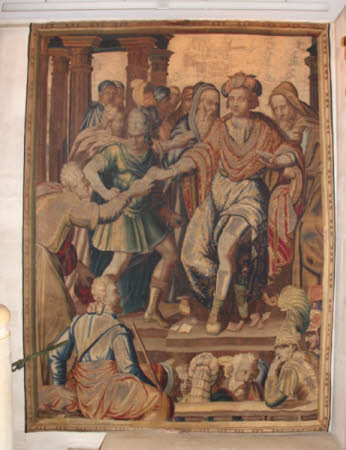

The Requests of the People

Faubourg Saint-Marcel Workshop, Paris

Category

Tapestries

Date

circa 1610 - circa 1620

Materials

Tapestry, wool, silk and metal thread, 7 warps per cm

Measurements

3.03 m (H); 2.56 m (W)

Place of origin

Paris

Order this imageCollection

Anglesey Abbey, Cambridgeshire

NT 516752

Summary

Tapestry, wool, silk and metal thread, 7 warps per cm, The Requests of the People, Faubourg Saint-Marcel Manufactory, Paris, c. 1610-1620. A man wearing a cloth hat and blue and red robes sits on a large chair to the right, reaching out with one hand to receive a small scroll of paper from a man who ascends steps to meet him from the lower left. More scrolls of paper lie on the ground around the seated man's feet. Behind the two figures a soldier stands in front of a crowd of men in togas by a columned structure. At the lower edge of the scene there is a stone ledge with a man seated on it on the left and a soldier leaning on it on the right, and a row of heads visible on the other side of it. The tapestry has a narrow border with a bead-and-reel pattern around all four edges. A blue galloon running outside the side borders has been folded in. At the top and bottom there would have been wide borders, but these have been folded in, as have parts of the main field inside the upper and lower borders.

Full description

The tapestry is part of a large series of 'Stories of Queen Artemisia' that was woven in the Parisian workshops of the Faubourg Saint-Marcel in the early seventeenth century. The designs for the 'Artemisia' series have their origin in the 1560s. Nicolas Houel, an apothecary at the French Court and also an amateur poet, devised an epic on the life of the ancient Queen Artemisia as a gift for Catherine de'Medici who, following the death of her husband Henri II in 1559, now ruled France as Regent in the place of her 11-year-old son. Houel's epic, written in c. 1561-2 and entitled ‘Histoire de la Royne Arthemise’ (Story of Queen Artemesia) framed the life of the ancient queen, who also ruled as a regent in the place of her son, in a series of episodes the consciously echoed Catherine's own life. The story served as an allegorical compliment to Catherine, emphasising the divine love between her and Henri II, the fitting manner in which she had mourned him, her wise handling of diplomatic and political events, and, especially, the prudent way in which she supervised the education of her son, the future king (Adelson 1994, pp. 164-8). While writing his initial prose work Houel began composing sonnets on various episodes of the Artemisia story and commissioned accompanying illustrations, which he suggested could form the basis for a series of tapestry designs. Many of the drawings include decorative surrounds suitable for tapestry borders. ‘The Requests of the People’ appears as drawing no. 39 in the original illustrated album, and the subject is based on a passage in Chapter 1 of the second book of Houel’s prose work. The tapestry shows a judge surrounded by councillors and soldiers, receiving the grievances of the people and meting out justice. The figures at the bottom, whose heads alone are visible, represent the populace. Houel’s text reads: “… having announced the convocation and assembly of states of her entire kingdom, this prudent princess [Artemisia] charged the judges of the provinces to patiently receive the grievances of the people, right down to the lowliest subjects” (quoted in Fénaille 1903-23, vol. 1, p. 164). No tapestries of the ‘Story of Artemisia’ were woven for Catherine de'Medici. When Henri IV decided to establish two new Royal tapestry manufactories at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the designs were woven at the low-warp workshop at the Faubourg Saint-Marcel manufactory. The first set of ‘Artemisia’ tapestries was made for Henri IV himself. Many more sets were woven in the early seventeenth century for French and European patrons, and a number of new designs were added to Houel's original scenes. The continued popularity of the series in early seventeenth-century France has been attributed to the fact that after Henri IV’s assassination in 1610 the country was once again ruled by a regent, Marie de’Medici, until her son Louis XIII assumed power in 1617. More than one designer was involved in creating the drawings for Houel's original album, and the degree of involvement of different artists has been the subject of much debate. The majority of the fifty-three surviving drawings are attributed to Antoine Caron (1521-1599), but some may be by other artists (Ehrmann 1964; Ehrmann 1986; Auclair 2000). Further designs were added in the early seventeenth century, some of them by the artists Henri Larembert (c. 1540/50 – 1608) and Laurent Guyot (1675/80 – after 1644), both of whom may also have been involved in making the cartoons for the series. 'The Requests of the People' is a reduced version of one of the early drawings found in Houel's albums. The original drawing is in the Cabinet des Estampes at the Musée du Louvre (illustrated in Fénaille 1903, vol. 1, p. 164). It includes additional figures at either side, and the scene takes place beneath a columned structure, only part of which is visible in the tapestry at Anglesey Abbey. The drawing is closely followed in other surviving weavings of the scene, for example one formerly in the Munich Residence (Göbel 1933, p. 171). The Anglesey Abbey tapestry represents only the central section of the design, and it was originally part of asset that included two further narrow panels with the figures from the two sides of the design, woven as separate hangings with their own borders. These side pieces now belong to the Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum of Art, San Diego (see below). The division of a single design into three pieces suggests that these panels were woven to fill narrow spaces of wall, probably as entrefenêtres (designed to hang between windows). There are also some minor alterations to the design when compared to the drawing and the Munich weaving, most notably the head of the central figure. In the drawing he turns to the left to look at the man presenting a petition to him, whereas in the Anglesey Abbey tapestry he looks out at the viewer, and wears a different style of headdress. The head at Anglesey Abbey in fact directly copies the head of Coriolanus in ‘Coriolanus Receives a Delegation from Rome’ from the ‘Story of Coriolanus’, also woven at the Faubourg Saint-Marcel manufactory in the early seventeenth century (Denis 2011, fig. 20). Parts of the tapestry at Anglesey Abbey are currently hidden, with 6-8 inches of the main field folded in at the top and bottom, as well as most of the upper and lower borders which are over a foot wide each. This seems to have been done in order to fit the tapestry into the low section of wall on the staircase where it now hangs. The tapestry was woven without side borders but has plain blue galloons outside the narrow bead-and-reel decoration, also now hidden. A photograph and description of the tapestry in 1922 (see below) reveal that the upper border included a coat of arms, and the lower border had a central cartouche with the initials ‘AM’ over crossed sceptres, with a design of rinceaux to either side. The same ‘AM’ monogram appears on a number of other ‘Artemisia’ tapestries, but its exact meaning is unclear: it has been suggested, variously, that it may refer to Marie de’Medici, to Anne of Austria, or even to the two queens jointly (‘Anne’ and ‘Marie’) (Adelson 1994, p. 170). On the right-hand galloon of the tapestry, now hidden, are two signatures: one comprising the initials ‘FM’, and another in the form of a flower. The ‘FM’ mark was long assumed to be that of Philippe (or Filippe) de Maecht, one of the Flemish weavers who arrived in Paris when the Faubourg Saint-Marcel manufactory was established in 1603. De Maecht worked at the Faubourg Saint-Marcel manufactory until about 1619, when he travelled to England to become head weaver at the newly established Mortlake manufactory. However as Adelson points out, de Maecht signed his name with the initials PDM entwined horizontally, and not with the letters FM. Adelson also notes that while he was still working in Paris de Maecht’s PDM monogram often appeared in tandem with the FM monogram, and argues, quite logically, that the two marks must therefore belong to two different weavers – something first realised by Volk-Knüttel (Volk-Knüttel 1976, p. 136; Adelson 1994, p. 180). Adelson also notes that the FM mark frequently appears in conjunction with other marks – including the flower that also appears on the Angelesey Abbey tapestry – and argues that it may be a general mark of the Faubourg Saint-Marcel manufactory (Adelson 1994, p. 181). The flower mark has also eluded identification, although it must be the signature of the head of one of the workshops at the Faubourg Saint-Marcel that wove tapestries with gold thread (a privilege reserved only for specific workshops due to the value of the materials involved) (Adelson 1994, p. 183). The flower mark appears along with the ‘FM’ monogram on a number of the other surviving ‘Artemisia’ tapestries, including part of a set made for a member of the Barberini family and now in the Minneapolis Institute of Art. ‘The Requests of the People’ can be linked on the basis of its heraldic borders (described in a 1922 sale catalogue), and the two related side panels mentioned above, to a set of eighteen ‘Artemisia’ tapestries woven for Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy in c. 1620. This set appeared in the posthumous inventory of Christine of France (who had married Charles Emmanuel’s son and successor as Duke of Savoy, Victor Amadeus I) in 1664. Ten pieces remain in the ex-Savoy collections: six tapestries in the Palazzo Chiablese, Turin, two (one of them a fragment from a piece in the Palazzo Chiablese) in the Museo Civico, Turin, and one on the Palazzo Reale, Turin. Others have left the Savoy collections: four belong to the Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum of Art, San Diego, California; one is in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, and one is on deposit from the Church of Saint-Georges-sur-Cher at the Château de Blois. Others are in private collections or untraced (Denis 1992, p. 30; Adelson 1994, fn 120, pp. 198-99). The Anglesey Abbey piece has until now been classed as one of two ‘lost’ pieces from the Savoy set. It was last recorded in the Camilla Lacey Sale, 28 November 1922 (reference provided in Adelson 1994, fn 120, p. 199). The illustration in the sale catalogue shows the two signatures in the right hand galloon and the crossed-sceptre device with the initials ‘AM’ in the lower border. The upper border is not visible but the catalogue entry mentions that it contains a coat of arms. It is not known whether Lord Fairhaven bought the tapestry directly from the Camilla Lacey Sale, or whether he acquired later through a intermediary. What is clear is that the identity of the tapestry had been lost. In the Camilla Lacey Sale catalogue it was described as “An early panel of Gobelins tapestry”, with a note, “said to have been a gift from Marie de’Medici’, but the subject was unknown. The folding in of the borders made the origin of the tapestry harder to discern, and latterly it has been described in National Trust inventories as a Flemish tapestry, the subject Pontias Pilate. (Helen Wyld, 2013)

Provenance

Made for Charles Emmanuel, Duke of Savoy (1562-1630) and purchased in 1620 or soon after; posthumous inventory of Christine of France (1606-1663); Henry Anthony Van Hievelt, Camilla Lacey sale, 28 November 1922, lot 120; acquired (at this sale or later) by Huttleston Rogers Broughton, 1st Lord Fairhaven (1896-1966) for Anglesey Abbey; bequeathed by Lord Fairhaven to the National Trust with the house and the rest of the contents.

Credit line

Anglesey Abbey, The Fairhaven Collection (The National Trust)

Marks and inscriptions

Bottom of right hand galloon (now hidden): 'FM' monogram Bottom of right hand galloon (now hidden): weaver's mark in the form of a flower

Makers and roles

Faubourg Saint-Marcel Workshop, Paris , workshop Monogrammist 'FM' , workshop attributed to Antoine Caron (1521 - 1599), designer

References

Denis, 2011: ‘A New Look at the Story of Coriolanus’, in Thomas Campbell and Elizabeth Cleland (eds.), Tapestry in the Baroque: New aspects of production and patronage, New Haven and London 2011, pp. 34-55 Brejon de Lavergnée and Vittet, 2007: Arnaud Brejon de Lavergnée and Jean Vittet, à l'Origine des Gobelins, La Tenture d'Artémise, La redécouverte d'un tissage royale, exh. cat. Galérie des Gobelins, Paris 2007 Auclair, 2000: Valérie Auclair, ‘De l’example antique à la chronique contemporaine. L’histoire de la Reine Artémise de l’invention de Nicolas Houel, in Journal de la Renaissance, vol. 1, pp. 155-88 Denis, 1999: Isabelle Dénis, 'Henri Lerambert et l'Histoire d'Artémise. Des dessins d'Antoine Caron aux tapisseries', in La Tapisserie au XVIIIe siècle et les collections européennes, Paris 1999 Adelson, 1994: Candace J Adelson, European Tapestry in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis 1994 Denis, 1992: Isabelle Denis, 'L'Histoire d'Artémise, commanditaires et ateliers. Quelques précisions apportées par l'étude des bordures', Bulletin de la Société de l'Histoire de l'Art français, 1991, pp. 21-36 Volk-Knüttel, 1976: Brigitte Volk-Knüttel, Wandteppiche für den Münchner Hof nach Entwürfen von Peter Candid, Munich 1976 Ehrmann, 1964: Jean Ehrmann, ‘Antoine Caron: "Tapisserie et tableau Inédits dans la Série de la Reine Artémise"', Bulletin de la Société de l'Histoire de l'Art français, 1964, pp. 25-34 Fenaille, 1903-1923: Maurice Fenaille, État général des tapisseries de la Manufacture des Gobelins depuis son origine jusqu’à nos jours, 1600-1900, 4 vols., Paris, 1903-1923 Niclausse, 1948: Juliette Niclausse, Tapisseries et Tapis de la Ville de Paris, Paris 1948