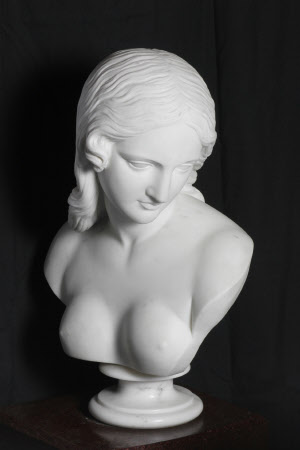

Bust of Eve

Edward Hodges Baily (Bristol 1788 - London 1867)

Category

Art / Sculpture

Date

Unknown

Materials

Marble

Measurements

560 mm (H)940 mm (H)457 mm (W)330 mm (D)

Place of origin

London

Order this imageCollection

Cragside, Northumberland

NT 1231039.1

Summary

Sculpture, marble; Head of Eve; Edward Hodges Baily (1788-1867); c. 1840-60. A head of a young girl, a version of the head of Eve in one of Baily’s most successful works, the Eve at the Fountain, made in 1822 and now in Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

Full description

An ideal portrait bust of a young woman, her arms truncated and her breasts exposed, head turned sharply to her left. She has long and thick hair, a curl near her right ear. Mounted on a turned white marble socle. The head is a version of Edward Hodges Baily’s Eve at the Fountain, one of the most popular ideal sculptures in Britain during the first half of the nineteenth century, which depicted Eve in an episode from Milton’s Paradise Lost. Edward Hodges Baily was a successful sculptor who had a long career running throughout virtually the whole of the first half of the nineteenth century. He is best-remembered today for his colossal statue of Lord Nelson atop Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, London, although the figure was criticised at the time of its installation. In his lifetime, his ideal figures were especially highly regarded, above all the Eve at the Fountain, which overall turned out to be Baily’s most successful work. He made many portrait busts, such as the portrait bust of Armorer Donkin also at Cragside (NT 1231033) and exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy. Baily was also active throughout his career as a designer for silver manufacturers such as Rundell and Bridge. The Eve at the Fountain in fact had its genesis in a model of a small reclining figure of a woman, made to surmount a bottle cooler produced by Rundell and Bridge in a number of versions from around 1821 onwards (Christopher Hartop, ed., Royal Goldsmiths. The Art of Rundell and Bridge 1797-1843, London 2005, pp. 108-09, fig. 104). Baily’s small clay model is today in Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, as is the prime marble version of the Eve at the Fountain. Baily exhibited a sketch for his larger statue at the Royal Academy in 1819 and in 1820 a full-size version in plaster, which may well be the version today in the Victoria & Albert Museum (Inv. A.3-2000. Diane Bilbey and Marjorie Trusted, British Sculpture 1470 to 2000. A Concise Catalogue of the Collection in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2000, no. 262). In 1822, Baily showed at the RA the marble version that would assure the sculptor’s fame, under the title Eve at the Fountain, referring to a passage in Book IV of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, in which Eve describes to Adam her first moments of experiencing life, as she gazes into water to see her reflection: As I bent down to look, just opposite, A shape within the wat’ry gleam appear’d, Bending to look on me: I started back, It started back; but pleas’d, I soon return’d Pleas’d it return’d as soon with answering looks Of sympathy and love. The sculpture was very warmly received when it was exhibited at the RA and again in 1823 at the British Exhibition, on which occasion Baily was awarded a prize of 100 guineas for the ‘best specimen of native sculpture.’ Nevertheless the work failed to sell and it was not until 1826 that the Bristol Institution had its arm twisted by the sculptor (who was from Bristol) to purchase the sculpture, raising the price of £630 by subscription. In the course of the 1820s and 1830s, the fame of the sculpture grew, with Baily being commissioned in the course of his career to make at least five copies, one of which, dated 1845, is today in the collection of the Ny Carlsberg Glypotek in Copenhagen. He also gave a plaster version to the Athenaeum Club in London in 1830, disposed of in the early 20th century and now lost. In the early 1840s, Baily was commissioned by his major patron Joseph Neeld to make a new statue of Eve, this time entitled Eve listening to the Voice. The marble is today in the Victoria & Albert Museum (Bilbey and Trusted, British Sculpture 1470 to 2000, no. 266). This second sculpture attests to the huge popularity and success of the earlier sculpture, in that it is all but identical in conception to the Eve at the Fountain, except that Eve’s head is turned to her right. The Eve at the Fountain was one of eighteen works included in Illustrations of Modern Sculpture, a book published in 1832 by Thomas Kibble Hervey celebrating the best contemporary sculptures. To judge from the laudatory poems that accompanied Hervey’s text, contemporary audiences responded in particular to the subject’s perceived pure, fresh and innocent beauty, even though her absorption in her own appearance in the water’s reflection could be said to prefigure her temptation and fall. In 1848, the Art Union summed up the enthusiasm for Baily’s creation: ‘No example of our school of sculpture has attained a wider range of popularity, or has merited a higher claim to what it enjoys, than this exquisitely beautiful figure, in which the purity and chastity of the sculptor's style is pre-eminently manifested.’ (I November 1848, p. 320). Samuel Hall, in another compendium on modern sculpture published in 1854, suggested that Baily’s Eve at the Fountain was ‘universally popular.. they must be few indeed who are not intimately acquainted with it. In every possible material, and in an infinite variety of sizes, it has been copied and dispersed abroad, to an extent, perhaps, far exceeding that of any sculptured work.’ (S.C. Hall. Ed, The Gallery of Modern Sculpture, London 1854). Among the many copies that were made, Baily’s workshop produced reduced scale plaster statuettes in large numbers, as well as busts such as the one now at Cragside. There is more decorum in the original sculpture, in which Eve’s left arm covers and at least partly conceals her breasts, than in these truncated armless versions, in which they are fully exposed. Other marble bust versions recorded include one formerly in the collection of the Dukes of Newcastle and others sold at Sotheby’s (20 November 1997, lot 125; Old Master Sculpture & Works of Art, London, 2 July 2019, lot 123). The Illustrated London News claimed in its obituary of Edward Hodges Baily that some 20,000 casts had been manufactured. This figure might seem improbably high, but a note by his son-in-law Joseph Riddel, among the collection of material he gathered in the early 1880s for a biography of Baily that never materialised, recorded a note in ‘Mr Baily’s Cash-Book, “June 28 1856. Messrs Minton for Statuette of Eve listening: Price £50 (5000 copies of the head are said to have been sold in the U[nited] states”’. (British Library, Add.Ms. 28678, fol. 89). Strangely, the model does not appear in Minton’s published lists of their Parian products. However, the Parian-ware busts entitled ‘Flora’, made in around 1875 by Robinson and Leadbeater, were derived from Baily’s bust-length versions of his Eve; one version was clothed, the other naked and very similar to the Cragside bust, except that the girl has a wreath of flowers in her hair (Paul Atterbury, The Parian Phenomenon. A Survey of Victorian Parian Porcelain Statuary & Busts, Shepton Beauchamp 1989, p. 228, fig. 737). Baily’s Eve at the Fountain was also popular in France, where the Barbedienne foundry offered from 1845 onwards bronze casts (Florence Rionnet, Les Bronzes Barbedienne. L’oeuvre d’une dynastie de fondeurs, Paris 2016, ct. no. 1275). Jeremy Warren March 2022

Provenance

Armstrong collection. Transferred by the Treasury to The National Trust in 1977 via the National Land Fund, aided by 3rd Baron Armstrong of Bamburgh and Cragside (1919 - 1987).

Makers and roles

Edward Hodges Baily (Bristol 1788 - London 1867), sculptor

References

Bilbey and Trusted 2002: Diane Bilbey and Marjorie Trusted, British Sculpture 1470 to 2000, A Concise Catalogue of the Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2002, no. 262. Jordan 2006: Caroline Jordan, ‘”The very spirit of purity and chastity”: Eve at the Fountain by Edward Hodges Baily’, The Sculpture Journal, 15.1 (2006), pp. 19-35., pp. 29-31, fig. 11. Roscoe 2009: I. Roscoe, E. Hardy and M. G. Sullivan, A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain 1660-1851, New Haven and Yale 2009, p. 59, no. 119