Collecting ceramic treasures has been fashionable in Britain for over 400 years. In the 19th century, significant private collections were published and exhibited, and specialist study societies formed. By the early 20th century, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum were home to some of the finest ceramics in the world.

Mrs Greville’s own collection of about 500 pieces includes equally important East-Asian and European examples, dating from the 7th to 20th centuries. Below are examples from her collection of Chinese ceramics, Meissen porcelain, Italian Maiolica and British pottery.

Chinese ceramics: Earthenware and Porcelain

Chinese porcelain began to be brought to Europe in substantial quantities from the beginning of the 17th century. It was admired for its hardness, bright colours, and sophisticated decoration, and over the next few centuries tens of millions of pieces were imported.

By around 1900, there was a renewed interest in East Asian ceramics in Britain. This was fuelled in part by the Aesthetic Movement, which encouraged a greater focus on visual beauty, and in part by the increased Western access to China and Japan in the heyday of imperialism.

British and other Western collectors were not just acquiring Chinese and Japanese porcelain made for the West, but also types of objects that had not been seen in the West before. These included porcelain vessels made for the Chinese court, as well as funerary models placed in tombs.

On the one hand, the collecting of these new categories of objects reflected the Western global dominance at this time. But on the other hand it also demonstrated a genuine admiration for ‘authentic’ Chinese art and material culture.

Earthenware

These earthenware horse heads were originally part of funerary models, known as ‘spirit utensils’ (冥器 mingqi), figures of servants, household animals and furniture placed in tombs to furnish the afterlife. These heads may date to the 5th or 6th century or the Tang dynasty (618–907). Mingqi entered the international art market in the early 20th century, as railways were being built across China and numerous tombs were being discovered.

Porcelain

The porcelain figures below are decorated with various enamel colours on the biscuit (or unglazed surface). They were probably made in the Chinese porcelain production centre of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province during the Kangxi period (1662-1722). The enamel colours typical of this period, which include shades of green, were later called famille verte or ‘green family’ by Europeans.

Buddhist lion and her cub

Images of lion guardians came to China from India in the third century, along with the introduction of Buddhism. But as Chinese artisans had never seen real lions, the versions they produced in stone and porcelain tended to look playful rather than fierce.

Figures representing Guanyin

Guanyin is a Chinese version of an Indian Buddhist bodhisattva, a figure who helps others achieve enlightenment. Originally male, Guanyin came to be worshipped as a goddess of mercy in China. But these religious meanings were lost in translation when these figures came to Europe, and they had a mainly decorative role in British interiors.

Figure representing Guandi

This figure represents Guandi, a god of war and protector against demons. He is the deified form of a bean curd peddler called Guan Yu, who is said to have lived in third-century China and became famous because of his heroic feats.

A man leading a packhorse

This porcelain figure of man leading a packhorse may be a travelling merchant. The enamels with which he is decorated echo the ‘three colours’ (三彩 sancai) glaze palette of Tang-dynasty ceramics. That colour scheme was revived in the Kangxi reign, c. 1700, as a deliberately antiquarian style.

Pair of tureens in the shape of geese

These porcelain tureens in the shape of geese are decorated with enamels that were later called famille rose or ‘pink family’ by Europeans. These began to be used on Chinese porcelain in the 1720s, and were ironically called ‘foreign colours’ (洋彩 yangcai) by the Chinese, as some of the enamel technology had come from Europe.

The fashion for animal- and vegetable-shaped tureens is associated with European taste, possibly inspired by animal tureens produced in Strasbourg from about 1750. It seems likely that the Chinese porcelain suppliers responded to European demand for such tureens by modelling them on a local breed of goose, probably the Chinese swan goose (Anser cygnoides).

But geese are also significant in the Chinese pictorial tradition, being a symbol for peace, prosperity and marital fidelity. The fourth-century calligrapher Wang Xizhi (王羲之) is said to have improved his writing technique by watching geese move their necks.

European Ceramics

'White Gold': Meissen Porcelain

European ceramics makers did not know how to produce ‘true’ porcelain of the East Asian type until about 1710, when the Meissen factory in Germany developed their own version of the so-called ‘white gold’. The pieces they made were often decorated with scenes emulating Chinese and Japanese art.

The pieces below are decorated in the ‘chinoiserie’ style of the talented Meissen designer Johann Gregorius Höroldt who created this combination of fantastical East-Asian scenes framed within European, Baroque-style, borders. Höroldt established a large painting workshop at the factory, training apprentices to paint in his style by copying from the almost 1000 drawings in his own sketchbooks.

Maiolica

The name maiolica was first used by Italians to describe Spanish tin-glazed earthenwares produced from the fourteenth century onwards. It is thought the term derived from the early places of production in Malaga and the export route to Italy via the island of Mallorca. When Italian potters began producing their own tin-glazed earthenwares they also called these ceramics maiolica.

Duck and parrot

Mrs Greville was friends with Henry Harris (c.1870–1950), a maiolica enthusiast and Tancred Borenius (1885–1945), a Finnish art historian. Harris and Borenius advised her on purchases and influenced her taste in the formation of her collection of maiolica which she acquired between 1925 and 1935, originally for her house in London but now at Polesden Lacey.

Ewer

This ewer was probably made in Lyon, France by Italian potters during the third quarter of the 16th century. It is modelled with three moulded grotesque masks and with a lion's mask below its one handle. It is decorated with a biblical scene from Genesis, taken from an engraving in Bernard Solomon's Quadrins historiques de la Bible, a book of biblical illustrations published in Lyons in 1553.

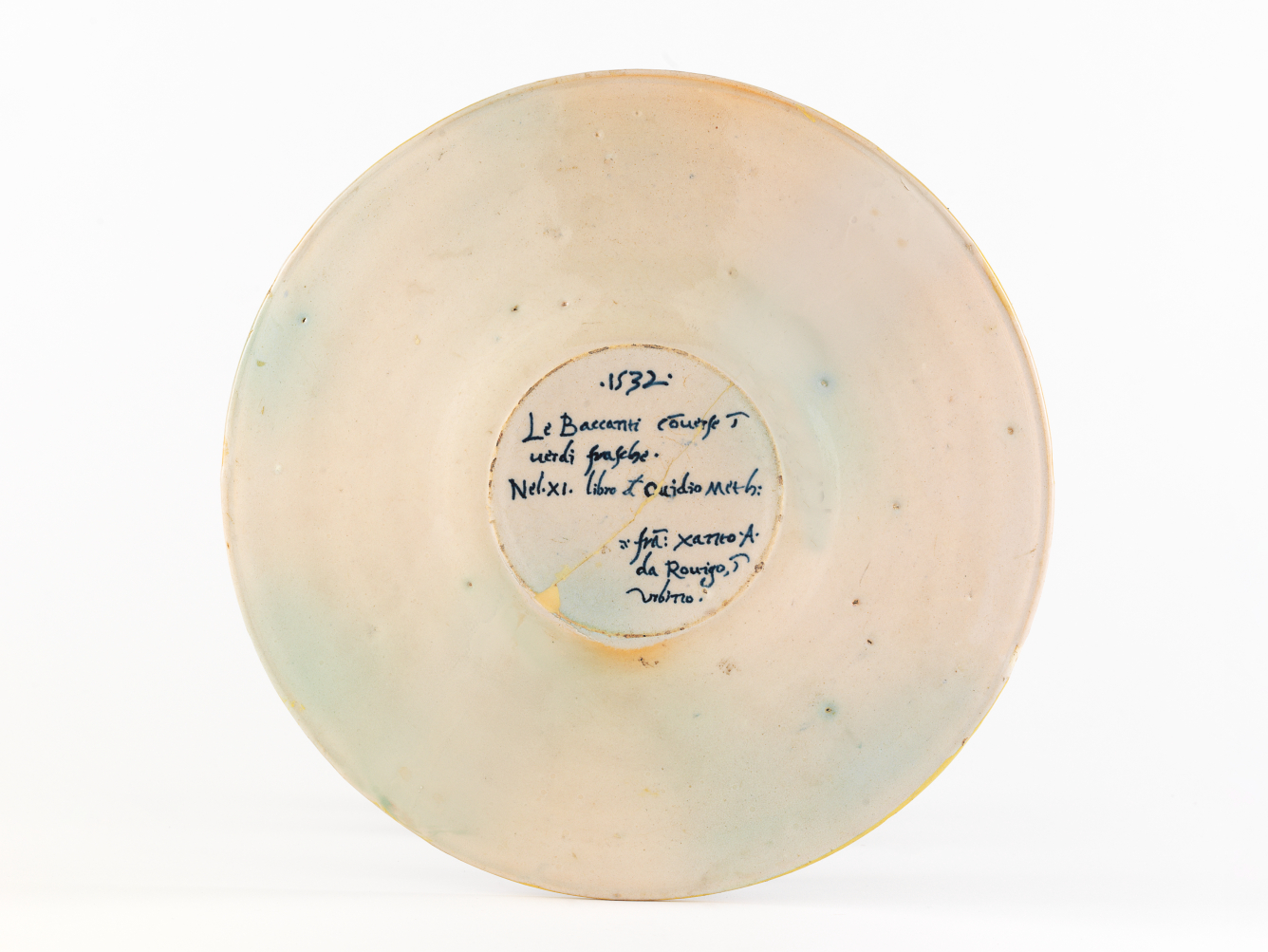

A dish signed by Xanto

This dish, by the maiolica painter Francesco Xanto Avelli of Rovigo, known as Xanto (1486–1542), is one of the first pieces of European ceramics signed by any artist. It is part of the largest table service (credenza) Xanto ever made, for the powerful Pucci family of Florence, depicting scenes from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’. The arms of the family, on this dish, include the stereotyped head of a person of colour of a type that frequently appeared as a motif in European heraldry.

It is one of twenty-three pieces of Italian Renaissance maiolica at Polesden Lacy, four of which are signed by Xanto. A dispute over wages may have prompted him to begin signing his works – an extraordinary act at the time.

Mrs Greville's tulip collection

By the middle of the 19th century, tulips were so popular that many towns had a specialist society for growing and showing the flowers. British and European ceramics manufacturers created artificial tulips, painted with bright enamels, to provide year-round colour on the table or mantelpiece. Mrs Greville's own collection of tulips was displayed in her bedroom at Polesden Lacey.

Tulip dish and cover

hard-paste porcelain, painted and glazed

Probably made by the Rudolstadt-Volkstedtt factory, Thuringia, Germany, 1760–90

This dish is the earliest piece in Mrs Greville’s ‘Tulip Collection’. It was made in the 18th century when fantastical shapes of porcelain were made to imitate nature. Probably for an individual portion, perhaps for dessert, the dish may have been one piece of a larger set laid out to create the effect of strewn flowers.

Tulip ornaments

lead-glazed earthenware, painted

made in Staffordshire, England, about 1820–30