Catherine Lucas, Lady Pye (1617–1701/2), 'Dame Catherine Pye'

Henry Giles

Category

Art / Oil paintings

Date

1639 (signed and dated)

Materials

Oil on canvas

Measurements

1030 x 1020 mm

Place of origin

England

Order this imageCollection

Bradenham, Buckinghamshire

NT 765487

Summary

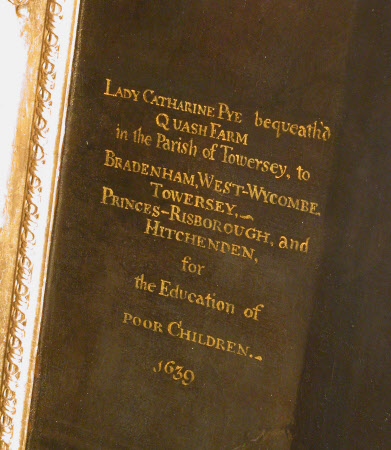

Oil painting on canvas, Catherine Lucas, Lady Pye (1617–1701/2), 'Dame Catherine Pye' by Henry Giles, signed and dated: mid-left: Anno Domini. 1639 Aprili / Henry Giles f [ecit]. Inscribed, top left: LADY CATHERINE PYE bequeath’d / QUASH FARM / in the Parish of Towersey, to / BRADENHAM, WEST-WYCOMBE / TOWERSEY ~ / PRINCES-RISBOROUGH, and / HITCHENDEN, / for / the Education of / POOR CHILDREN ~ / 1639. A three-quarter-length portrait of a young woman, turned slightly to the left, gazing at the spectator, wearing a black dress with white lace at neck and cuffs, in large black hat. Left hand raised to her waist, right hand by her side. The sitter is shown three-quarter-length, standing, turned to left, looking out, her right arm by her side, her left hand (with wedding ring, and with small pearl-cum-jewel bracelet on her wrist – as on her right wrist). She wears the typical costume of a London Citizen’s wife, a black dress, slit in the front to reveal a [--------?--------] beneath, with three layers of plain white muslin collars, to the top of her neck and meeting at a black bow in front, plain muslin cuffs, lace cap, and wide-brimmed black hat. A curtain behind her to the right, a table covered by a [?olive green] cloth to the left, with on it a finely-bound blue book, with its pink ribbons untied.

Full description

The fourth of five daughters – the youngest of whom, Margaret, became the celebrated authoress-Duchess of Newcastle – and three sons – Sir Thomas; John, Lord Lucas of Shenfield; and the Royalist ‘martyr’, Sir Charles – of Sir Thomas Lucas (d.1625) of St. John’s, Colchester, and Elizabeth, daughter of John Leighton, of London. Their father having died young, the daughters, in particular, received an exceptional education at the hands of their mother, as described in the True Relation of the Birth, Breeding, and Life of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, written by Herself, originally published in Nature’s Pictures drawn by Fancy’s Pencil to the Life, London, 1656; reprint ed. Sir Egerton Brydges, MP, Lee Priory, 1814, pp.3-6. According to this, they were bred “in plenty, or rather with superfluity”, and trained “virtuously, modestly, civilly, honourably, and on honest principles.” Their dress was “neat and cleanly, fine and gay”, but also “rich and costly”. “Likewise we were bred tenderly ... instead of threats, reason was used to persuade us.” Their mother considered it her duty to maintain her family “to the height of her estate, but not beyond it”, thus giving her children “breeding, honest pleasures, and harmless delights, out of an opinion that if she bred us with needy necessity, it might chance to create in us sharking qualities, mean thoughts, and base actions.” She hence gave her daughters tutors “for all sorts of virtues, as singing, dancing, playing on musick, reading, writing, working, and the like”, as well as for foreign tongues. Margaret herself was a beauty, but she described her brothers and sisters as “every ways proportionable; likewise well featured, clear complexions, brown haires, but some lighter than others, sound teeth, sweet breaths, plain speeches, tuneable voices, I mean not so much to sing as in speaking, as not stuttering, not wharling in the throat, or speaking through the nose or hoarseley, unless they had a cold, or squeakingly” (op. cit., p.15). Margaret, much the youngest, had what she herself described as a “supernatural affection” for Catherine (op. cit., p.12), the sister nearest to her in age, continually plaguing her, as she herself later admitted in a letter written to her from exile in Holland, out of fear that she might die or be dead, when eating, praying, or sleeping; and before her marriage, lived with her in London. With all these qualities, it is unsurprising that Catherine made (in terms of wealth) a good match, in 1635, with the future Sir Edmund Pye, Bt (c.1607-1673; cr. 1641), of Leckhampstead and (later) Bradenham, the latter of which he bought in or just after 1642, and where he was to build the Manor in the Artisan Mannerist style, around 1670 (their arms feature on the staircase ceiling). He does not appear to have been in any way related to the celebrated Sir Walter Pye, of The Mynde, Hertfordshire, or to his nephew, the Parliamentarian Sir Robert Pye, of Faringdon, Berkshire, but was the grandson of a butcher, and the son of Edmund Pye of St Martin’s Ludgate and Leckhampstead, a rich scrivener, and of Martha Allen, sister of Alderman Allen, Haberdasher (hence Catherine’s city wife’s dress). Thanks to his marriage into Royalist circles, he “voluntarily forsook his dwelling in the Parliament’s quarters” (i.e. Bradenham) on the outbreak of the Civil War, and joined the King at Oxford. He was fined £3,065 by Parliament for his delinquency, which he had not paid in full by 1654. Nonetheless, no Royalist activity was ascribed to him during the Interregnum. After the Restoration, he was elected MP for Chipping [now High] Wycombe, in 1661, and was a moderately active member of the Cavalier Parliament, remaining a member until his death. He and Catherine had two daughters, Elizabeth (1639/40-1713), the younger, who married the Hon. Charles West (1644/5-1684), and Martha (d.1693), the elder, who in 1662 married John Lovelace (c.1640-1693), of Hurley, who was to succeed his father as 3rd Baron Lovelace in 1670. She was disinherited by her father’s will, dated 26 July 1693, and died on 27 September that year, but, her sister having died without issue, her daughter Martha (c.1665-1745) was declared in 1701 to be entitled to the barony of Wentworth (which, after her death without issue, went to her Noel cousins). The stipulation in Dame Catherine’s indenture conveying the farm (known as Quash farm) at Towersey to certain trustees, dated sometime after her death, 15 Nov. 1713, was that the income should be used to provide instruction for twenty boys or girls annually. They were: “to be taught to know the letters of the Alphabeth, and to spell English truely, and to get perfectly by heart the Church of England Catechism, and no other.” A writing master was to teach ten of the boys “to write one hand very well”, and to cast accounts – any surplus, to go towards apprenticing them (cf. George Lipscomb, The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham [1847], vol. I, p.461) [wrongly giving the year as 1733 – corrected in vol. III, p.558, which also says: “It is stated that no School-house has been built”.] Thomas Langley, in The History and Antiquities of the Hundred of Derborough, and Deanery of Wycombe, Buckinghamshire (1797; p.181), says that the improved value of the estate meant that in Bradenham alone, twelve children benefited from it: was there a school-house there, which housed the picture?

Provenance

Presumably commissioned by the sitter or her husband, and presented after her death (1713) to one of the communities named in the inscription; acquired by a Dashwood trustee of her bequest?; thence by descent to the 10th and 11th Baronets, and to Sir Edward Dashwood, 12th Bt, West Wycombe; by whom sold to the National Trust for Bradenham Manor in 2000/2001; on loan to the Buckinghamshire County Museum in Aylesbury

Marks and inscriptions

'Lady Catharine Pye bequeath'd/ Quash Farm/ in the Parish of Towersey, to/ Bradenham, West-Wycombe,/ Towersey,/ Princes-Risborough, and/ Hitchenden,/ for/ the Education of/ Poor Children./ 1639'

Makers and roles

Henry Giles, artist