With 34 fully documented chairs – and a further 23 which are generally agreed to have been made in Chippendale's workshop – one might assume that the seat furniture at Nostell Priory would provide an accurate record of the construction of chairs in Chippendale's workshop. Unfortunately, the original appearance of most of the chairs at Nostell Priory has been obscured by later alterations, particulary in the case of upholstered chairs.

Sir Rowland Winn and his wife, Sabine, as was customary, covered their chairs in opulent fabrics in colours which matched or complemented wall-hangings, floor coverings, and curtains.

The selection of textiles was such an important part of interior decoration that Chippendale and, on occasion, Robert Adam, dictated what colours and textures would be most appropriate, and these details are preserved in surviving documents. Thus, the chairs made for Sabine Winn’s dressing room were to be covered in ‘blue morine’ (Figure 1), chairs for the Library in ‘green hair cloth’ (Figure 2) and ‘black leather’ and ‘French Elbow chairs Cov’d with horse hair and Double Rows of brass Nails’. [1]

Now, however, the chairs made for Sabine Winn's dressing room are covered in red leather (Figure 1) and the library chairs in red horsehair (Figure 2). In truth, most sets have probably been re-covered several times since first supplied. Not only then, is their appearance obscured, but later changes also mean that constructional details are no longer visible.

All of the chairs and sofas with overstuffed seats at Nostell Priory have been fitted with springs beneath the seats, in turn concealed by base cloths. As a result, in many cases the chairs’ seat rails – the parts of a chair which form the seat, and to which the legs and arms supports are joined – are not visible from the underside. The set of eighteen pieces of green-japanned seat furniture, supplied by Chippendale in 1771, have been both re-upholstered and sprung (Figures 3 & 4) and so too have the chairs and sofas supplied circa 1778 (Figures 5 & 6).

Figure 3: One of the green-japanned stools supplied in 1771

Figure 5: One of the painted and parcel-gilt chairs supplied by Chippendale, circa 1778

Figure 4: A view of the underside of the stool, with later base-cloth

Figure 6: Rear view of one of the painted and parcel-gilt chairs supplied by Chippendale, circa 1778, showing the central upright strut to the back

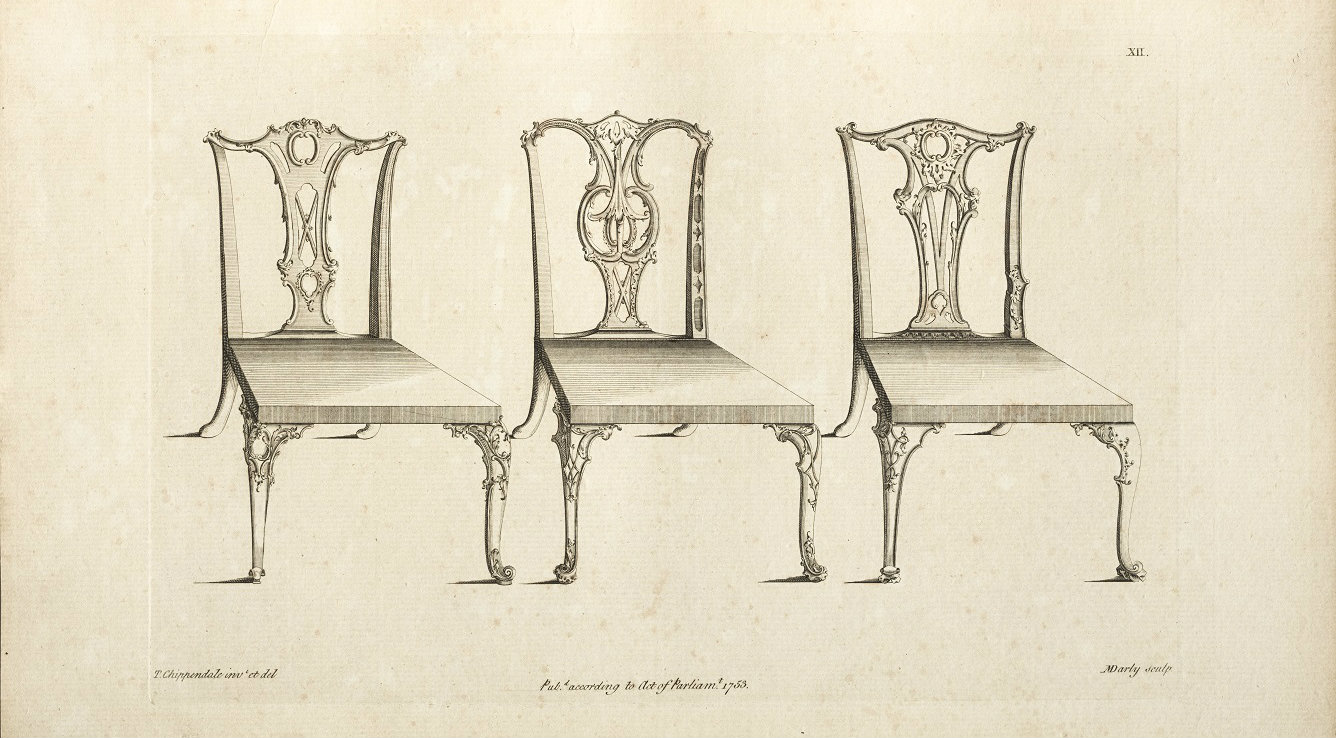

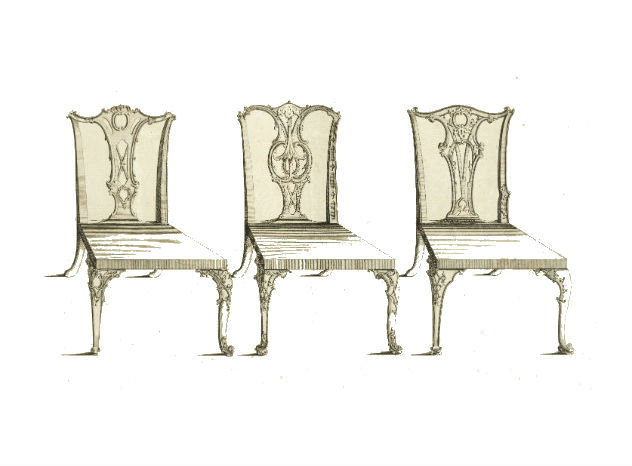

Fortunately, this is not the case with the chairs which have covered seat pads, which ‘drop in’ to sit within the chair’s seat rails, also known as ‘slip seats’. The set of chairs (Figure 7) which is attributed to Chippendale because they are a very close match to a design published in Chippendale’s Director in 1754 (Figure 8) have – like the library chairs in Figure 2 – had their seat pads recovered, but the pad can still be removed and the chair’s construction revealed (Figure 9). The seat pad is supported both on the front legs, the inner corner of which has been cut away, and by glued solid angled corner blocks.

By contrast, the Library chairs in Figure 2, which also have a seat pad which ‘drops in’ to the seat rails, were made differently. Instead of having a section of the front leg cutaway, the glued and elegantly-curved beech corner blocks have an angled cut-out so that they abut the top of the leg itself (Figure 10). Blocks with this curved profile were more typical of 19th century, rather than 18th century, chair-making, so it is possible that these are later additions or replacements.

Figure 9: Figure 3 with the seat pad removed, showing the solid corner blocks which support it, the internal chamfer of the legs, and the moulded seat rails

Figure 10: Detail of the library chairs, with the seat pad removed, showing shaped beech brackets

© National Trust / Megan Wheeler

Another set of chairs made by Chippendale at Nostell Priory, even though entirely made of wood and with no upholstery liable to tampering, have still not escaped later ‘improvements’. The set of eight carved limewood and beech hall chairs in the Top Hall (Figure 11), attributed to Chippendale on the basis of their similarity to chairs at Harewood House, to which Chippendale also supplied furniture, were originally white, but re-painted to resemble oak in 1821. Nevertheless, with solid seats, they have not suffered other obfuscating replacements, and it has been possible to take meaningful photographs of them from previously unseen angles.

A photograph of the same hall chair from the back (Figure 12) shows the method by which the board which forms the back is tenoned into the rear seat rail, to which the leg blocks are also fixed. A repaired break to the rear right-hand upper leg block demonstrates – in common with most chairs of this type – the inherent weakness in this type of joint, the load-bearing space between the two back legs being relatively small. This picture also shows how the supports for the arms join the seat rails from the side, and sit proud of it, a characteristic feature of Chippendale chairs which is also found on the lyre-backed chairs made for the library (Figure 2).

Figure 13: The underside of the hall chair

A view of the chair’s underside (Figure 13) shows the seat rails, the additional block glued behind the rear seat rail and the screws with which the rails have been secured. There are several later replacements to both screws and the carved mouldings which skirt the leg blocks.

Notes

[1] L. Boynton & N. Goodison, ‘Thomas Chippendale at Nostell Priory’, in Furniture History 4 (1968), 19 – 20; C. Gilbert, The Life & Work of Thomas Chippendale (2 Vols., London, 1968), Vol. I, pp. 180 - 182.