In the mid‐17th century, decorated papers began to be used in the English bookbinding trade to add a splash of colour to otherwise uniformly brown bindings.

In 1662, John Evelyn delivered a famous lecture to the Royal Society in which he recounted how marbled paper was made. Although early examples can be found on books bound in England from the 1650s, coloured and decorated papers began to be used more commonly for covering the boards of books, and for wrapping smaller volumes in their entirety, from the 1670s onwards. By the 1730s, the practice was widely adopted by the trade and decorated papers migrated from the outsides of books to the insides, used as pastedowns and endpapers.

There is a bewildering array of different types and styles of decorated paper, most originating on the Continent. Marbled paper alone has its own classification system, with variations ranging from Old Dutch, French Shell, Stormont Antique Spot and Nonpareil.

This article presents a selection of decorated papers from the library at Nostell Priory in Yorkshire as a means of introducing some of the different types of papers used in different periods.

Nostell Priory: a treasure trove of decorated papers

The library at Nostell Priory has its roots in the 16th century, but the bulk was acquired between the mid-17th century and the mid-19th century – a period when decorated papers on books moved from being an oddity to being ubiquitous.

Three features of the Nostell collection make it particularly interesting for the study of decorated papers. The first is its location. Nostell is just 25 miles south of Fulneck, a small Yorkshire town near Pudsey which was the site of a remarkable and pioneering paper decorating industry in the 1760s and 1770s.

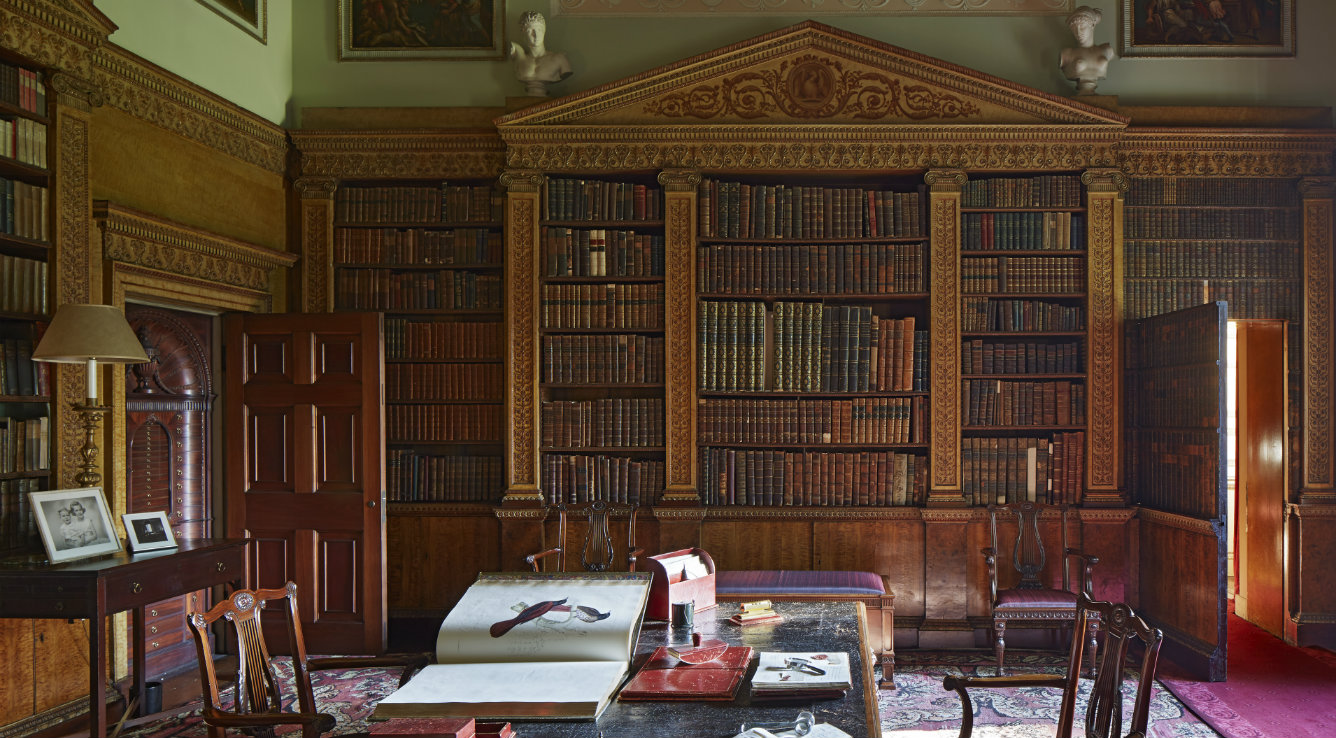

The second is its architectural history. Planning for the construction of the current house began in 1729, right at the moment decorated papers started to be widely used in the bookbinding trade. The glorious library room at Nostell was constructed in the 1760s to plans drawn up by Robert Adam. It was furnished by Thomas Chippendale and decorated by Antonio Zucchi and Joseph Rose the Younger, and its construction was accompanied by a period of fevered book acquisition and bookbinding by the Winn family in order to fill the new shelves with appropriately gilded books. So, at precisely the moment when the Fulneck paper decorators were beginning to supply local binders with their wares, the Winn family at Nostell were keeping those binders very busy indeed.

The Library at Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire

©National Trust Images/Dennis Gilbert

The third feature of Nostell’s library which impacted on its decorated papers was the arrival of Sabine d’Hervart (1734-1798). The wife of Rowland Winn (1739-1785), 5th Bart., Sabine was the daughter of a Swiss aristocrat of Huguenot descent, Jacques Phillipe d’Hervart, Baron de Saint-Légier and Governor of Vevey (1704-1764). On her arrival at Nostell she brought with her a dowry which included furniture, linen, paintings, cheese and books. These books, the remnants of her family’s library, stretched back to the early 16th century. The bindings are unlike anything else one might find in an English country house, indeed in any English library, and they use a variety of distinctive decorated papers.

Decorated papers in English bindings

The use of decorated papers in English bindings began in the mid-17th century, and Nostell has a number of early examples.

Bronzefirnispapier

Nostell's copy of Marcus Aurelius's Meditations in Latin and Greek was bound in England in full vellum soon after publication in London in 1697. The front and back boards were then decorated with a type of paper known as Bronzefirnispapier (bronze varnish paper), simply cut to size and pasted on. Printed using wooden blocks, this Bronzefirnispapier mimics the brocades and damasks of the period and was probably imported from Germany.

The book itself came to Nostell in the early 18th century. Its first owner was Richard Bird, a student at Lincoln College, Oxford and it was passed on to Sir Rowland Winn at Nostell in 1717 by a friend. An inscription on the final printed leaf reads: 'Richard ye son of James Biscay of Sodom in ye County of York'.

Dutch Gilt paper, but not Dutch paper

Dutch gilt papers were printed by means of a wooden block or engraved rollers and started to appear on English books from about 1700. Although known as Dutch gilt, the papers were actually produced in Southern Germany and Northern Italy, but were imported into Holland, then exported by the Dutch to France and England. They are relatively common in country house libraries, mostly found as inexpensive wrappers on cheap editions and children’s books.

Here, it is found on one of the many editions of Edmond Hoyle’s guide to playing whist, three of which survive at Nostell. Many of the Dutch gilt papers found on books bound in England share this sort of floral design, coloured green, orange, red and blue.

Herrnhut paper – a Moravian import

Herrnhut paper – so named after the Moravian settlement in Herrnhut, Germany where it was first made – is manufactured using coloured pastes, a very different technique from marbled or block-printed paper.

The Moravians, followers of the Czech religious Reformer Jan Hus (c.1369 – 1415), suffered much persecution during the Thirty Years’ War. They owe their survival to a single group, which found refuge at Herrnhut and established a settlement there in 1722.

Paste papers are made by brushing a thick coloured paste made from water and flour onto a piece of paper, then producing a pattern with a finger, comb, stylus, or by sticking two sheets together and then pulling them apart.

The papers mostly follow a restricted colour pattern – crimson, Prussian blue, and dark olive green – but two and occasionally three colours could be used on a single sheet.

Herrnhut papers dominated the market in the last third of the 18th century in the eastern areas of Central Germany, but were less well-known in the south and west of the country. Were it not for the establishment of a Moravian settlement at Fulneck in 1743, Herrnhut paper would have made little impact in England. The original idea for manufacturing decorated papers in the English community came from Brother Andreas Christian Schlozer, an Alsatian who travelled to Fulneck from the Herrnhut community.

In 1766 the Elders’ Conference at Fulneck approved a request from Schlozer for the 'Single Sisters', the unmarried female residents of the community, to begin the manufacture of paste paper. The decision was made in the traditional Moravian way – two slips of paper, one yay the other nay, were placed in a ballot box and drawn, allowing the Saviour's will to be revealed. Within a year the resulting papers appeared in use in a local bindery frequented by the Winn family.

The Nostell library takes shape

The library at Nostell began to take shape in 1766,and the family were demonstrably buying books to fill the shelves, and binding books they already owned in a style more fitting for the new library.

The name of the Nostell binder is not known, but the account books of the Fulneck settlement record that in 1768 their paper was sold to Todd and Sotheran, the York bookseller favoured by the Winns, and to a Mr Mann, a Wakefield stationer. All of the books bearing Fulneck paper at Nostell are bound in a very similar style, with heavy boards covered with diced Russia calf, a single characteristic gilt roll and usually an all-over design to the spines.

The papers that decorate the 1731 English edition of Bernard Picart's The religious ceremonies and customs of the several nations of the known world, are coloured in a typically vibrant manner. The bold blue, green and crimson papers were originally intended to be used to decorate inkstands, but they were rapidly adopted by bookbinders, who saw the potential of the strikingly different aesthetic they offered.

From European import to Anglo-Moravian product

Most decorated papers used in England in the 18th century were imported. Experiments in making marbled paper here began early; in 1731 Samuel Pope was granted a patent for marbling paper, but there is no evidence that he brought his technique into practice. Henry Housman was awarded a Society of Arts premium of £50 for marbled papers in 1763, but it was not until 1788 that one Henry David set up as a commercial paper marbler in Fleet Street. The Moravians at Fulneck were, therefore, amongst the very first to attempt the craft of manufacturing decorated paper in England.

From Vevey to Wakefield

Amongst the Swiss-German books brought to Nostell by Sabine Winn are several bound in vellum, with decorated papers pasted to the boards.

Two sheets of Bronzefirnispapier decorate the front and rear of a rare little book on Roman law and its influence on Swiss law. Woodblock printed on coloured paper, the gold provides a very effective highlight.

Where this paper was made is unknown. It may have been imported from Southern Germany or Northern Italy, where the technique of making these gilt papers was well established, but it was more likely to have been sourced locally in Vevey, Neufchâtel or Berne. A very similar paper was used to bind another book printed in Berne, now in the Bibliothèque Méjanes, Aix-en-Provence.

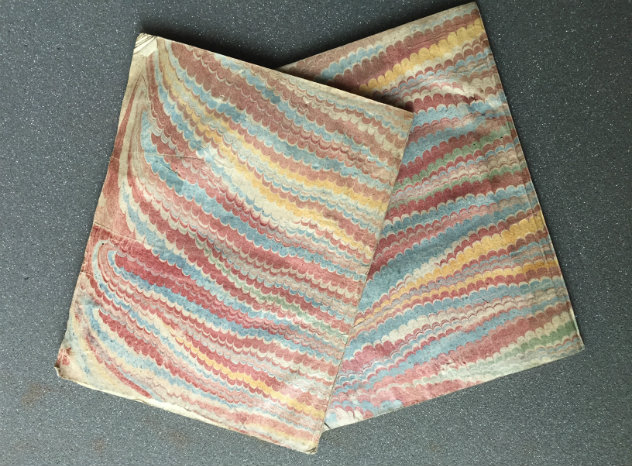

Old Dutch marbled paper - genuinely Dutch

Marbling is a technique whereby a pattern is created using paints floating on top of a viscous ‘size’. The paints are swirled or combed to create an effect; the paper is laid on top and takes an impression of the pattern.

Here, marbled papers were used in Neufchâtel in the 1730s to wrap two copies of the same pamphlet – a little Enlightenment tract on the teaching of science – by Johann Peter Conrad Stadler. Oddly, these two copies at Nostell are now the only surviving record of this book in the UK with only a handful of copies known elsewhere.

A cheap alternative

The simplest approach to making paste paper, like that used to wrap this 1791 essay on Marie-Antoinette, is to smear the coloured paste over two sheets of paper, stick them together and then pull them apart. This simple, cheap technique could be undertaken irrespective of skill or training and could produce vibrantly coloured and distinctive papers. Because of the relative ease with which they could be manufactured, paste papers were often made within the bookbinding workshop itself.

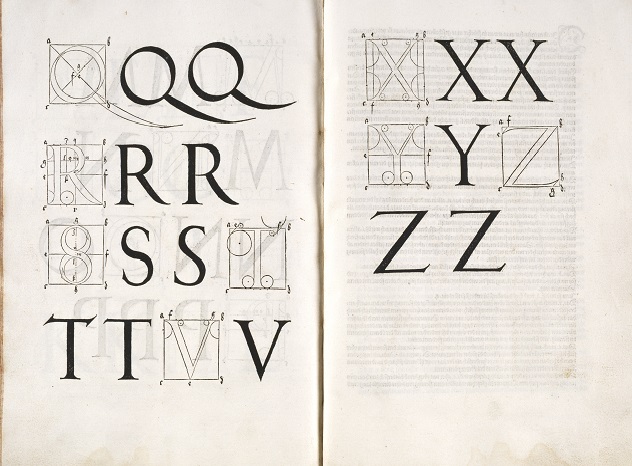

Woodblock printing

Printed by hand using a wooden block, this gilt paper is an early example of a trend for these repeating patterns found in decorated papers throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

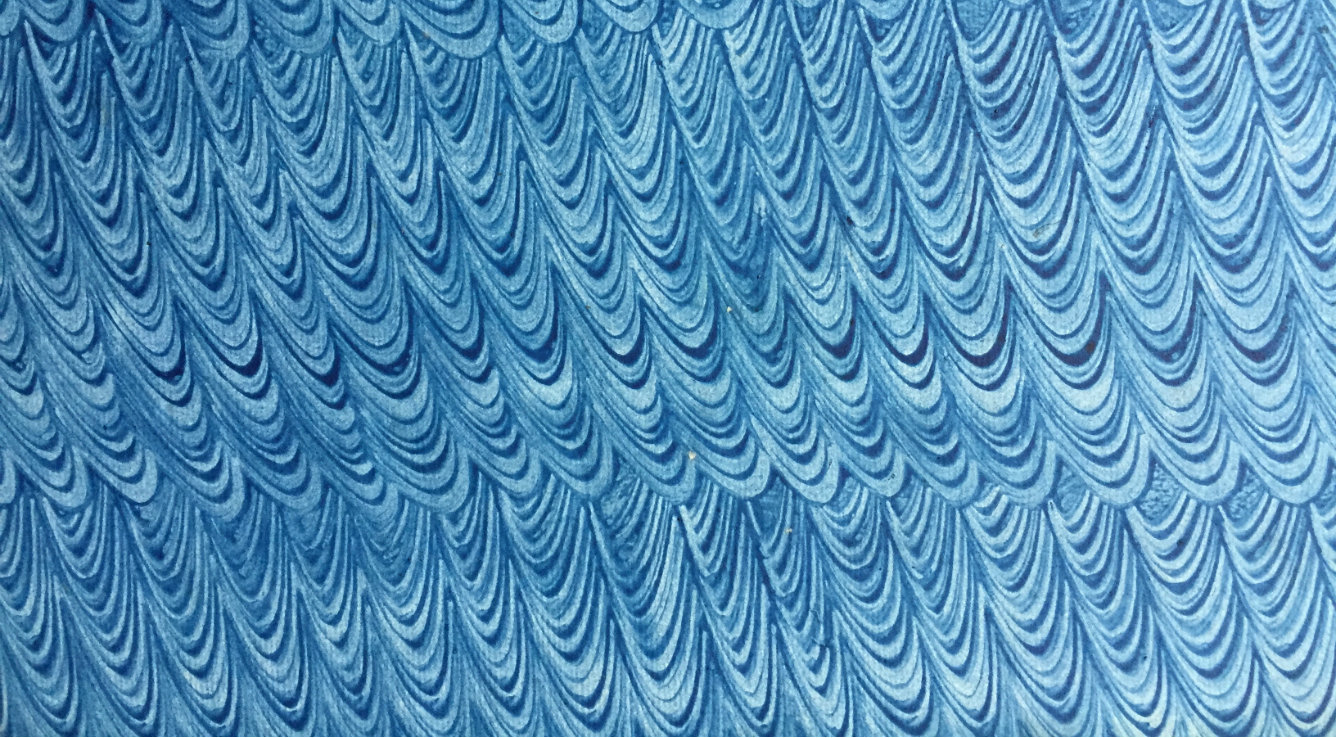

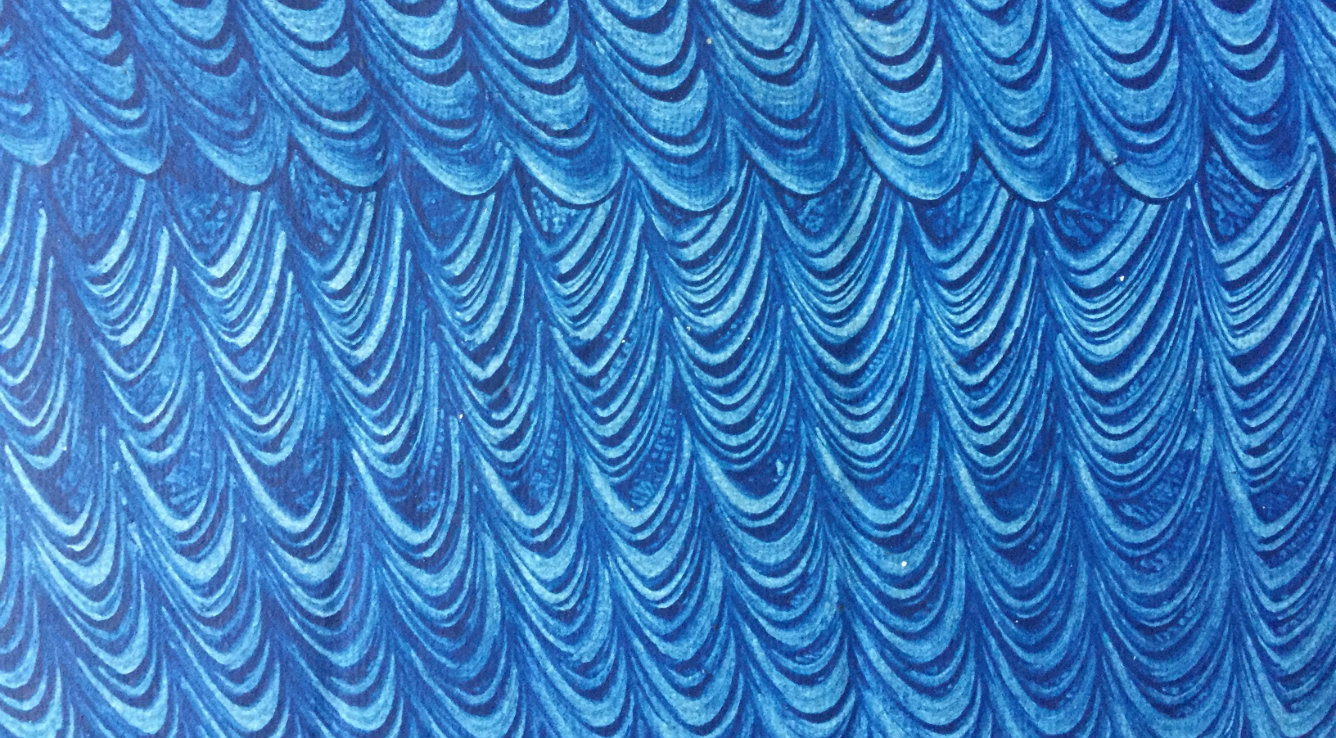

Dutch Curl

Old Dutch and Dutch Curl were very common patterns which dominated English binding for the first 75 years of the 18th century, before being superseded by patterns like French Shell and Stormont Antique Spot. Early binders are said to have reused marbled papers wrapped around imported toys, thereby avoiding the cost of paper duty.

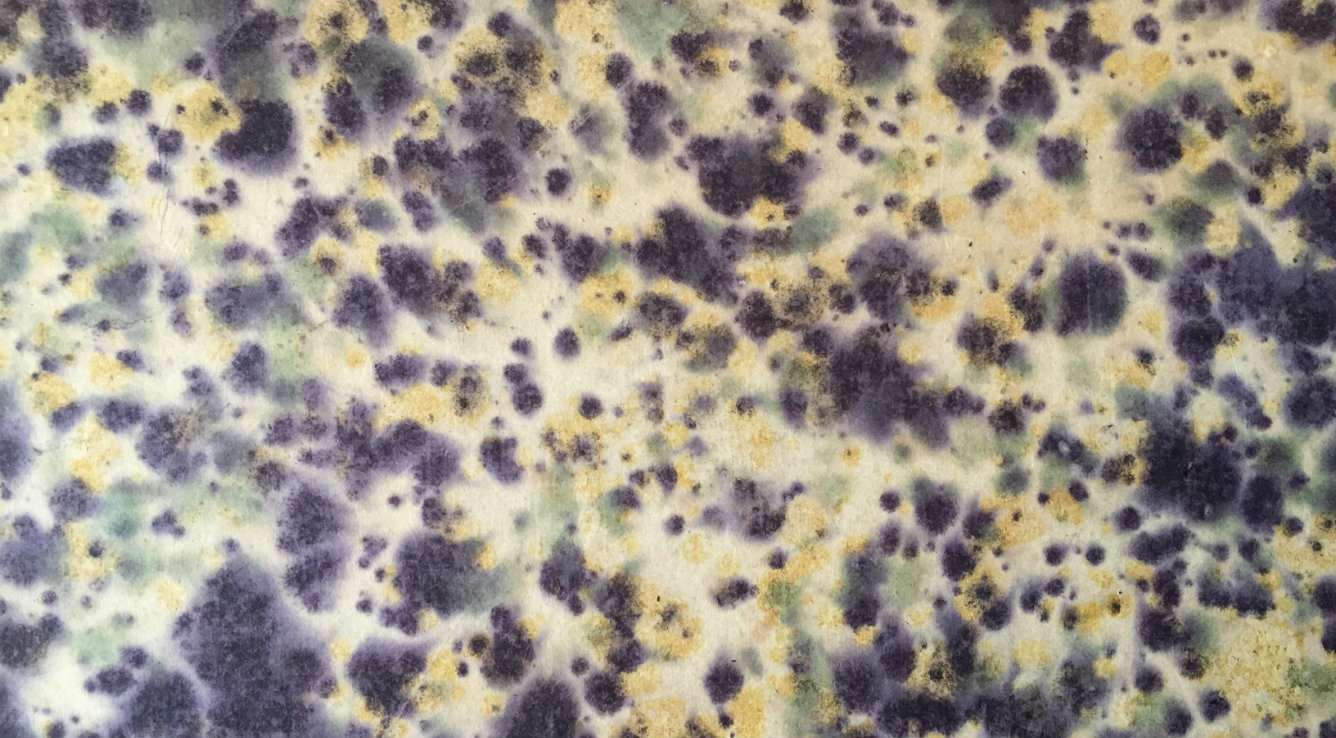

Sprinkled paper

This decorative Sprinkled paper must have been produced by sprinkling damp, absorbent paper with a coloured liquid or powder dye. The mould-like result is not to everyone’s taste, but is certainly distinctive, and proved popular throughout the 19th century.

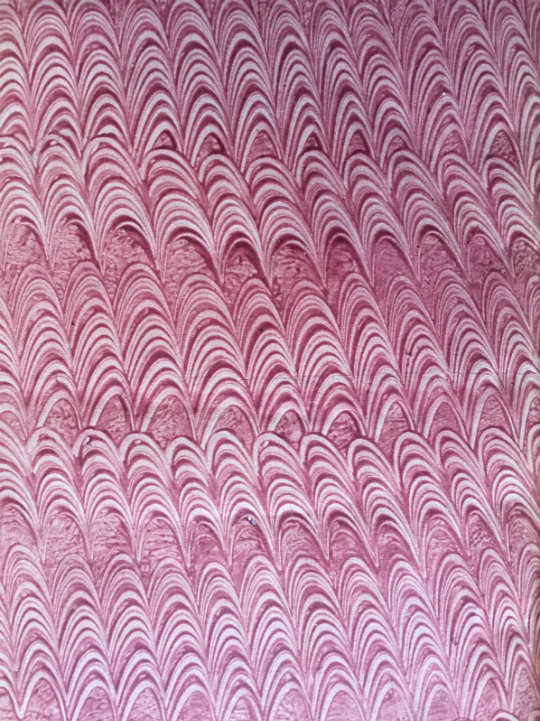

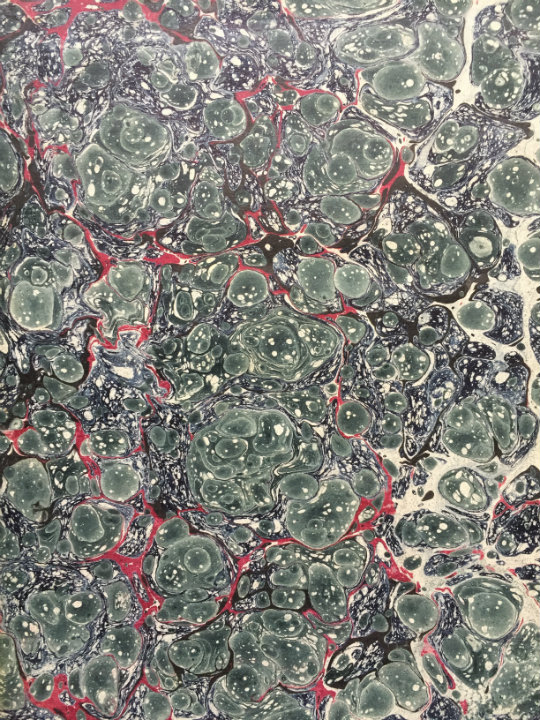

Shell Pattern marbled paper

In some instances, decorative papers were added to a book much later than the date of publication. John Strype's Life of Thomas Cranmer was published in 1695 and was bound soon after. The marbled paper was used to strengthen the hinges on the 150 year-old binding. It was acquired by Charles Winn (1795-1874), who amassed a vast and remarkable library at Nostell.

The style of the paper is characteristic of the period – a shell pattern where oil is added to the paint making up the spots, producing the graduated colour effect within them.

Combed marbled paper

In the 19th century marbled paper designs became more adventurous and elaborate, occasionally at the expense of beauty.

The 1874 edition of Gray’s poems was a favourite Eton prize book, and a number of copies share the use of this busy, combed marbled paper for flyleaves.

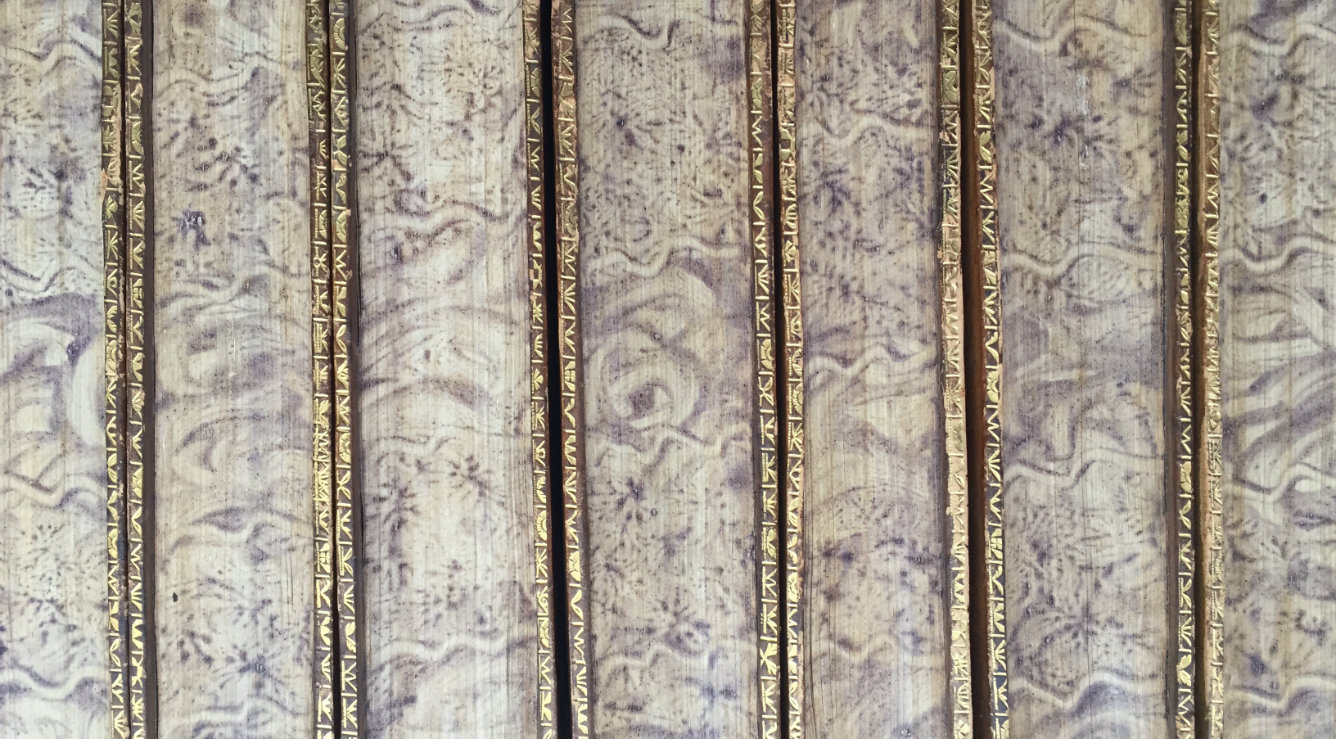

Paste-decorated edges

The techniques of paper decoration were adopted by bookbinders in all sorts of ways, not least to decorate the edges of books. The gilding of edges was practiced in England as early as the 1530s, and by the end of the 17th century some binders had taken to marbling the edges of cheap books. The widespread use of edge marbling took off in England at the same time as the use of marbled papers – the 1730s. By the end of the century it was de rigeur.

In this eight-volume set of David Hume's History of England, the binder adopted a different approach, one common in German books – using a coloured paste to give the edges a distinctive pattern.

Unconventional uses

Decorated papers were occasionally used in unexpected ways. Here, Dutch marbled paper was used to line the sliding trays in the mahogany clothes press made by Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779) for Sir Rowland Winn in 1767. Similar drawer linings can be found in several of Chippendale’s pieces at Nostell, but it appears to be a technique used only briefly. The Nostell commission is the only known example of Chippendale using marbled papers in this way.

Studying paper

The study of paper is more than just an aesthetic exercise. Decorated papers are beautiful, but they can also be used as a tool for dating, grouping and localising books.

The production of paper has been intimately intertwined with the production of books since the arrival of papermaking technology into Western Europe in the 11th century. The watermarks found in early paper have helped us to date otherwise undated documents, books and records of the trade in, and production of, paper. They have also allowed us to contextualise the spread of printing and books in the 15th and 16th centuries. Similarly, new research into fashions and tastes in the production and use of decorated papers are shaping our understanding of book use and trade from the 17th century to today. The library at Nostell Priory and the wider National Trust library collections offer rare opportunities to study how paper of all types was used in Western Europe over the last 500 years.

Sources

Beattie, Simon, Decorated Book Papers: a Beginner’s Guide, The New Antiquarian (The Blog of the Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America), 8 Feb 2018.

Gaskell, Phillip. A new introduction to bibliography, Winchester: St. Paul’s Bibliography, 1995.

Kopylof, Christiane. Papiers dorés d'Allemagne au siècle des Lumières: suivis de quelques autres papiers décorés, Bilderbogen, Kattunpapiere & Herrhutpapiere: 1680-1830; Paris: Aux Éditions des Cendres, 2012.

Middelton, Bernard. A history of English craft bookbinding technique, 4th ed, New Castle: Oak Knoll, 1996.

Schmoller, Tanya. A Yorkshire source of decorated paper in the eighteenth century, Sheffield: J. W. Northend Ltd., 2003.

Photographic credit

All photos, unless otherwise stated, are ©National Trust/Ed Potten.