The history of the English chest of drawers is relatively short; the first examples of cabinet-made pieces were seen in the interiors of the wealthy during the early years of the 17th century. They gradually replaced the simplistic and, in constructional terms, basic chest or ‘coffer’.

As the 17th century progressed, construction techniques developed and improved and by the 1670s the chest of drawers became a staple in middle class dwellings. During this period the majority of case furniture was constructed from British oak or wainscot (a high quality imported European oak). The practice of fully veneering cabinet surfaces became more common place in the 1670s and 1680s but was not fully developed and widely used until the beginning of the 18th century.

At Dyrham Park there is a chest of drawers made in England using British oak, circa 1690. It is stylistically on the cusp of this decorative revolution, representing a group of unexceptional but nonetheless well-made furniture. It is however the interior of this chest that warrants further investigation.

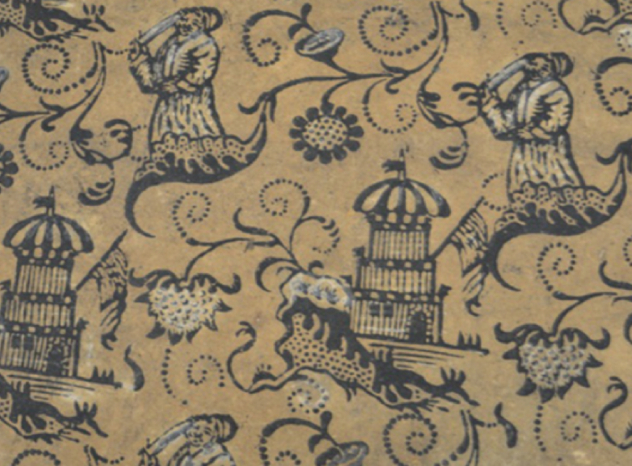

Lining of one of the long drawers of the Dyrham chest

When the drawers are pulled the chest becomes quite extraordinary. All are fully lined with a contemporary polychrome hand printed chinoiserie paper which is in remarkable condition and most unusual. The only other piece of cabinet furniture in a National Trust collection with a late 17th- or early 18th-century paper lining is a chest of drawers at Nunnington, Yorkshire which incorporates three different types of paper.

Plain paper and occasionally marbled paper-lined drawers (or remnants of) are not that uncommon on linen slides, drawer linings and trunk interiors but generally not seen much before 1700. 17th-century trunk makers favoured baize and sometimes silk for the most precious of contents and paper was more commonplace towards the middle years of the 18th century.

Paper linings were often removed from cabinet furniture, presumably as they became tired, torn and dirty, making this discovery all the more exciting as the general condition is superb. The lower drawers are in near unused condition and the colours are vivid and bright.

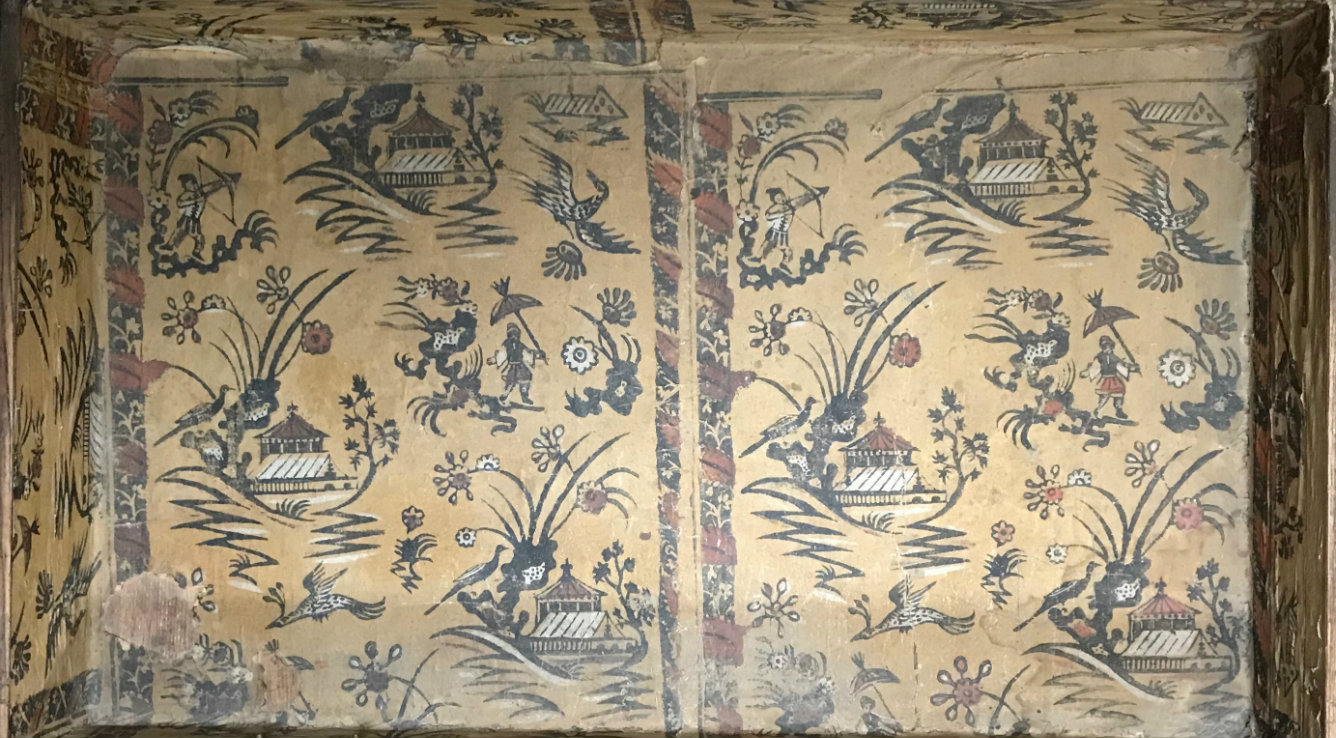

Lining of one of the short drawers of the Dyrham chest

The pattern consists of approximately twelve discrete design elements, some of these being repeated on the same block including a pagoda set within a stylized landscape border and with a bird perched to the left of the building. A figure holding a sun shade and another hunting with bow and arrow. Two other exotic birds in flight and interspersed with flowers and foliage.

The fascination of Japanese and Chinese lacquer-wares influenced both British and European craftsmen and was incorporated and copied onto the surfaces of decorative ornaments and furniture. This ‘chinoiserie’ style became particularly fashionable after the publication of John Stalker and George Parker’s book ‘A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing’ 1688. It is quite possible that this book not only influenced lacquer artists but also perhaps other contemporary designers.

The pattern includes a border on its two ‘vertical’ edges and elements at upper and lower edges that allow a continuous vertical design when two or more sheets are joined together. The paper is hand made with mostly untrimmed deckle edges, block printed and with stencilled colours. Central creases remain from the original fold from the drying process when the sheets were hung over a line. The paper is a ‘medium’ weight and no wire marks (the impression made on the underside of a paper web by the surface contour of the wire mesh it has lain on) or watermarks are apparent.

The order of production is varied; the red and white stencils are printed first onto the yellow ochre ground but not always in the same order on each sheet. The white, which is most probably chalk based, is applied through a stencil and lastly the carbon based black printed for the outlines of the design.

There are a total of eight full sheets used and approximately six cut sheets for the sides of the drawers.

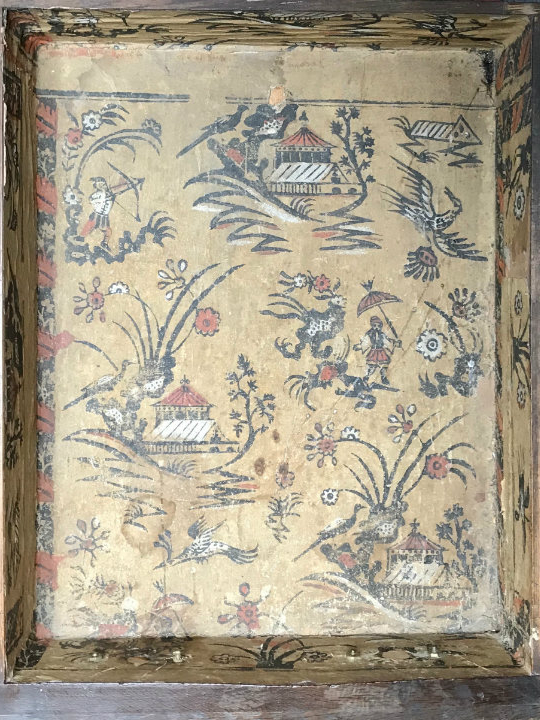

Blew Paper Warehouse trade card, c. 1710

© British Library, BL Harley 5942.40

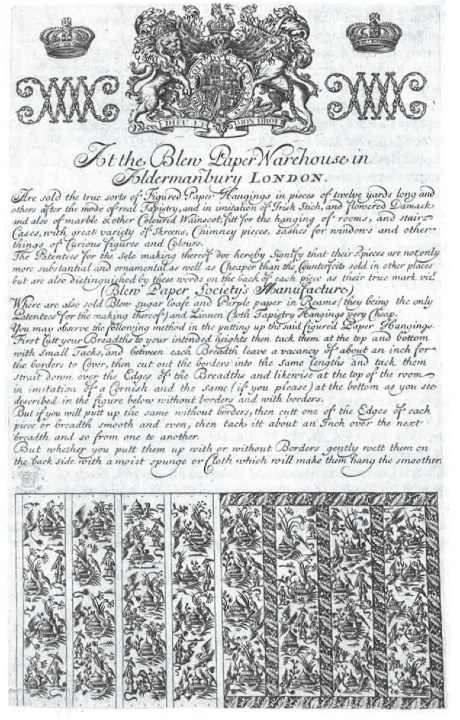

The paper maker is, as yet, uncertain although the late Treve Rosoman (1948-2017), specialist curator at English Heritage and previously of the William Hogarth Trust, attributes similar papers to the somewhat illusive paper-stainer Abraham Price of Blew Paper Warehouse. The National Trust’s paper has a very strong design connection with Blew Paper Warehouse’s trade card, made in around 1710. It is tempting to attribute the Trust’s paper to this London firm, but it should also be remembered that imitations were likely available on the market. As their trade card states, Blew Paper Warehouse papers are better ‘than the counterfeits sold in other places….’ And counterfeits are likely to strongly resemble Blew Paper Warehouse patterns.

Detail of the lining of the Dyrham chest of drawers

Detail of the Blew Paper Warehouse trade card

Two separate papers produced at roughly the same time help to further contextualise the Trust’s paper. The first is the earliest paper in the English Heritage which was discovered in the 1960s in a row of late 17th-century weather-boarded houses in Lambeth. The second is a paper discovered in 2008 in Manor Farm, Ruislip. These two papers have closely related design features, enabling a highly probable attribution (by Treve Rosoman) of these papers to Price. Both these papers appear to have been printed with both a black outline block and a white block and no stencilling. By contrast, the National Trust’s paper was printed with a black outline block and stencilling as described. Although these papers show evidence of differing techniques of production, individual manufacturers of paper hangings did use all of these techniques under the same roof.

Details of the borders: Blew Paper Warehouse trade card (left); the Dyrham paper (middle); the Manor Farm paper (right)

© National Trust/Andrew Bush

It should also be noted that stationers sold ‘…wast (sic) printed paper...’ as described in a trade card for Richard Walkden, Stationer and ‘Trunk makers printed paper’. Printers’ waste was quite often over printed with a simple block printed pattern. Printers also supplied substandard paper or seconds to trunk makers, as can be found in the late 18th-century chest at Dunham Massey.

The re-discovery of this stunning decorative paper, in such good condition and unusually still in its original location in its chest, is a rare addition to the relatively few surviving papers of this period. It significantly increases the number of papers that can possibly be attributed to The Blew Paper Warehouse, one of the earliest manufacturers of wallpaper. Design links to this maker and to the relatively recently discovered Manor Farm paper, give hope that future discoveries might help to further increase knowledge on this special National Trust paper.

In 2015, with generous support from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and the Royal Oak Foundation, the Trust embarked upon a research project that seeks to catalogue the entire furniture collection and update its online entries.

Photographic credit

All photos, unless otherwise stated, are © National Trust/James Weedon.