There are around 6,000 sculptures in the collections of the National Trust. They come in every shape and size, from enormous monumental marble statues to miniature carvings in ivory. It is an internationally important collection, with single masterpieces, as well as significant groups of works by individual artists.

Greek and Roman sculpture

Petworth holds one of the most important private collections of antique sculpture to remain intact. Amassed by Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont (1710–1763), a highlight of the collection is a marble head of Aphrodite sculpted in Greece in the 4th century BCE. Known as the Leconfield Head, it was attributed in 1888 to the enigmatic Greek sculptor Praxiteles. Today the marble is largely accepted as a high-quality Attic original of the Praxitelean School. It was acquired on behalf of the 2nd Earl in 1755 by the Scottish painter Gavin Hamilton (1723–98) who is famed for his prolific excavation and export of antique marbles to the British aristocracy. The head was displayed by the 2nd Earl in a custom-built antiquities gallery designed by the Palladian architect Matthew Brettingham the Elder (1699–1769). It was later moved to the Red Room by his son, the 3rd Earl.

A group of antique busts, collected on a Grand Tour of Italy by William Holbech (d. 1771), are unified in an inventive Palladian scheme of decoration for the hall of his family seat, Farnborough. Busts of emperors, goddesses, famous Roman men and women are set within bespoke oval niches as a procession, running around the periphery of the room above mantelpieces and doorways. This dynamic arrangement is rarely found in other country houses and was conceived a full decade before similar schemes were seen at Petworth and Holkham.

An interior view of Farnborough Hall, Warwickshire

Discovered not in Rome but in Egypt, a rare basalt bust thought to represent Cleopatra’s lover Mark Antony can be seen at Kingston Lacy. The bust was found in Canopus, near Alexandria, in around 1780, and its distinctive style has led historians to believe that it was produced by Greek artists working there in the late 1st century BC. Today it presides over a small but wide-ranging collection of Egyptian sculptures and antiquities assembled by William Bankes (1786-1855).

Acquired more than a century later than William Bankes's Egyptian collection is the exceptional group of Roman sarcophagi collected by William Waldorf Astor (1848-1919) for his new home at Cliveden. Displayed on the forecourt lawns are eight of Lord Astor’s sarcophagi, including the unique Theseus Sarcophagus found in 1833 at Castel Giubileo, the ancient site of Fidenae. Unusually this tomb commemorates a mother and son rather than a husband and wife, and is dedicated by ‘Valeria’ to her seventeen-year-old son ‘Artemidoros’, figured as Theseus.

Bronzes

While the ancient Greeks and Romans had a long history of making bronze sculptures, the art was revived during the Renaissance. Sculptures in stone were generally too heavy and bulky to be handled, but small bronze sculptures, easily reproduced, offered a more tactile and intimate experience.

One of the most popular bronze models is the celebrated figure of Mercury by Giambologna (1529-1608). He created four versions of Mercury from 1563, including the Medici Mercury, now in the Bargello, Florence. There are many 18th- and 19th-century copies of this famous work, including a bronze statuette at Stourhead and a monumental lead and bronze version at Dyrham Park, attributed to John Nost I (c.1665-1710).

18th-century sculpture

Many National Trust collections are defined by the Grand Tour, among them Kedleston Hall and Osterley Park, both of which feature interiors designed by Robert Adam (1728-92) in which originals or copies of Roman sculptures become integral parts of the neo-classical decorative schemes.

The Marble Hall at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire

The entrance hall at Osterley, London

Italian artists like Giovanni (c.1745-1805) and Giacomo Zoffoli (c.1735-85) made a good living by producing large and small-scale copies of famous antiquities for Grand Tourists, such as the Zoffoli bronze mantelpiece ornaments at Saltram depicting antiquities like the Capitoline Marcus Aurelius and the Medici and Borghese Vases.

The early decades of the 1700s saw the development in Britain of native schools of painting and sculpture, even though many of the sculptors who found success in this country in fact came from abroad. Among the greatest of this new generation of sculptors was John Michael Rysbrack (1694-1770), originally from Antwerp, whose powerful Baroque style and gifts as a portraitist won him many patrons.

The National Trust’s remarkable assemblage of sculptures by and after Rysbrack is arguably the most significant anywhere. The greatest concentration of works is at Stourhead where there are monumental statues after the antique, portrait busts and terracotta reliefs. Rysbrack’s seven highly individual sculptures of Norse or Saxon deities left Stowe long ago, but one of them, the statue of the god Tīw or Tyr is now part of the collection at Anglesey Abbey. Rysbrack’s brilliant representation of a goat in terracotta can also be seen there. Although much of the contents of Clandon Park were destroyed in the disastrous fire in 2015, the two great chimneypieces in the Marble Hall with marble reliefs by Rysbrack were fortunately unharmed.

Garden sculpture

Gardens have long been status symbols for their aristocratic owners and sculpture has played an incredibly important part in their design, offering owners the means to display their classical understanding and artistic taste.

While bronze was an expensive medium for statuary and more suited to smaller scale statuettes, lead became an increasingly popular medium for garden statuary from the end of the 17th century. Easy to cast, sculptors could produce multiple copies from a single mould.

For its breadth and quality, the National Trust holds one of the most important collections of British late 17th- and 18th-century garden sculptures in lead. The principal makers of these sculptures, often derived from antique models or from ‘modern’ acknowledged masterpieces such as Giambologna’s Samson and the Philistine, were John Nost I, Andrew Carpenter (c.1677-1737) and John Cheere (1709-87). The same models can be found in different National Trust houses, for example casts after the Samson and the Philistine are at Anglesey Abbey, Seaton Delaval and Wimpole Hall. Other significant groups of lead sculptures are at Fountains and Studley Royal, Kedleston and Lyme Hall.

Stowe

The landscape garden at Stowe is one of the most remarkable legacies of Georgian England. Created in the grounds of his family home by Richard Temple, Viscount Cobham (1669-1749), Stowe’s range of garden buildings, waterworks and sculpture physically reflect Cobham’s personal and hugely influential network of political affiliations.

The Temple of British Worthies, for example, is a highly significant political scheme expressed through a building and its sculpture. The temple, a curved exedra, contains sixteen busts of ‘British Worthies’ by Rysbrack and Peter Scheemakers (1691-1781): sculptures of great men specifically chosen by Cobham for their actions, thoughts and ideas. The busts fulfilled a political agenda, representing the Whig ideas of Cobham and his circle.

Standing opposite The Temple of British Worthies is the Temple of Ancient Virtue, a circular domed building with a colonnade of Doric columns. Inside are four niches which contain statues of Homer, Socrates, Lycurgas and Epaminondas (all plaster casts of the original Portland Stone statues produced by Scheemakers). These figures were chosen for their roles as greatest poet, philosopher, law-giver and general of ancient Greece. They stood as the epitome of ancient virtue looked up to by the British Worthies.

The Temple of British Worthies

Stowe Landscape Gardens, Buckinghamshire

French 18th-century sculpture

There can hardly be a better place to see the exquisite taste of 18th-century France than in the sumptuous interiors of Waddesdon Manor, home of Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild (1839-98). Works by or after many of the greatest 18th-century French sculptors may be admired there, including a series of terracotta groups by Clodion (Claude Michel, 1738-1814).

Sculpture was an important element of the French interior, with sculptural figures often being incorporated into clocks, candlesticks and silver objects. Famous larger sculptures would often be reproduced on a smaller scale in marble or in bronze, such as the powerful figure of Mars, god of war at Erddig, attributed to Sébastien-Antoine Slodtz (1695-1754).

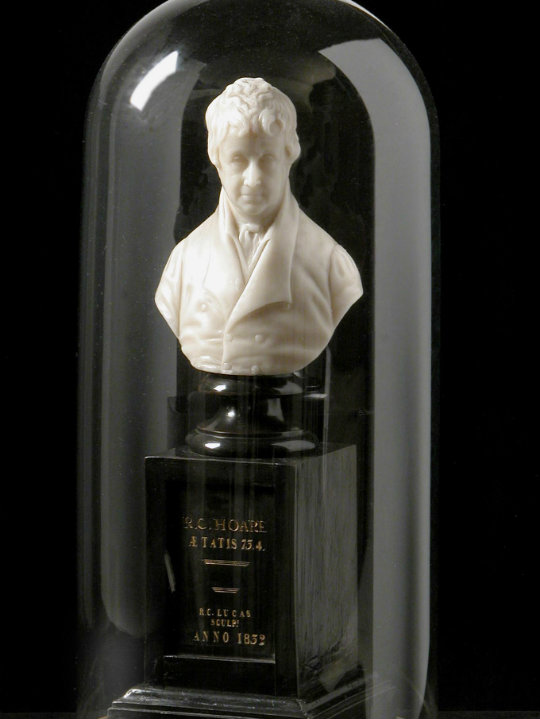

18th- and 19th-century British portraits

Sculpted portraits form a large and important part of the National Trust’s sculpture collection, ranging from small-scale cameos and medals, to larger portraits in relief and numerous plaster, terracotta and marble busts and statues. The National Trust has works by many of the leading 18th- and 19th-century portrait sculptors, including John Michael Rysbrack, Joseph Nollekens (1737-1823), Lorenzo Bartolini (1777-1850), Richard Westmacott (1775-1856), Francis Chantrey (1781-1841), William Behnes (1795-1864), Lawrence MacDonald (1799-1878) and Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834-1890).

As well as commissioning a sculpted portrait of oneself, one’s family or friends, it was also common to display busts of contemporary politicians, royalty or esteemed public figures within the country house setting. These busts were a prominent way in which to display political allegiances or express admiration for certain public figures, such as Viscount Cobham’s scheme at Stowe. Joseph Nollekens’ studio was particularly successful in selling multiple copies of his busts of famous figures.

Wax portraits

Wax has been an important medium for sculptors, and was used in particular for portrait miniatures in the 18th and 19th centuries. Wax portraits were either sculpted in relief, or in bust form; they could be in cream wax, or tinted, usually in pink, or polychrome. Many sculptors who specialised in wax were itinerant artists, who would visit country houses to take likenesses. Although a much cheaper form of portraiture than a large bust in marble, wax portraits were extremely popular amongst the nobility, and indeed royalty. Their appeal lay in the incredible verisimilitude that could be achieved, as well as the speed with which a portrait could be produced. Wax portraits could also be cast a number of times, therefore enabling those commissioning a portrait to have multiple versions to give to friends and family

Although wax modellers were highly skilled artists, the medium also appealed to amateur artists, in particular women. One such example is a wax miniature of a young boy, Henry Villiers Parker, Viscount Boringdon at Osterley Park. The portrait was modelled by his step-mother, Frances Parker, Countess of Morley (1782-1857) who lived at Saltram in Devon. When Henry died tragically at the age of 11, his image took on a great significance and was cast a number of times. The version at Osterley was given to Sarah Sophia Child Villiers, Countess of Jersey (1785-1867), the boy’s maternal aunt.

One of the most well-known and successful wax modellers of the late 18th century was the Irish artist Samuel Percy (1750-1820). Percy was particularly known for his polychrome wax portraits in high relief. A good example of such a work by Percy is his portrait of Joshua McGeough of Drumsill (1747–1817) at The Argory in Northern Ireland.

Neo-classical sculpture

Neo-classical sculpture is epitomised by the work of Antonio Canova (1757-1822), whose sculptures can be traced across National Trust collections, in originals and copies. In his statue Amorino at Anglesey Abbey, Canova captures the tenderness of Cupid, the god of love, as a young boy. It was originally commissioned by Colonel John Campbell, later Baron Cawdor (1755–1821), who displayed it on a rotating platform so it could be admired from all angles.

Canova’s greatest follower in Britain was John Flaxman (1755-1826), two of whose masterpieces are owned by the National Trust: the monumental early sculpture of the Fury of Athamas at Ickworth, commissioned on the advice of Canova, and the even larger Saint Michael overcoming Satan, the centrepiece of the remarkable collection of modern British sculpture assembled at Petworth by the 3rd Earl of Egremont (1751-1837).

Pre-Raphaelite sculpture

The Pre-Raphaelites are famous above all as painters. However, Thomas Woolner (1825-92), one of the seven original members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, was a sculptor, and sculptor Alexander Munro (1825-71), although not a formal member, was a close friend and associate of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-72) and other followers of the PRB. The National Trust owns perhaps the largest collection of works by Munro, Woolner and other sculptors associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Munro and Woolner’s skills as portraitists can be seen in such works as Munro’s bust of Sir William George Armstrong, 1st Baron Armstrong (1810-1900) at Cragside, or Woolner’s medallion portraits of his friends Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) and Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-92), at Wallington and Carlyle’s House, London, and of Woolner’s wife Gertrude (1845 - 1912) at Wightwick Manor. The Pre-Raphaelite interest in the medieval world, on the other hand, is well exemplified by Munro’s exquisite figure group at Wallington of the doomed lovers Paolo and Francesca, whose tragic story was told by Dante (1265-1321) in his Divine Comedy.

Joseph Edgar Boehm

The Austro-Hungarian sculptor, Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834-1890), was highly regarded in his day but became largely forgotten in the 20th century. Gaining royal patronage as Sculptor in Ordinary to the Queen, and created a baronet in 1889, he was chosen for a number of high profile commissions. Predominantly known for his portrait sculptures, his work can be seen at various National Trust houses. His most celebrated work, his 1874 seated portrait of Thomas Carlyle which established his reputation, can be found at Carlyle’s House in London. An early study for the statue as well as versions in bronze and terracotta are also in the collection. Boehm’s statuette of Carlyle was later cast as a full-size bronze statue and erected on the Chelsea Embankment, not far from Carlyle’s House.

Boehm was also a talented medallist, responsible for designing a medal to commemorate Carlyle’s 80th birthday; Carlyle’s house has a bronze and silver version of the medal, as well as an early sketch in wax (on loan from a private collection). Other important works by Boehm can be seen at Belton House, Buckland Abbey, Fenton House, Hughenden Manor and Waddesdon Manor.

20th-century sculpture

The National Trust has an impressive collection of 20th-century sculpture, including works by prominent artists such as Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), Henry Moore (1898-1986), Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975) and Max Ernst (1891-1976). These works are primarily grouped at three properties: Dudmaston, Willow Road and Shaw’s Corner. Each of these collections was amassed by keen art collectors, and represents a dedicated interest in collecting important 20th-century art.

The architect Ernö Goldfinger (1902-1987), who designed 2 Willow Road as a family home, filled it with furniture and works of art by the most influential figures in the modern art movement, including Henry Moore’s Head, 1938, and Max Ernst’s painted stone, 1934. At Dudmaston, Sir George (1905-99) and Lady Rachel (1908-96) Labouchere installed a bespoke modern art gallery within their 18th-century home to display Henry Moore’s Seated Woman, 1948, Barbara Hepworth’s abstract bronze, Two forms, and an important collection of the work of Anthony Twentyman (1907-1989). Sculptures documenting George Bernard Shaw’s (1856-1950) association with Auguste Rodin can be seen at Shaw’s home, Shaw’s Corner, Hertfordshire. There Rodin’s Head of Honoré de Balzac and a portrait bust of Shaw himself, aged 49, is accompanied by a pair of bronzes of Rodin and Shaw by Shaw’s friend, the Russian sculptor Paolo Troubetzkoy (1866-1938).

Conclusion

The wide range of sculpture across National Trust collections bears witness to its popularity as an art form over centuries. Its variety reflects the collecting habits of generations of individuals and families. Three dimensional, it is a tangible presence, employed in interior and exterior decorative schemes to convey learning, taste and affiliations as well as to commemorate family and friends.

In 2018, with generous support from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and The Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the National Trust embarked upon a research project to catalogue its entire collection of sculpture and to update its online entries. The collection encompasses over 6,000 pieces of sculpture, ancient to contemporary, associated with over 200 historic properties.

At Powis Castle there is an impressive group of Indian sculptures collected by Robert Clive (1725-1774) Commander-in-Chief of British India (1756-60), and his son Edward (1754-1839), 1st Earl Powis and, from 1798 to 1803, Governor of Madras (today’s Chennai). Acquired by the Clives through their East India Company networks, these sculptures are luxury artefacts associated with one of the most important periods in British colonial history.

Hindu, Buddhist and Chinese sculpture can also be seen at Bateman’s, the home of Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), who spent his childhood and early adult life in India and south-east Asia. Among Kipling’s collection is statuette of the Virgin, acquired in Goa, formerly a Portuguese colony.

Asian sculptures

The majority of Asian sculptures in National Trust Collections are comprised of statuettes of Hindu gods and goddesses, Buddhist and Chinese deities, sacred animals as well as Japanese netsuke.