Two pieces of mahogany furniture at Nostell Priory, which have hitherto been tentatively attributed to Chippendale’s workshop, but which are different to other pieces of his documented furniture in the house, reveal intriguing similarities, suggesting that they were made by the same hand.

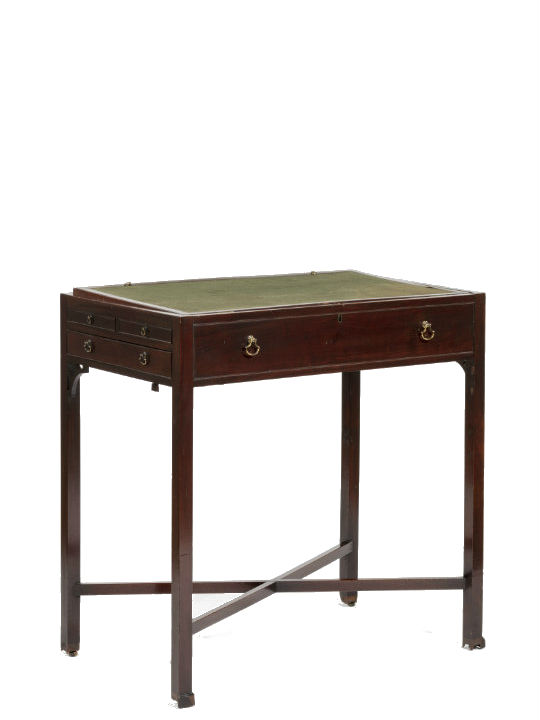

The first of them is now called a ‘clerk’s' desk (Figure 1), designed for use whilst standing, the second is an ‘artist’s' table (Figure 2), for drawing or writing, with a baize-lined writing surface beneath a solid mahogany top.

The 'clerk's' desk

When the former's hinged top is raised, the front board (comprising three false drawer fronts delineated with cockbeading as well as the sections which form the arch) slides upwards in grooves and comes away in one piece. This exposes the writing surface, unusually made of chestnut, inside (Figure 3). Idiosyncratic in the extreme, this desk may have been made to order.

Figure 3: Detail of the 'clerk’s' desk, with slope and front board removed

The 'artist's' table

The hinged mahogany top of the 'artist's' table sits atop a surface still lined in its original 'green cloth' or baize. This surface is, in turn, hinged, and can be set at an angle on a hinged, easel-type support fitted to its underside, which adjusts on grooves beneath it. Its very plain legs were once embellished with applied mouldings forming block feet and concealing castors, although many of these have now come away, and the original effect obscured. The long drawer in the front frieze is false, but one end frieze is fitted with both a drawer and a beautifully-made swinging ‘compartment’ fitted with ivory palettes for mixing paints (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Detail of the 'artist’s' table, showing the palette 'compartment'

The two compared

Both are made from a dense mahogany which has darkened over time to a very dark brown, and both employ cockbeading – around both true and false drawers – as the main decoration to relieve otherwise flat planes of timber. In addition, the legs of both are simply square-section, with no chamfer or other refinement. The holly or sycamore used to line drawers in both pieces is distinctive, and suggests that the two were probably made by the same hand. Most significantly, perhaps, the drawers to both are not fitted with locks but instead are secured by pins, accessible only when the main compartment of the piece is unlocked. Each pin slides through holes drilled through the top and bottom of drawer fronts, and through the rails which separate them (Figures 5 & 6).

Figure 5: Detail of the underside of one of the drawers of the 'clerk's' desk, showing sycamore or holly linings, and the hole for a securing pin to the underside of the drawer's front

Figure 6: Detail of the 'artist’s' table, showing holes for securing pins through the compartment’s front and the rail above it, both inaccessible when the piece’s mahogany top is locked, and the pale sycamore or holly drawer linings

This security measure was employed where an external drawer front – not itself concealed behind a locking door – was too small to accommodate a lock. It does not appear on any other pieces of documented furniture at Nostell Priory. Perhaps they were made by a cabinet maker who specialised in furniture designed for a specific past-time, who favoured this type of locking mechanism?

Figure 7: Detail showing the interior fittings of the ‘clerk’s' desk; the labels to the drawers read ‘Tape’, ‘Sealing Wax’ and ‘Wafers’

Documentary evidence

The ‘clerk’s' desk is probably the piece of furniture that appears in a bill submitted by Chippendale for the London house, 11 St James’s Square, on 23rd June 1766 where it is described as ‘A large Mahogany Case for papers to stand on a Frame with Drawers, Pidgeon Holes, divisions for books’ and costing £13 10s. [1]

The ‘frame’ refers to the open, high base and the desk section matches the description, being fitted with small drawers and central pigeonholes. In addition, the character of the handles to the interior conforms to handles used elsewhere by Chippendale. The desk diverges from the description, however, in its lack of ‘divisions for books’. However, in inventories of 1806 and 1818, a ‘writing desk on frame’ is recorded in the Stone Parlour or Muniment Room at Nostell Priory, compelling evidence, given that the term ‘on frame’ is repeated, that the piece of furniture made by Chippendale for 11 St James’s Square had made its way to Nostell Priory by the early 19th century.

There is no convincing match for the artist’s table either in Chippendale’s bills or in his correspondence with Sir Rowland, but it is very likely that whoever made the ‘clerk’s' desk also made the ‘artist’s' table: a craftsman who used sycamore or holly in drawer linings and favoured drawers secured by pins.

If the ‘clerk’s' desk is one and the same as the ‘large Mahogany Case for papers to stand on a Frame’ made by Chippendale’s workshop for the Winn’s London residence in 1766, then the artist’s table must surely be attributable to Chippendale’s workshop too. If it isn’t, then they are possibly evidence for the Winn’s commissioning furniture from another cabinet-maker at about the same time as they were commissioning work from Thomas Chippendale.

Notes

[1] West Yorkshire History Centre, WYW 1352/3/3/1/5/3/63.