humphry Repton (1752 - 1818), landscape architect

References

Adshead 2007: David Adshead, Wimpole Architectural drawings and topographical views, The National Trust, 2007, p.100, no.192 Jackson-Stops, 1979: Gervase Jackson-Stops. Wimpole Hall: Cambridgeshire. [London]: National Trust, 1979., p.61 Stroud 1979: Dorothy Stroud, “The charms of natural landscape. The parks and gardens at Wimpole.” Country Life CLXVI, no 4288, 13 September 1979, pp.758-62, figs. 9 & 10