100 Years of Ulysses by James Joyce

2 February 2022 marks the centenary of the publication of James Joyce’s modernist masterpiece, Ulysses.

From its early days as a work in progress, to its eventual British publication after years of being censored, the production and reception of this groundbreaking novel is interwoven with National Trust places and book collections.

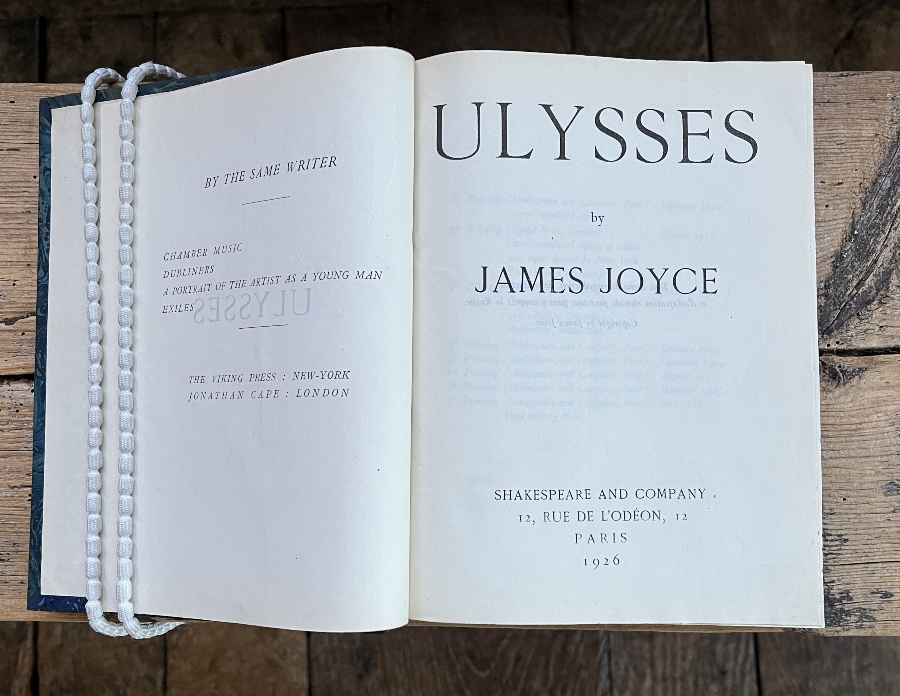

There can be few more iconic books than Ulysses, a novel that has had a profound effect on the development of fiction and the inventive use of the English language. Famously utilising a stream of consciousness method, and packed full of enigmatic words and phrases, Ulysses charts the course of a single day – 16 June 1904 – in Dublin. The book and its author, James Joyce (1882-1941), have been the focus of much interest and study over the decades and, despite it being a notoriously difficult novel to read, the story of its publication is well known to many. First published by Sylvia Beach from her famous Parisian bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, the novel fell foul of obscenity laws in Britain and the United States, leading to a ban on its publication for over a decade.

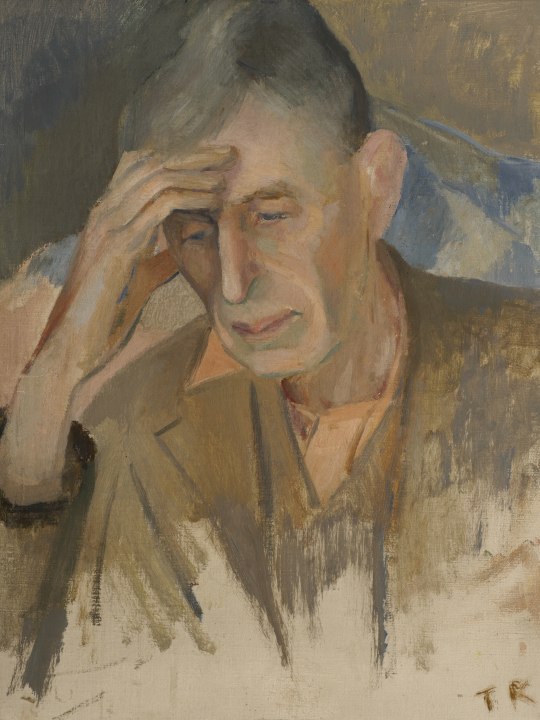

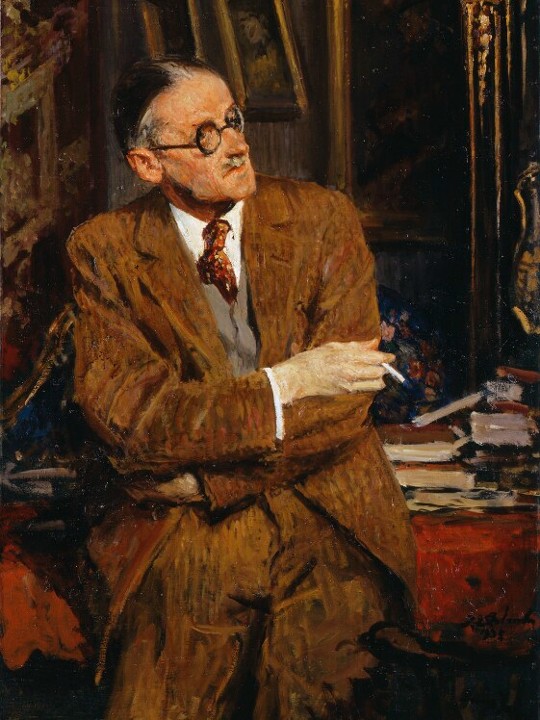

James Joyce (1882–1941) by Jacques-Emile Blanche, 1935

NPG 3883 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Early owners

This notoriety has led to Ulysses being one the most recognisable of novels – the first edition’s blue paper covers with simple white lettering are among the most famous in the history of book design. Unfortunately, there are no longer copies of the first edition in the Trust’s book collections; George Bernard Shaw famously refused to be a subscriber, declaring that no 'Irishman, much less an elderly one, would pay 150 francs for a book.' [1] However, we know that T.E. Lawrence was an early subscriber of the novel, and that his copy formed part of the collection of books at Clouds Hill. Winston Churchill is listed as an owner of a deluxe edition of Ulysses, which may have at some time been part of the library at Chartwell.

Virginia and Leonard Woolf also owned an early edition of the novel. On 14 April 1922, Virginia wrote to her brother-in-law, Clive Bell, to say that they had spent £4 on a copy of Ulysses: ‘I have him on the table. His pages are cut. Leonard is already 30 pages deep. I look, and sip, and shudder.’ [2] It may be that some of the Woolfs’ reading of the book took place at Monk's House, their country retreat in East Sussex.

Ulysses and the Hogarth Press

The Woolfs’ connection with Joyce’s masterpiece predated its 1922 publication by some four years. On 14 April 1918 they were visited at their Richmond home by Harriet Shaw Weaver, editor of The Egoist journal, a literary patron and a great supporter of Joyce. Weaver brought with her the incomplete manuscript of Ulysses in a brown paper bag, with the hope of persuading the Woolfs to print and publish it via their fledgling Hogarth Press imprint. Leonard recognised the import of the work, describing it as a ‘remarkable piece of dynamite’ but, like many of the other printers to whom the novel had been offered, he and Virginia feared being prosecuted for, what was considered at the time, the book’s obscene content. [3]

There were also practical matters to consider. In those early days of the Hogarth Press, the only printing equipment the Woolfs had was a small, hand-operated press that they had acquired in March 1917 and which was installed in their dining room. By their estimation, the printing of Joyce’s epic novel would take at least two years, a period that was unthinkably long for the printers and the author.

Within a couple of years the Woolfs had expanded their printing operation and acquired a treadle-operated Minerva printing press. One such printing press is thought to have been given to Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson as a housewarming present by the Woolfs, and is now installed in the top of the Tower at Sissinghurst. A much quicker machine to operate and print on, it is tempting to speculate as to whether or not the Woolfs might have taken the Ulysses commission had they owned such a press at the time of Harriet Weaver’s visit.

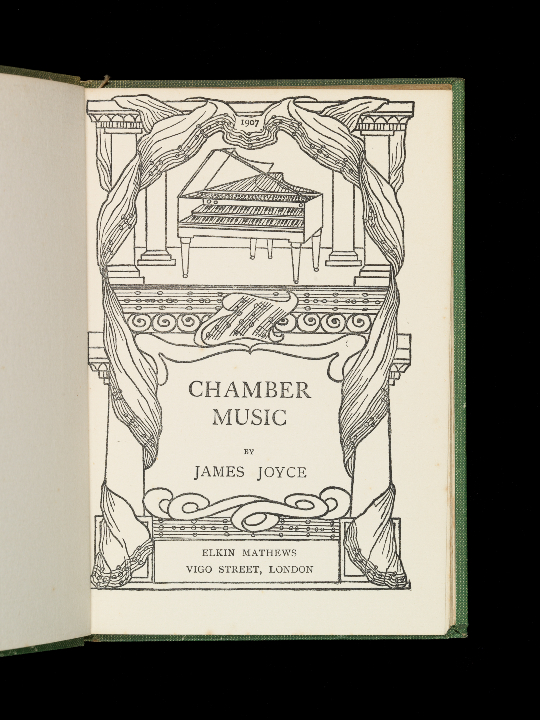

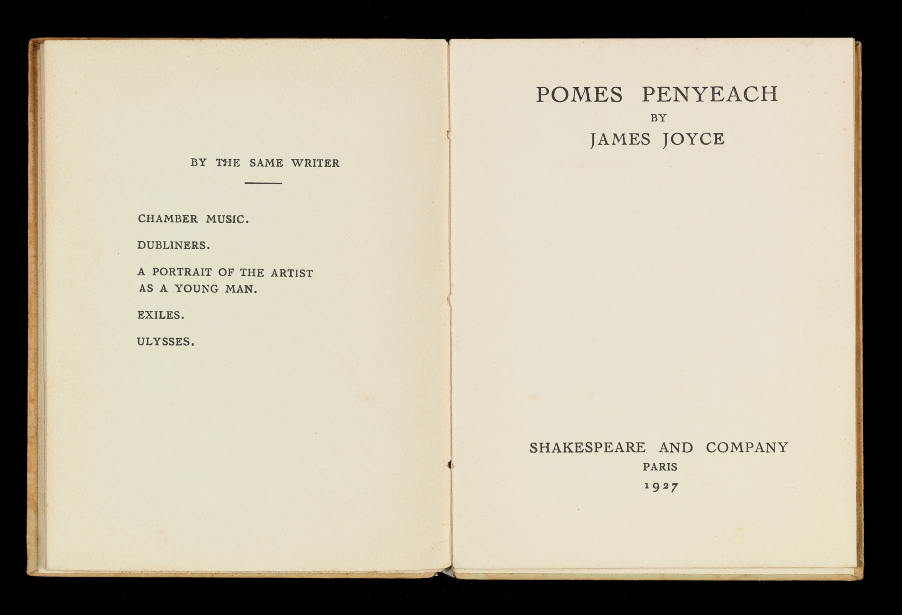

Over the years, Virginia had much to say about her fellow modernist, Joyce, and Ulysses. Although she admired Joyce’s short stories in Dubliners, and acknowledged that his method of writing was ‘highly developed’, she struggled with Ulysses, declaring that ‘never did any book so bore me’ and describing it as trash. [4] It was a sentiment echoed by Vita Sackville-West who, unlike her husband, hated the novel. Vita does, however, appear to have taken an interest in Joyce’s poetry; within her collection at Sissinghurst is a first edition of Chamber Music (Joyce’s first book, published in 1907) and his Pomes Penyeach, published by Shakespeare and Company in 1927.

Harold Nicolson meets James Joyce

At around the time of the gifting of the ‘Hogarth Press’, Harold Nicolson had his first encounter with James Joyce. In July 1931, they attended a lunch at the London home of the American writer, Gladys Huntington, and her husband, Constant, the head of the London office of the publisher, G.P. Putnam's Sons. In the course of their conversations Nicolson discussed his plans to give a talk on the BBC about Joyce and Ulysses. Excited to hear about his proposed airtime, Joyce offered to send Nicolson some books that might be useful in preparing his talk.

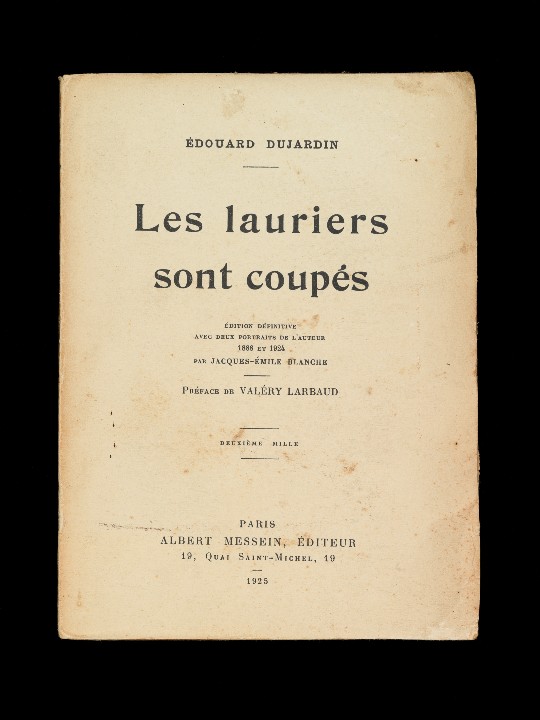

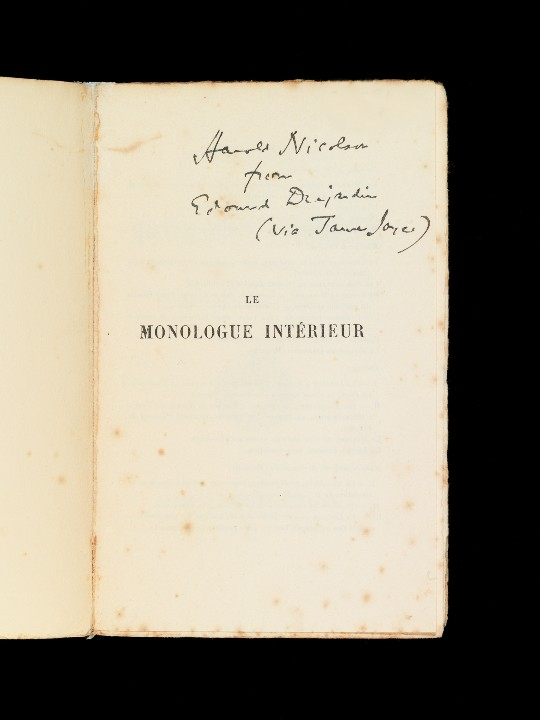

These books, with inscriptions by Harold recording their Joycean provenance, are still in the collection at Sissinghurst. They are both by Édouard Dujardin, the French writer whose stream of consciousness style (or, as Dujardin coined it, 'le monologue intérieur') in his novel, Les lauriers sont coupés, had a great influence on Joyce and Ulysses. Harold’s numerous notes in the backs of the books, including his definition of the interior monologue – ‘a speech without an audience’ – show how useful they were in informing his BBC lecture.

Joyce organised something of a listening party for the radio programme, only to hear Nicolson apologise for not being able to deliver the talk owing to pressure from the BBC, especially in regard to his plans to mention Ulysses by name. Two weeks later a compromise was reached and Nicolson was able to deliver his lecture, ‘The Significance of James Joyce’, some of the content of which was derived directly from the books sent to him by Joyce.

In February 1934 Harold Nicolson had a second encounter with James Joyce. Having obtained Joyce’s Paris address directly from Sylvia Beach at Shakespeare and Company, Nicolson was greeted at the apartment door by Joyce’s son, Giorgio, before Joyce himself joined Nicolson in the apartment’s drawing room. Harold’s recollection of their meeting is described brilliantly in his 1943 book, The Desire to Please:

Suddenly, and very quietly the door opened and Joyce crept into the room. He turned his sensitive face towards the windows, moving it rapidly from side to side, seeking for the bunched shadow somewhere which would represent his guest. It was obvious that he had just shaved himself, and as he advanced cautiously, feeling the furniture gingerly, with fingers outstretched below the level of his waist, he dabbed with his left hand and a large silk handkerchief at his cheek and chin. He was very neatly dressed; upon his fingers were several heavy encrusted rings; his sockless feet slipped tentatively along the parquet in carpet slippers of blue and white check. He found a chair beside me … From time to time his hand would finger and adjust the loose lenses in his heavy steel spectacles. His half-blindness was so oppressive that one had the impression of speaking to someone who was very ill indeed. [5]

At this meeting Joyce attempted to persuade Nicolson to work with him on overturning the ban on the UK publication of Ulysses. Joyce's plan was to send Nicolson a copy of the first edition of Ulysses, which would inevitably be seized by the authorities. After which Nicolson would initiate legal proceedings against the government for confiscating his property, which would in turn attract much publicity and force the government to overturn the ban. In the course of their conversation, Joyce was keen to impress on Nicolson that even the Pope had blessed Ulysses - a sure sign that the time was right for the book to be published. [6]

'Incredible virtuosity'

Although Joyce’s plan didn’t come to fruition, two and a half years later the first British edition of Ulysses appeared, published by Bodley Head on 3 October 1936. Although the publisher was cautious about the issuing of the novel, and some booksellers refused to stock the book, no prosecution was forthcoming, allowing reviews to appear in the press. One of the earliest reviewers of Ulysses was the artist and critic, Alan Clutton-Brock, whose 1926 copy of Ulysses – the 8th Shakespeare and Company printing and the first with wholesale corrections of Joyce’s text – is in the collection at Chastleton House, the home he inherited in 1955.

Clutton-Brock’s decidedly positive review of Ulysses appeared in the Times Literary Supplement on 23 January 1937. He saw in Joyce’s work an exuberant inventiveness with the English language, akin to Shakespeare and other writers of the Elizabethan age. In the TLS review he writes that the lack of linguistic rules in Ulysses 'only enables Mr. Joyce to exercise all his talent, his almost incredible virtuosity, to the full … it is above all the profusion and fertility of language that will fascinate the reader.' [7]

In finding much merit in Joyce’s work, Clutton-Brock was following in the footsteps of his father, Arthur, who corresponded with Joyce and also reviewed his writing for the TLS (his critique of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man appeared in the 1 March 1917 issue). Joyce respected him as a critic, writing that Arthur ‘has always treated my writings generously and with understanding.’ [8] It is a degree of understanding that was passed on to the junior Clutton-Brock.

Legacy

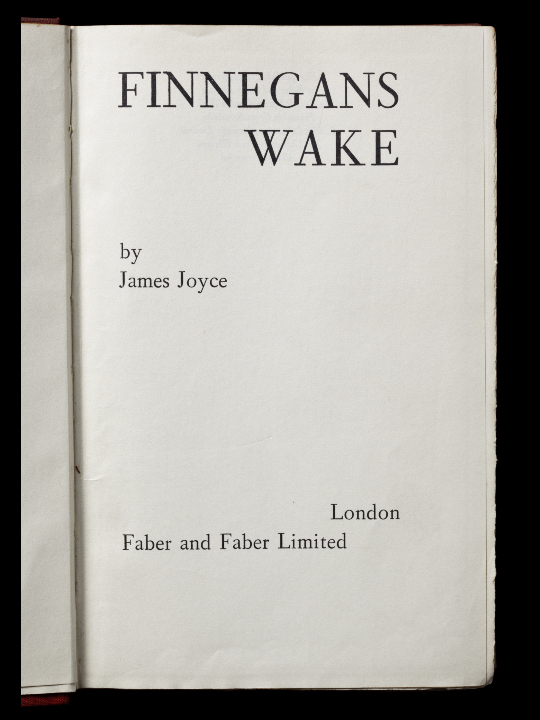

After Ulysses, James Joyce produced one more novel - Finnegans Wake - before his death in 1941. Even his staunchest admirers found his final novel difficult to comprehend; Harold Nicolson, who reviewed it for the Daily Telegraph, declared it to be a 'selfish' novel, one in which the author had entirely abandoned his reader. [9]

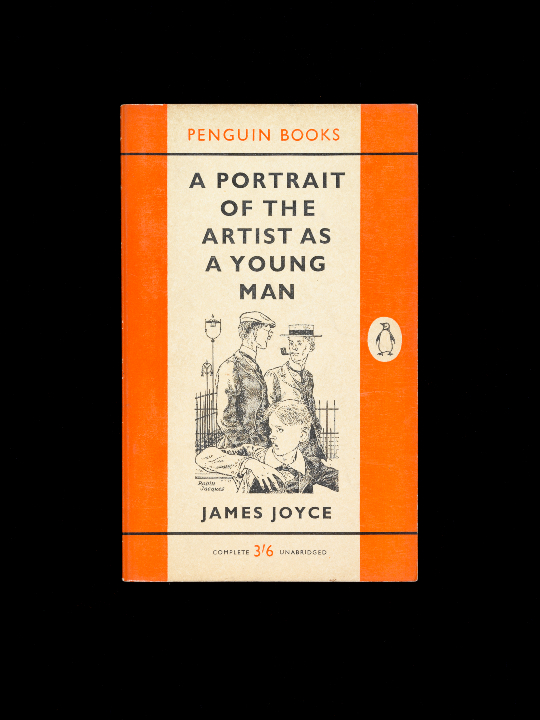

Yet, despite the perceived difficulties in approaching his writings, Joyce's legacy and influence has endured. Generations of readers have continued to find plenty to enjoy in his writing and challenges to relish. A testament to his appeal and importance can be seen in the number of copies of his work in National Trust libraries - from a contemporary copy of Dubliners (1926) at Plas yn Rhiw, to Penguin paperback editions of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1960) at Scotney Castle and Ulysses (2000) at 575 Wandsworth Road.

Notes

[1] Letter from George Bernard Shaw responding to James Joyce's Ulysses, 1921, Harriet Shaw Weaver Papers: Correspondence, literary and business papers. Vol. II (ff. 219). 1920-1922, British Library, Add MS 57346.

[2] Virginia Woolf and Joanne Banks, Congenial Spirits: the Selected Letters of Virginia Woolf, London 1989, p.141.

[3] Victoria Glendinning, Leonard Woolf: a life, London 2006, p. 221.

[4] V. Woolf, Congenial Spirits, pp. 99, 183.

[5] R.B. Kershner, ‘Harold Nicolson’s Visit with Joyce’, James Joyce Quarterly, vol 39, no. 2, 2002, pp. 327-8.

[7] Alan Clutton-Brock, ‘Interpretations of Ulysses’, The Times Literary Supplement, issue 1825, 23 January 1937.

[8] Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the making of 'Ulysses', London, 1972, p. 76.

[9] Gordon Bowker, James Joyce: a Biography, London 2012, p.509.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank David Brunetti Photography and the staff at Chastleton House, Scotney Castle and Sissinghurst Castle Garden, especially Barbara Banning, Helen Davis and Eleanor Black, for their work in photographing items from the National Trust's collections.