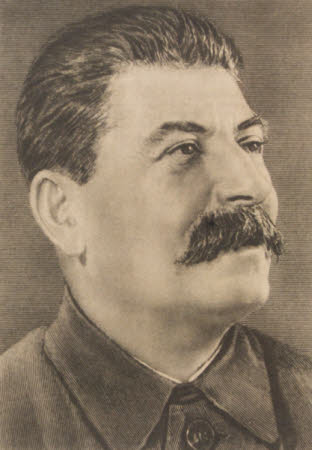

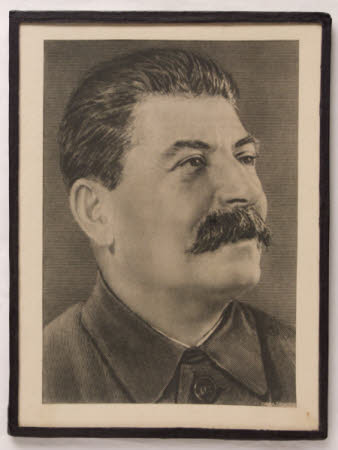

Joseph Stalin (1879-1953)

Category

Photographs

Date

circa 1931

Materials

Paper

Measurements

8 ins (h)6 ins (w)

Order this imageCollection

Shaw's Corner, Hertfordshire

NT 1274649

Summary

Monochromatic print after a photograph of Joseph Stalin (1878 – 1953) produced in c.1931. Head and shoulders portrait, wears a jacket buttoned to the neck. Glazed; black passe partout frame.

Full description

Monochromatic print after a photograph of Joseph Stalin (1878 – 1953) produced in c.1931. Head and shoulders portrait, wears a jacket buttoned to the neck. Glazed; black passe partout frame. Bernard Shaw admired the Soviet Union dictator Joseph Stalin, besides the Russian revolutionaries Vladimir Lenin and Felix Dzerzhinskii, owing to the work they had done in constructing the new Soviet society. Both Shaw and Charlotte invested financially in the USSR. Images of all three men were displayed on the dining room mantelpiece at Shaw’s Corner by Shaw at some point after 1930 (probably during the 1940s). Shaw had been a Fabian Socialist since 1884 and hence believed in achieving social reform to eradicate inequality by gradual and non-violent means, however disillusionment with the Labour Party during the 1930s and 40s saw him turn back towards a more revolutionary, “Communistic” approach he associated with William Morris and the Soviet Union. In 1932 Shaw wrote to his friend Emery Walker: “Morris was right after all. The Fabian parliamentary program was a very plausible one; but, as Macdonald has found, parliament and the party system is no more capable of establishing Communism than two donkeys pulling different ways.” (Shaw to Emery Walker, 25 January 1932, Collected Letters vol.4, 274). Shaw described what he termed “the success of the Russian experiment” in a lecture he presented to the Fabian Society on 26 November 1931. In the lecture he remarked: “I have always liked to call myself a Communist… I like the name just as William Morris liked the name.” (Shaw, in L. Hubenka, ed. Bernard Shaw Practical Politics, 212-13). The talk was part of a series “Capitalism in Dissolution: What Next?” In an earlier lecture presented to the Independent Labour Party in August 1931, Shaw declared that: “The success of the Five Year Plan is the only hope of the world.” (Shaw, The Only Hope of the World, 5 August 1931, in Dan Laurence, ed., Bernard Shaw: Platform and Pulpit, 222). Shaw seemed to find in the USSR the leadership he perceived to be lacking in Western democracies. He felt that as a leader Stalin had “extraordinary military ability and force of character,” and that his policies would make people become “really responsible citizens”. Shaw had visited the Soviet Union in July 1931, when he accompanied Nancy Astor and others to Moscow. Shaw visited Lenin’s tomb, and also met important cultural figures including the theatre director Konstantin Stanislavsky and writer Maxim Gorky. An interview with Stalin himself on 29th July lasted nearly two hours, and he later recalled: “I expected to see a Russian working man and found a Georgian gentleman.” Many left-wing British intellectuals supported Stalin’s domestic policies during the 1930s and 40s, but none more so than Shaw. Some critics have believed that “Shaw’s age had brought about a serious decline in his judgment.” (David Nathan, “Failure of An Elderly Gentleman”, Shaw and Politics, SHAW Vol.11, 1991, 236). Indisputably Shaw’s inability to question the myth of Stalin as a great leader, his lack of commentary on the atrocities committed by Stalin, and his lack of critique of the propaganda that portrayed the Soviet Union as a socialist utopia, was his greatest failing. Shaw was always a highly controversial and contradictory figure. Stalin’s portrait is on the mantelpiece in the dining-room, placed next to those of Lenin and Dzerzhinskii (see NT1274648; and NT1274647). Adjacent images of Henrik Ibsen and Mahatma Gandhi however represent a more humanitarian outlook that was staged by Shaw to deliberately challenge the Soviet presence.

Provenance

The Shaw Collection. The house and contents were bequeathed to the National Trust by George Bernard Shaw in 1950, together with Shaw's photographic archive.

Marks and inscriptions

At bottom right in Russian capitals "GRAV A TROITSKI"