The process of dismantling and moving a large piece of furniture provides an unrivalled opportunity to examine it closely. Sabine Winn's ‘secretary’ is a case in point.

The ‘secretary’ [Figure 1] was supplied in two phases in 1766 and 1767, not for Nostell Priory, but for the Winns' London house at 11 St James’s Square.

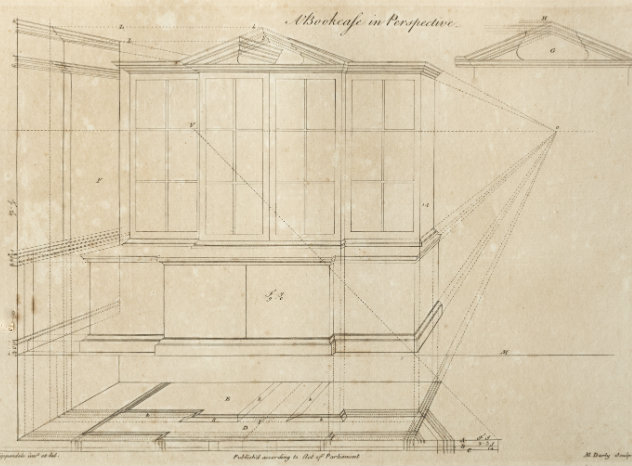

Surviving bills and correspondence show that this writing desk and bookcase was commissioned in two phases. The central cupboard appears in accounts on 24th June 1766 as:

'a Lady’s Secretary of fine Mahogany with a Bookcase on the top with drawers & pidgeon holes & a Scro’l pediment & c...25 0 0'. [1]

A very fine piece of furniture, it is comparable in form to a similar writing desk and bookcase supplied to Paxton House, Berwickshire, but it is finished with a higher grade of fittings: its handles are Chippendale’s finest pattern, the drawers elegantly crossbanded and the pediment beautifully carved. This desk and bookcase has been said to illustrate Chippendale's 'seemingly effortless ability to achieve the sober dignity and sincerity which English patrons so much admired'. [2] Its restrained ornament, beautiful proportions and high quality timber are typical of much of Chippendale's work for the Winns. Nevertheless, in February 1767, Chippendale billed for supplying ‘2 very neat Mahogany Cupboards made of fine wood to stand on each side of the secretary...£5 5s 0d'. [3]

A discrepancy

Oddly, however, the two flanking cabinets are completely different sizes, there being a 3.5cm difference in height between them, the discrepancy being in the depth of the drawers and their apertures (Figure 2). The height of the cabinets is identical up to the moulding which separates the doors from their drawers above. This asymmetry has gone unnoticed, not least because the room in which the piece now stands is not large enough to view the cabinet frontally, which is how the difference becomes apparent.

Figure 2: The flanking pedestal cabinets of Sabine Winn’s ‘secretary’, shown detached and side by side, and noticeably different heights

Figure 3: The pedestal drawers of Sabine Winn’s ‘secretary’ removed and photographed side-by-side

The reason for this difference is not clear. Furniture was sometimes made with differing dimensions in the feet, for instance, to allow for an uneven floor, but this does not explain why these pedestals are a different height in the drawer, particularly when the line of the top of one coincides – when standing in the room it now sits – with the line of the dado, whilst the other sits some way beneath it. Any discussion as to why these cabinets were made to be a different height is hampered by the fact that there is no surviving material to suggest why the Winns asked for this modification to be made. There is also no evidence in letters – and Sir Rowland could usually be relied upon to complain of any fault – to suggest that the Winns were unhappy with the result.

It could have been a mistake. Other furniture at Nostell Priory – a commode and a clothes press – are known to have been altered subsequent to their arrival at the house because they didn’t quite fit the places for which they had been made. It could be that the flanking cabinets were each made by a different craftsman. This seems unlikely, since the drawers from each cabinet were almost certainly made by the same man (Figure 3).

Alterations & Repairs

Whatever the reason for this discrepancy, it isn’t the only idiosyncrasy. The central cabinet of the 'secretary' was already with the Winns when the flanking cabinets were ordered. It was a finished piece of furniture, with decorative applied mouldings to the sides around which the pedestal cabinets would have to be fitted (Figure 4). The fitter did not remove these elements from the main piece but, instead, modified the flanking cabinets (Figure 5), ploughing a groove into their deal sides. To accommodate the base moulding, sitting just above the bracket feet, also on three sides of the main cabinet, the fitter simply shaved away the pedestal's bottom edge, in the process ploughing through the dovetails joining the pedestals’ sides to their bottoms. This compromised their stability, causing the base of each cabinet to drop.

After the passage of such a long period of time, this weakness could perhaps be forgiven, but it wasn’t the first time this 'secretary' had required expenditure on repairs. On 28th March 1767, Chippendale billed the Winns 7s 6d for ‘2 new locks and repairing a lock and fixing them on a Secretary and easing the drawers of ditto’, probably a reference to this desk and bookcase. Just under two years later on 25th February 1769, he charged 1s 6d for ‘Easing the drawers of Lady Winn’s secretary’. [4]

The first of these entries probably explains the very evident repairs to the lower part of the central writing cabinet. When the flanking pedestal cabinets were attached, they were screwed directly into the mahogany sides of the lower case, necessitating – if they were to lock – the drilling of sockets to accommodate bolts. This was successfully done on one side, but to the other there is a lozenge-shaped patch (Figure 6) suspiciously close to where a socket may have erroneously been drilled.

Figure 6: The left proper end of Sabine Winn’s ‘secretary’, showing a lozenge-shaped patch

Notes

[1] West Yorkshire History Centre, WYW1352/3/3/1/5/3/63.

[2] C. Gilbert, The Life & Work of Thomas Chippendale (2 Vols., London, 1978), Vol. I, p. 171.

[3] WYW1352/3/3/1/5/3/63.

[4] Ibid.