The National Trust looks after one of the most important collections of historic Chinese wallpapers in the world, on permanent display at 18 country houses.

Some wallpapers are decorated with birds and flowers, a symbolic visual language that has a long history in China; others depict bird’s-eye-view landscapes, which express the traditional Chinese ideal of a productive and socially harmonious society. Some of these wallcoverings are actually made up of Chinese prints depicting literary and religious subjects, which no longer survive in China itself.

In addition to their significance within Chinese art history, these wallpapers provide evidence for the longstanding European fascination with Chinese art and design. By examining how Chinese wallpapers were brought to Britain and Ireland, what role they played in interior decoration and how this taste developed, we can better understand the role ‘China’ has been playing in the European imagination over the last four hundred years.

Trade and consumption in the 17th century

In the early 17th century, northwestern European countries like Britain and the Dutch Republic began to trade directly with China. Traders organised themselves in ‘East India Companies’ – joint-stock companies served to spread risk, build up relationships with suppliers and develop markets for new products. Chinese products like porcelain, lacquer and silk were admired for their deep colours, flawless sheen and elegant designs, which as yet could not be achieved by European manufacturers.

Chinese monumental blue and white porcelain jars and a Chinese lacquer screen, late 17th century, at Petworth House

The image of China

Complementing and reinforcing this avid consumption of Chinese goods was a widespread respect for Chinese civilisation. Jesuits missionaries, active in China with the aim of converting the Chinese to Christianity, produced enthusiastic books about the country and its people which found a keen readership back in Europe. The image of China as an ancient, stable, wealthy, rational and virtuous society took hold, contrasting favourably with the religious conflict and near-constant warfare that affected 17th-century Europe.

Luxury goods and the private trade

Accompanying the bulk imports of tea, porcelain and silk, there was a smaller but significant stream of Chinese luxury goods making their way to Europe. Employees of the East India Companies were allowed to trade on their own account to a certain extent, as long as they sold the goods through the Company’s auctions back in London. This was not just an incentive for the traders, but also functioned as a system for the Companies to test new products and develop consumer demand.

It was through this ‘private trade’ that Chinese paintings and prints began to be brought to Britain in the late seventeenth century. From merchants’ advertisements and auction notifications in newspapers we can tell that these pictures were either hung individually, were used to decorate folding screens, fire screens, overdoors and overmantels, or were pasted onto walls as a kind of collage wallpaper.

Paper wallcoverings

The late 17th and early 18th century was also the time when European decorators were developing paper wallcoverings – what we would now call wallpaper – as a cheaper but still smart alternative to tapestries and gilded leather wallhangings. The paintings and prints coming in from China fitted with this wallpaper trend, as well as with the ever-increasing taste for Asian decorative art. Enterprising British paper-makers began to produce wallpapers in pseudo-Asian styles, just as the manufacturers of leather hangings were making their products look like Asian lacquer panels.

At some point, probably in the 1740s, Chinese workshops began producing large woodblock prints in a wallpaper format. It will probably never be known whether it was a European merchant or a Chinese workshop manager who first came up with the idea of this new ‘Chinese wallpaper’ product – it may well have been a fruitful collaboration between the ‘supply’ and the ‘demand’ sides of the East Asian trade. However it may have actually come about, Chinese wallpaper was from the start both Chinese and European, a truly global product.

Woodblock printing

At Felbrigg Hall, Ightham Mote and Uppark examples of early woodblock-printed Chinese wallpaper survive. Until recently it was not realised that these sinuous bird-and-flower panels were printed, but close observation reveals the tell-tale small breaks in the black lines common to woodblock printing.[1] The colours and fine details were subsequently added by hand. The carved wooden blocks must have been very large, as the individual sheets, which were printed from a single block, are over two metres tall. [2]

The wallpaper in the Chinese Bedroom at Felbrigg was hung in 1752 by a London paper-hanger called John Scrutton. It was considered necessary to employ a metropolitan specialist as the individual sheets had to be carefully fitted together to create a convincing panoramic scheme. Chinese wallpaper also tended to be more expensive than British-made paper, so it must have been a painstaking and nerve-wracking job for the paper-hangers. At this stage the different sheets did not overlap or link up visually, so Scrutton cut off the side margins, around the edges of the trees and plants, so that there are no breaks in the scenery and it looks like a continuous garden panorama.

Some of the same panels were used at Ightham Mote, but the visual rhythm is slightly different, presumably because a different paper-hanger was involved here. The reason that the colours are slightly different is that the wallpaper at Ightham was affected by damp and was ‘refreshed’ with unsuitable oil-based paints.

Fragments from yet another woodblock-printed wallpaper have miraculously survived at Uppark. There was a disastrous fire in the house in 1989, and these fragments were found among the debris, having emerged from beneath a later wallpaper. The fragments were carefully conserved along with the other salvageable contents of the house, and in spite of their singed edges the colours are actually remarkably fresh, as they were covered over and thus protected from light for a long time. [3]

Decorative collage

Smaller Chinese prints and paintings were also being used in the 1740s and 1750s to create decorative collages. The paper-hangers again showed considerable artistry in arranging and combining the images. In the Study at Saltram Chinese paintings on paper were combined with prints to create a beautifully symmetrical arrangement.

The original meaning of the pictures was ‘lost in translation’ and they seem to have functioned mainly as evocations of the perceived elegance and sophistication of life in China. Presumably these ‘Indian’ decorative schemes (‘India’ being used as shorthand for ‘Asia’) also projected a sense of cosmopolitanism, especially when combined with imported porcelain and lacquer objects, silk upholstery and curtains, and Chinese-style furniture: the sense that one could enjoy products from the furthest reaches of the globe in one’s own home. In this there is an interesting correlation with the taste for objects and pictures brought back from the Grand Tour, which flourished alongside the fashion for things Chinese.

Painted wallpapers

Research into the dating of these prints and printed wallpapers has indicated that they ceased to be imported after about 1760 and were replaced with fully painted wallpapers. The reason for this may have been the Chinese government’s decision in 1757 to limit and concentrate all the western trade in Guangzhou on the southern coast and prohibit foreigners from visiting other ports. Many of the most sophisticated printing workshops were concentrated in the cities of the Yangzi River delta, further north, and from the late 1750s it may have become uneconomical for westerners to obtain the products from those workshops. Instead, painting workshops in Guangzhou appear to have filled the gap with various types of painted wallpapers.

Some of these new painted wallpapers depicted landscapes, such as one at Blickling Hall, which was probably hung around 1760. Even though it is fully painted, it actually consists of four almost identical landscape sequences, suggesting that the painters were copying sets of master images.

Although these wallpapers can be seen as hand-painted ‘art’, they are simultaneously serially produced decorative products. A number of different painters would have worked on any one wallpaper, each specialising in certain elements, such as architecture, rockwork, foliage or human figures. These wallpapers, and this way of producing them, was part of the Chinese ‘professional’ painting tradition, which specialised in detailed, highly finished paintings for decorative purposes. And while professional painters could be extremely skilled, they did not have the same status and prestige as the ‘scholar amateur’ painters, who tended to work in more monochrome, semi-abstract styles and focus on literary and spiritual themes.

Made for the European market

Certain painting workshops must have specialised in bird-and-flower wallpapers. These now often had brightly coloured backgrounds, something not generally seen in traditional Chinese bird-and-flower paintings and therefore probably a deliberate ‘product innovation’ aimed at keeping the European market interested.

The wallpaper in the State Bedroom at Erddig, probably hung in the 1770s, has a deep green background, but the bird and flower motifs are almost identical to those in the wallpaper at Nostell Priory. The latter was hung by Thomas Chippendale’s firm in 1771 and originally had an off-white background. Other examples of this type survive elsewhere, suggesting that painters must have been producing them in some numbers, based on master models. [4]

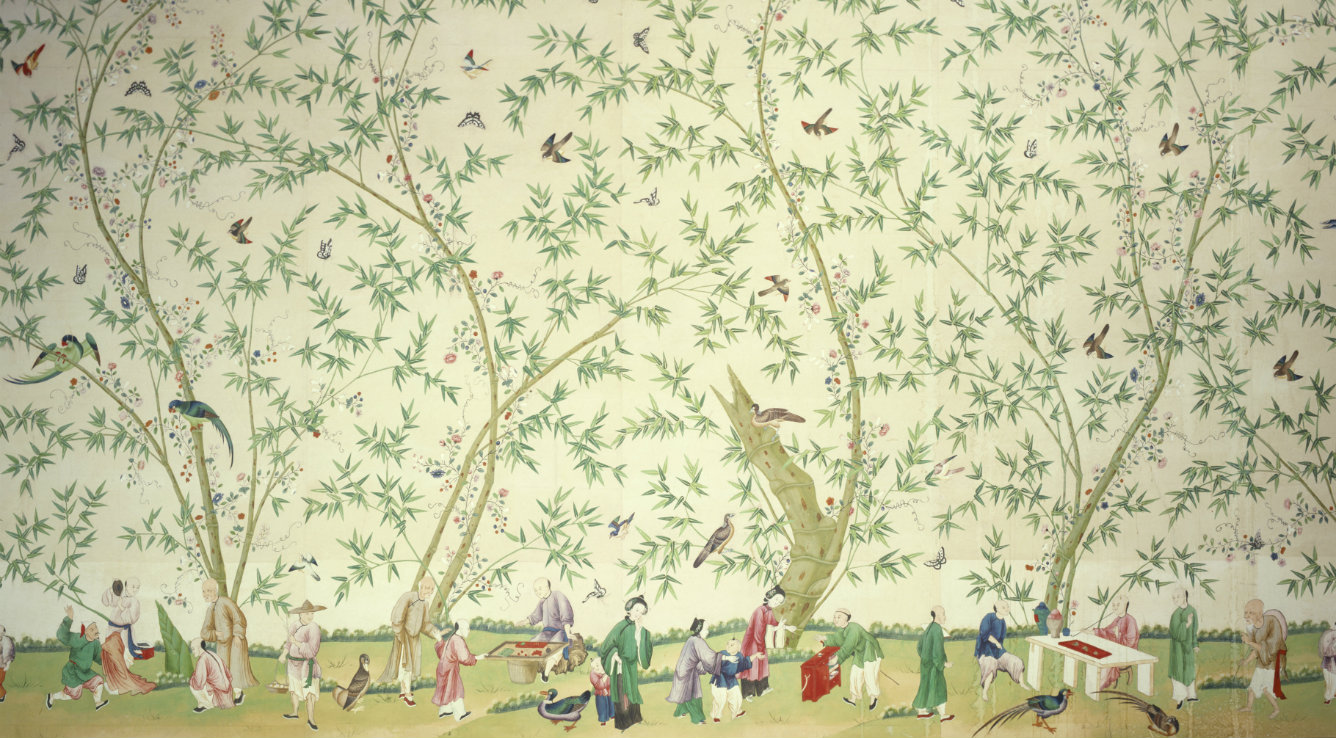

The botanist Joseph Banks praised the Chinese wallpaper painters for what he saw as their scientific accuracy. But the presence of an undoubtedly mythical Chinese phoenix in the wallpaper at Nostell proves that the Chinese artists were treating this scenery not so much as a realistic copy of nature, but rather as an elegant and visually compelling network of auspicious symbols.

Individual birds and flowers had longstanding symbolic connotations (a pair of ducks signifying fidelity, pheasants being symbolic of beauty, peonies indicating ‘rank’ and bamboo ‘humility’) which were reinforced or refined when various motifs were combined. [5]

Continuing innovations

Example of Chinese wallpapers from the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century show how the painting workshops continued to innovate. Balustrades, bird cages and baskets of flowers were added to the bird-and-flower imagery from the late 1780s, to make the scenes look even more like elegant gardens.

The 1790s saw the development of another type of wallpaper that combined human figures, based on genre paintings, along the bottom edge with birds and flowers above. An example of this was hung in the Chinese Bedroom at Belton in about 1840. Although the overall design of the wallpaper is now significantly more stylised than the ‘painterly’ wallpapers from the 1770s, the scenery is executed with great verve and feeling for rhythm.

Although the demand for Chinese wallpaper abated somewhat during the 19th century, it kept being used as part of high-end interior decoration. It was almost as if the taste for Chinese decoration was now so ingrained in Britain that every grand country house was expected to have at least a few ‘Chinese’ rooms. These would generally be relatively informal rooms, like bedrooms, dressing rooms and drawing rooms.

At Penrhyn Castle, two bedrooms and a dressing room were hung with Chinese wallpaper in the early 1830s, contrasting incongruously (but rather wonderfully) with the neo-Norman style of the building. The Chinese wallpaper at Ickworth, probably hung in the mid-19th century, is in what was then the dressing room of Marchioness of Bristol. And when Nostell Priory was being refurbished in the 1870s and 1880s, some new Chinese wallpaper was brought in to decorate a dressing room, complementing the Chinese wallpaper that Chippendale had introduced more than a hundred years before.

Heritage chic

Towards the end of the 19th century, historic Chinese wallpapers began to be bought and sold as antiques. Quite a few of them made their way to the United States, being welcomed not just as exemplars of traditional Chinese art but also as prized specimens of European heritage chic.

Chinese hand-painted wallpaper is still being made today, and significantly its production is masterminded by firms based in Britain and America. A modern-but-traditional Chinese wallpaper was recently installed at Avebury Manor by the British firm of Fromental. Tellingly, it was hung in the dining room, a practice that first seems to have emerged in America in the early twentieth century.

Chinese wallpaper is still a living tradition, a product of an ancient Chinese artistic tradition which was changed, absorbed and preserved by European and American tastes. And it is still very much on display at 18 of the National Trust’s historic houses.

Discover more

Notes

[1] Observed by former National Trust paper conservation adviser Andrew Bush.

[2] One of the as yet unsolved mysteries is whether these was also a Chinese market for these huge prints, or whether they were specifically produced for the European wallpaper market. Whatever the intended market, the subject matter is resolutely Chinese, drawing on the long tradition of bird-and-flower imagery.

[3] A version of the section shown here, with a pair of pheasants, also survives at Schloss Wörlitz, in Sachsen-Anhalt, Germany, testament to the fashionability of Chinese wallpapers across Europe.

[4] The commercial power of this type of wallpaper is proved by the fact that English cotton printers borrowed some of the birds to decorate their products, a few of which survive in the collections of Winterthur (Delaware) and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (New York).

[5] As Jessica Rawson has described, the visual language of birds and flowers functioned (and still functions today) as the Chinese equivalent of the western classical decorative idiom. See Jessica Rawson, ‘Ornament as System: Chinese Bird-and-Flower Design’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 148, no. 1239 (June 2006), pp. 380–9.

Suggested Reading

de Bruijn, E., Bush, A. and Clifford H., Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses, Swindon, National Trust, 2014.

de Bruijn, Emile, Chinese Wallpaper in Britain and Ireland, London, Philip Wilson in collaboration with the National Trust, 2017.

de Bruijn, Emile, ‘Virtual Travel and Virtuous Objects: Chinoiserie and the Country House’, in Jon Stobart (ed.), Travel and the British Country House: Cultures, Critiques and Consumption in the Long Eighteenth Century, Manchester University Press, 2017, pp. 63–85.

Wappenschmidt, Friederike, Chinesische Tapeten für Europa: vom Rollbild zur Bildtapete [Chinese Wallhangings for Europe: from Hanging Scroll to Panoramic Wallpaper], Berlin, Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 1989.

Chinese Wallpaper in Britain and Ireland by Emile de Bruijn was published by Philip Wilson Publishers in 2017.