The Child family arrived at Osterley during an 18th-century financial boom. Empty and unfinished, the house was acquired in 1713 by Sir Francis Child the Elder (1642–1713) to make the best of an unpaid loan he had made to its previous owner, a near-bankrupt property speculator.

Osterley became the country retreat of Francis’s three sons, Sir Robert, Sir Francis the Younger and Samuel. Each in turn ran the family’s bank on London’s Fleet Street.

The Childs thrived during a time of radical economic change known as the Financial Revolution. They invested heavily in London’s emerging stock market and competed with the newly-founded Bank of England to lend to the government at high rates of interest. As other bankers and speculators fell prey to the era’s booms and busts, the Childs went from strength to strength.

London Landmark

The Childs’ bank was situated on Fleet Street next to the Temple Bar. This was a stone gate that marked the boundary between the commercial City of London, where the family invested in the stock market, and the emerging West End where many of their aristocratic customers lived.

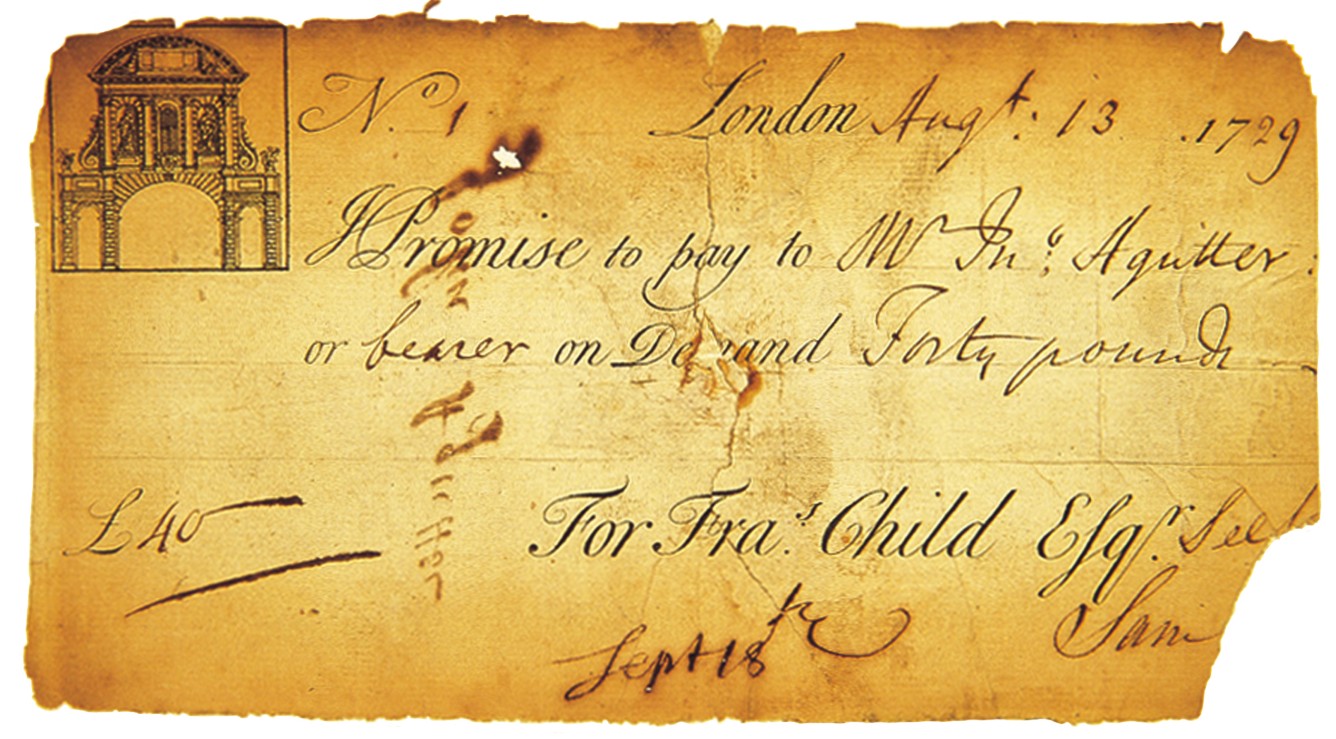

The bank used the room over the Temple Bar archway to store its records. In time it adopted the landmark as one of its symbols.

In 1729 the bank issued its first printed bank note which features Temple Bar in the top-left corner

Reproduced by kind permission of RBS © 2019

A modern bank?

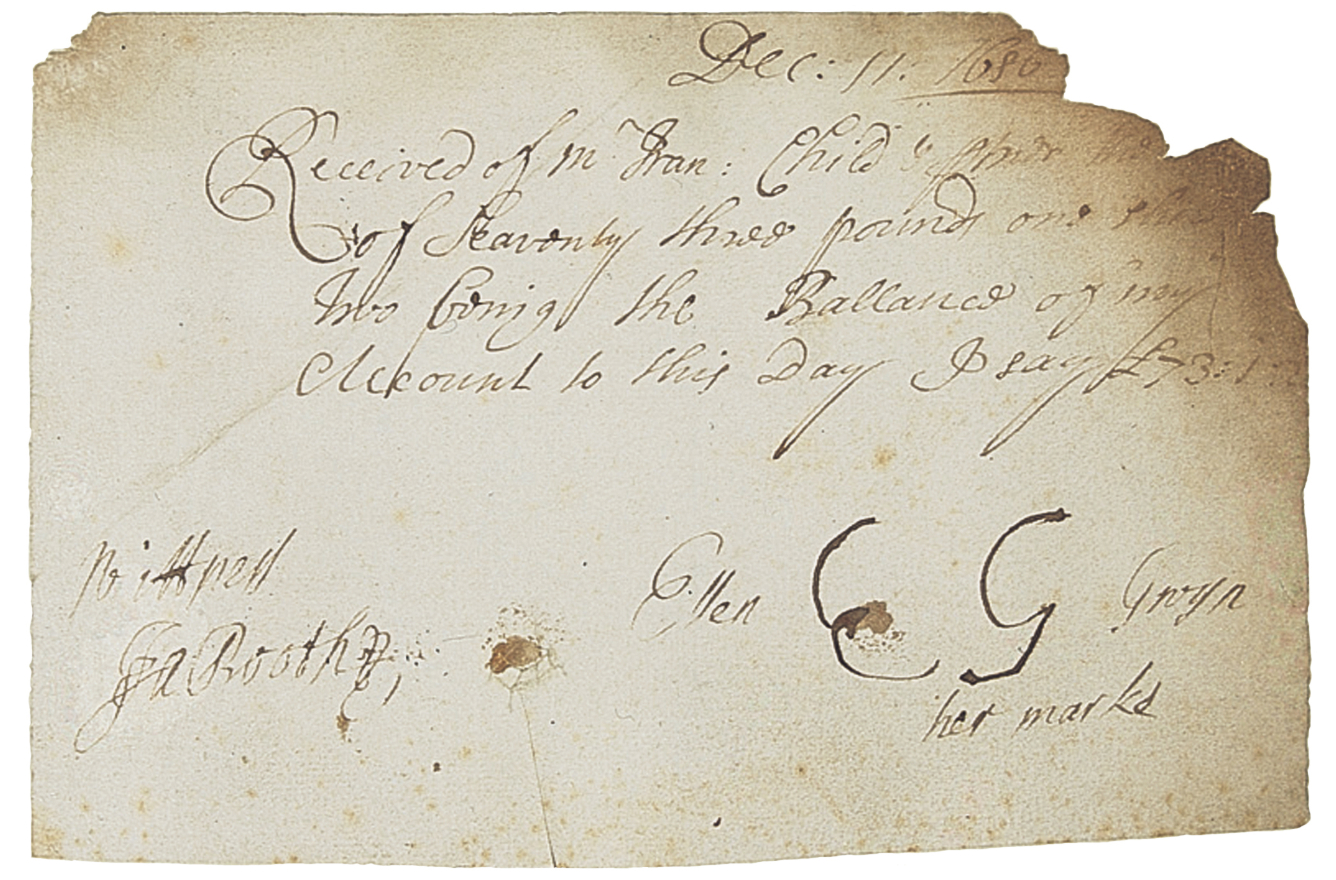

The Childs’ business on Fleet Street was arguably one of the first modern banks in Britain. For the first time you could open a current account, take out a loan and withdraw paper money all under one roof. Sir Isaac Newton and the monarchs, William and Mary, were among the Childs’ many famous customers. Even Nell Gwynn, Charles II’s mistress, had an account.

A receipt for money received from Francis Child the Elder by Nell Gwyn, signed with her marks.

Reproduced by kind permission of RBS © 2019

Francis Child the Elder (1642–1713) began his career as a goldsmith but by the end of his life almost all his business was banking. This change took place because the Childs, like other London goldsmiths, had strong rooms where customers could leave cash for safekeeping.

An engraving showing customer transactions in the Bank of England, c.1694. It features a typical iron strong box used by bankers.

© Bank of England

They began to profit from this money by lending it to others for a fee. In addition, they were willing to cash cheques and issue banknotes promising to repay deposited funds. These began to circulate in everyday life as a convenient substitute for metal coinage. All the Childs had to do was hope that their customers would not all ask for their money at once, causing a ‘run’ on the bank.

Financial Revolutionaries

Sir Francis Child the Elder and his sons prospered in an age of economic innovation that left many baffled and suspicious. The writer Daniel Defoe negatively labelled Sir Robert one of the era’s 'Jobbers & money’d Men' whose complex dealings seemed to allow him to profit at the nation’s expense.

Financing the war – Sir Francis the Elder lent extensively to the government during an expensive war with France in the 1690s. When the Bank of England was founded in 1694 to supply credit to the government he treated it as a rival. This period was the beginning of an ongoing national debt that today stands at £1,807 billion.

Playing the stock market – The Childs invested heavily in London’s new stock market. They were major shareholders in the East India Company which controlled British trade in South and East Asia and eventually led to imperial rule. In 1713 Sir Robert was also involved in the financial dealings of the South Sea Company which transported enslaved Africans to Spain’s American colonies. Seven years later the overinflated value of shares in the Company collapsed: the burst of the South Sea Bubble.

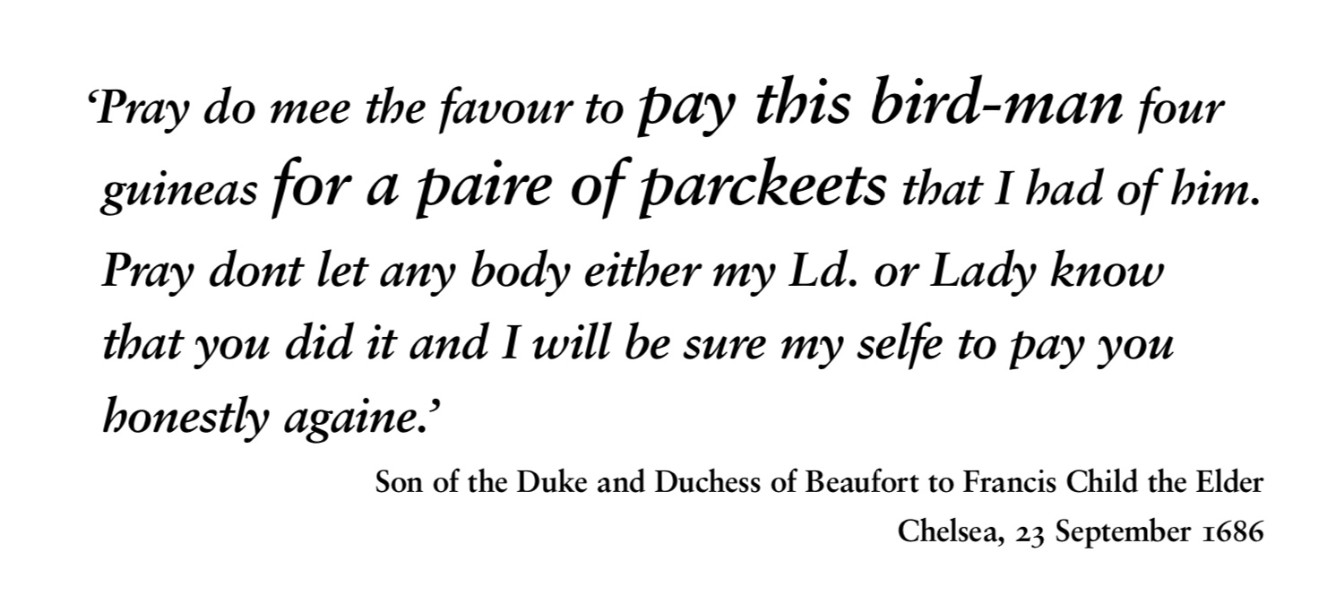

Running lotteries – The family business appealed to the age’s love of luxury and gambling. In the 1680s they ran lotteries in which the prizes were jewels and Chinese porcelain.

Security

Iron strong boxes were an early form of safe used by the Childs and other bankers to store money and precious objects. In 1691, Francis Child the Elder was accused in the law courts of stealing diamonds and pearls that Charles II’s mistress, Nell Gwynn, had entrusted to him before her death. His answer was that these jewels were left as security against large loans which she never repaid. They remained in his London bank 'locked up in a strong box', which may have been very much like this one.

Politics

The Childs held high political offices in Parliament and the City of London to protect the interests of their bank and the wider business community. When Francis the Elder was elected Lord Mayor in 1698, he was given this silver dish by the Jews of the city’s Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue.

The dish would have been piled high with confectionary and accompanied by cash. The gift totalled c.£16,000 in today’s money: a precautionary bid for protection at a time when anti-Semitism was commonplace.

The dish is chased with a scene, taken from the synagogue badge, depicting a guard standing beside Abraham's tent. Below the tent is an engraved motto which reads ‘The arms of the Tribe of Judah given them by the Lord’. These words are also taken from the badge of the synagogue but may also have been a reminder to the incoming Mayor of the special status granted by God to the Jews.

Global Trade

Francis Child the Elder and his sons were major shareholders or Directors of the profitable East India Company based in the City of London. This was the only business permitted by the government to import goods from South and East Asia. Some of their most precious imports were Chinese porcelain made for serving punch. Robert admired the transparency of Chinese porcelain which he said gave it ‘the advantage’ over European imitations.

This large punch bowl (above) may have been made for the Indo-Islamic market in South East Asia suggested by the gilt decoration on the powdered blue ground, but arrived in England as incidental trade. European merchants were always on the lookout for curious patterns and novelties. The translucent overglaze enamel pigments are in the so-called 'famille verte' palette, which was a refinement of the 'wucai' (five colour) enamels popular throughout the 17th century.

Japanese imports like this punch bowl (above) made in the kilns in Arita, in Hizen province, on the Island of Kyūshū, had to be acquired via contacts in Holland or China which were the only nations permitted to export from Japan at that time. The designs on the bowl – window blinds tied back to reveal autumnal branches of maple leaves and pine branches – are adapted from those produced for local customers. The large bowl shape, however, was probably made for export to the West.

European trade with East Asia changed the way Chinese porcelain was produced. This rare punch bowl (above) is decorated with courtiers hunting deer, waterfowl and a leopard. It was painted in the port of Guangzhou (Canton), the hub of Chinese exports, using a novel range of opaque pigments. These were known as yangcai (‘foreign colours’) and were inspired by European enamels.