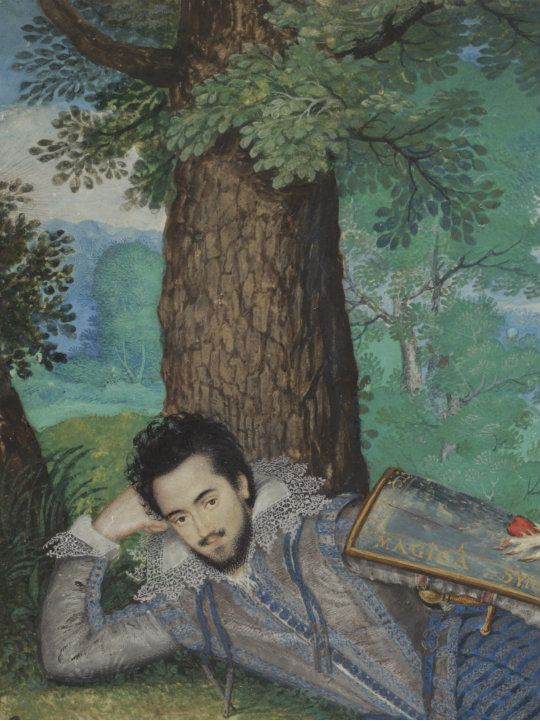

The dashing Sir Edward Herbert was as famous for his courtly accomplishments as he was for his courage in battle when he sat for this elaborate cabinet miniature in his early thirties (c.1613-1614).

Such full-length miniature likenesses, exquisitely rendered in bright pigments and precious metals, are exceptionally rare. Ever since it was first documented in 1764 this important commission has been attributed to Isaac Oliver, the official miniature painter of James I’s queen, Anne of Denmark. [1]

If his entertaining autobiography is anything to go by, we can be sure that Sir Edward (later 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury and Castle Island) took a special interest in how he was portrayed by the artist. [2] Like any self-respecting courtier, he was acutely aware of his image; totally out of the ordinary, however, was the personal testimony he left of his various portraits and the important people who possessed them. [3]

Particularly notable was Lady Ayres, a lady-in-waiting to the queen, who secretly commissioned from Oliver a miniature copy of a picture that now hangs at Charlecote Park. So enraged was this lady’s husband on finding this item (which hung ‘about her neck soe lowe that she yet hid it under her brestes’) that he ambushed his supposed rival with a dagger near Whitehall Palace in London and pierced his side! [4]

As well as being a soldier, philosopher, musician and, later in life, a diplomat, Sir Edward was a noted metaphysical poet whom even his friend, John Donne, envied for his ‘obscurenesse’. [5] It is easy to picture him setting out the complex imagery of his cabinet miniature with the same ingenuity with which he composed his elaborate verses, resulting in a work of art full of enigmatic symbols and witty messages, known at the time as conceits. However inviting these are to interpretation, some of their meanings remain tantalisingly ‘obscure’ even to this day.

Vita activa / vita contemplativa

The cabinet miniature cleverly plays out a debate in Renaissance ethics between the merits of two contrasting ways of life: a secluded existence spent in pursuit of the arts, philosophical meditation and private devotion (in Latin, the vita contemplativa) as opposed to a public life of military and political service (the vita activa). Sir Edward is poised between both spheres, showing off the virtues of both.

High on a tranquil wooded hilltop, he reclines beside a clear stream as it bursts out of the ground. A spring was a symbol of poetical inspiration and is perhaps prominently featured here as an allusion to Sir Edward’s reputation at the time for lyric verses and lute songs. [6] With his head propped up thoughtfully on his hand, he adopts the classic pose of a melancholiac. [7] Understood as a disorder of the mind and body, melancholy was diagnosed by low spirits but it also enjoyed fashionable currency for its other associations with creativity and deep philosophical meditation.

Beyond this contemplative retreat, the great world of action awaits. In the background, Sir Edward’s richly caparisoned horse paws impatiently at the ground while his squire prepares his armour for a joust. Staged by the monarch to celebrate state occasions, jousting contests were opportunities for knights to demonstrate their loyalty to the crown and martial skills, not least mastery of the powerful cavalry horses that were used both in the tiltyard and in real warfare. For ambitious courtiers like Sir Edward, the pageantry of jousting was deeply political. [8] These were opportunities to take centre stage before the king, his court and large crowds of ordinary people, and to parade chivalric qualities of honour and valour that qualified them for positions of power.

The navigable river that winds into the far distance at the top of the painting is also redolent of Sir Edward’s activities in the wider world. Conversant in French, Italian, Spanish, Ancient Greek and Latin, his thorough education had prepared him to take his place as a ‘Citizen of the world’. [9] Curiosity and a desire to refine his accomplishments had already led him to travel extensively in France where he had made himself popular at the royal court and been befriended by powerful nobles and scholars.

Sir Edward had also distinguished himself abroad as a soldier. A poem by Donne celebrates his friend’s prominent part in liberating the German city of Jülich from Hapsburg occupation in 1610, where he had joined a voluntary English expedition in support of an alliance of Protestant forces. [10]

The inspiration of Hilliard

The dynamic between action and contemplation in the picture was achieved by combining two models of cabinet miniature that Oliver’s teacher, Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547-1619), had invented late in the previous century. [11] If the composition is compared to the kinds of commissions this master completed some two decades earlier, its synthesis of earlier pictorial types becomes easy to see.

A direct counterpart to Sir Edward’s pensive pose and leafy seclusion can be found in Hilliard’s portrait of the 9th Earl of Northumberland with whom he shared (in quite different circles) a love of philosophical speculation. The undone collars of both men reveal the dishevelment of the melancholy man, but whereas Northumberland is attired in an unembellished and sombre black suit, Sir Edward appears in the eye-catching apparel of a young courtier.

Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland in contemplative seclusion by Nicholas Hilliard, 1590 - 1595

© Rijksmuseum

Sir Edward’s head-in-hand pose, like the Earl of Northumberland’s, indicates his melancholia

In this respect it evokes instead a dazzling jewel-like series of late Elizabethan miniatures of noblemen fitted up for the royal tiltyard. Hilliard’s portrait of the Earl of Cumberland in this vein shows Elizabeth I’s champion ready to spring into action. With one hand on his lance and other point poised manfully on his hip, all that remains for him to do is put the finishing touches to his armour, mount his steed and take to the lists.

By combining these pictorial antecedents, the miniature evokes two contrasting models of nobility but it also creates an innovative narrative dimension. It is as if Sir Edward is about to rise from the ground, lace up his collar ribbons and assume a more dynamic pose in the armour being prepared for him; one kind of portrait on the verge of transforming into another.

The 'impresa' shield

One of the most eye-catching details of the picture is the ornate shield looped round Sir Edward’s arm. Typical of shields used for jousting, it is carefully decorated with a combination of words (the motto) and an image (the device) known as an impresa. His motto, emblazoned in real gold around the border is MAGICA SYMPATHIAE, which is Latin for ‘the magic of sympathy’. The device is a heart borne aloft by sparking flames, the vivid redness of which glows out brilliantly against the cool blues and greens of the picture.

The 'impresa' shield with Sir Edward's motto, MAGICA SYMPATHIAE, emblazoned in real gold around the border

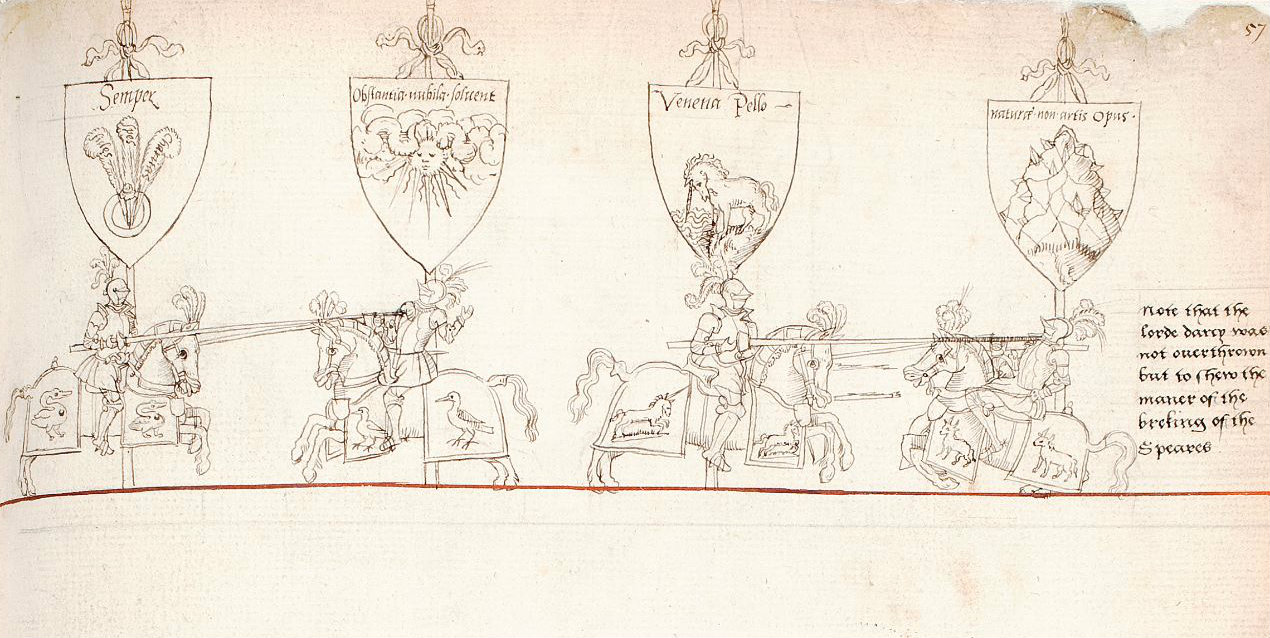

Unlike the family coats-of-arms which they sometimes resembled, imprese were designed to express some personal quality or ideal of their bearer, or send a message about their current position or desires for the future. [12] When jousting contests took place at Whitehall Palace, papier-mâché replicas of impresa shields were ceremonially presented to the monarch and hung in a special gallery.

Four early Elizabethan knights engaged in a joust. The drawing incorporates the designs of their 'impresa' shields.

The College of Arms, Ms. M. 6, Fol. 57a

Since these objects were integral to the highly public performance of royal jousting, professional writers of the calibre of William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson were sometimes employed to compose imprese. [13] For a scholar and poet like Sir Edward, however, these presented a valuable opportunity to demonstrate his own erudition.

Imprese were teasingly obscure, challenging their sophisticated observers to use their knowledge of courtly affairs, foreign languages, symbols and visual puns to decipher their meaning. In the words of the Elizabethan man-of-letters George Puttenham, they commonly contained,

two or three words of wittie sentence or secrete conceit till they [be] vnfolded or explained by some interpretation. For which cause they be commonly accompanied with a figure or portraict of ocular representation, the words so aptly corresponding to the subtilitie of the figure that aswel the eye is therewith recreated as the eare or the mind. [14]

In jousting tournaments, this moment of revelatory ‘interpretation’ arrived when a competitor rode into the lists and presented themselves to the monarch. A speech or dialogue was then recited by his squire or a retinue of costumed characters that explained the ‘secrete’ connection between motto and device, thereby revealing the knight’s intention.

Magica sympathiae

The theory of ‘the magic of sympathy’ was foundational to the philosophical writings of Sir Edward, notably his book De Veritate (‘On Truth’). [15] This was not published until 1624 although his use of the concept as a knightly ‘wittie sentence’ shows it was already a matter of consequence to him. [16]

From Renaissance mystical interpretations of ancient Greek thought had emerged a vision of the world wherein superficial or obscure ‘sympathies’ (resemblances and affinities) between distinct entities were actually glimpses of numberless profound connections that structured creation. [17]

Magic was the practice of using special signs and symbols to manipulate these universal threads of ‘sympathy’ to specific ends. Although he owned several books on the occult, Sir Edward seems to have had little time for the introverted magic of alchemy which most famously sought to turn worthless matter into gold. Instead, he set out to prove that humankind was capable of discerning the objective truth of concepts like the existence of God and the essential connections between the world’s religions. This was possible because in this ‘sympathetic’ universe, the body was a microcosm of all creation and the mind had a corresponding, inbuilt faculty for perceiving every possible object and idea.

One of the main truths with which De Veritate is concerned is the immortality of the human soul, to the extent that it has been suggested that the book ‘could be called a celebration of the soul’s immortality as an exposition of truth.’ [18] This could be relevant to Sir Edward’s device because a heart in flames was sometimes used as a symbol of the incorruptibility of the soul in the celestial realm. For that reason, the personification of Heaven in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (a favourite source of motifs for Jacobean court entertainments) holds in his hand an urn above which floats an inflamed heart. [19]

A pledge of loyalty

Sir Edward is not among the tiny number of combatants for whose impresa an explanatory speech or dialogue has survived. The kinds of messages that these extant texts convey, however, suggests the ingenious way in which the themes of his portrait, as well as his motto and device, might have been knitted together into a single statement of intention.

More often than not, these messages came down to an expression of loyalty and a pledge of service to the monarch, unsurprisingly in the context of royal pageantry. The elaborate presentation of the Earl of Essex composed by Francis Bacon at the 1595 Accession Day tournament is a particularly well-documented example. [20]

That year, Essex cantered into the Whitehall tiltyard adorned in the red and white livery of Love. There he encountered three characters personifying Self-Love: a power-hungry politician, a soldier thirsty for glory and a solitude-loving hermit. Having espoused the cause of these contrasting but equally selfish dimensions of the vita contemplativa and vita activa, the trio’s argument was eventually overruled through elaborate and flattering rhetoric. The competition between the different forms of self-indulgence was shown to be no competition at all when both action and contemplation were aligned in adoring service of the crown.

Given this kind of precedent, it is not difficult to see how ‘the magic of sympathy’ might have been used by Sir Edward as a metaphorical flourish to express similar fealty. If we acknowledge the monarch as the primary audience of a contestant decked out for the joust, a ‘secrete conceit’ can be imagined that ‘by some interpretation’ reconciled the active and contemplative personas depicted in the portrait into the single image of a loyal courtier. The obscure thread of ‘sympathy’ between the solitary man contemplating the mysteries of the universe and the warrior preparing to charge into the lists might therefore be construed as the virtuous instincts of a perfect knight.

... or a confession of love?

A further nuance could be brought to Sir Edward’s ‘secrete conceit’ by acknowledging the high importance attached to the gallant codes of courtly love by combatant knights. Though their primary audience was the monarch, facing the joust in honour of a virtuous court beauty was often part of the whole performance of chivalry. In the reign of Elizabeth I, the sovereign was inevitably the object of adoration although in other periods the queen consort or a mysterious lady-in-waiting might fulfil this role.

A knight’s ardour would be expressed by tying their mistress’s glove or scarf to their armour or by donning an appropriate impresa. One such example, which incorporated the device of a rose upon a branch of thorns, is known to have hung in the Whitehall Shield Gallery. Its frustrated motto was ABIGITQUE TRAHITQUE, Latin for ‘she both drives away and attracts.’ [21]

Like today, the heart on Sir Herbert’s shield was a symbol of love. Also like today, the sensation of romantic longing was described as burning with desire. In a poem written at around the same date as the miniature, Sir Edward used the ‘sympathetic’ concept of man as microcosm of the world to compare his hopeless tears of love to a pair of rivers. These he called upon to,

Ebb to my heart, and on the burning fires

Of my desires,

Let your torrents fall,

From smaller heat than their such sparks arise

As into flame converting all,

This world might be but my love’s sacrifice. [22]

The meaning of the heart amidst flames thus sits ambiguously between the immortal soul in heaven and the consuming fires of earthly passion. [23] Intriguingly, another love poem from this period demonstrates how Sir Edward was able to resolve this paradox with cunning rhetoric. In ‘An Ode upon a Question moved, Whether Love should continue for ever?’, a lover, lying on the grass in a wood, consoles his mistress with an ardent rhapsody on the Neoplatonic theory that true love on earth is an expression of a unique connection (or ‘sympathy’) between immortal souls that will transcend death and persist eternally in the heavenly sphere. [24]

The identification of Sir Edward as a courtly lover in his portrait helps to explain why his pose is so lilting, his expression so seductive. It is worth bearing in mind, after all, that melancholy was also an affliction of the love-stricken. [25]

The character of a passionate lover was certainly one that young gentlemen like Sir Edward were keen to adopt in their miniature likenesses. In a small oval miniature by Oliver at Ham House, an unidentified man appears as the star of his own impresa. Peering out from an inferno, above his head is inscribed the Latin motto ALGET QUI NON ARDET. This means ‘he becomes cold who does not burn’, suggesting that he will love his mistress until he dies.

A ‘conceit’ forever ‘secrete’

A profound philosopher; a man-at-arms; a heartthrob burning with desire; each of the aristocratic guises in which Sir Edward presents himself in his cabinet miniature adds nuance to the interpretation of its complex imagery. Its full and final intention, however, remains enigmatic.

But that, in a sense, is precisely the point. A teasing mysteriousness was all part of the fun of a courtly impresa but it was also a powerful instrument of social inclusion and exclusion, dividing the audience for tournaments according to rank and education. As one influential guide to composing these ‘conceits’ stipulated, an impresa should ‘not be so obscure that the divination of an oracle is needed to interpret its meaning, nor so transparent that every plebeian can understand.’ [26] In the absence of a surviving tiltyard speech or dialogue to explain Sir Edward’s impresa definitively, the historical record places the modern viewer decisively among the mass of ‘plebeian’ outsiders.

But all may not be entirely lost. It is worth making the obvious point that Sir Edward does not actually appear to us here in the socially stratified world of a real-life tiltyard, where the meaning of an impresa was ceremonially revealed, but in the highly artificial world of a cabinet miniature where no such convention is known.

The Green Closet at Ham House in Surrey is a unique surviving example of an early 17th-century English ‘cabinet’ gallery where small and precious works of art like Sir Edward’s portrait were viewed by the privileged few

©National Trust Images/John Hammond

In the kind of intimate gallery – ‘cabinet’ or ‘closet’ – where such precious works of art were enjoyed, a whole range of ingenious interpretations could have been devised out of the portrait’s symbols, concepts and themes by its erudite viewers. [27] In the literary circles in which Sir Edward moved as the friend of Donne and Ben Jonson, and the elder brother of George Herbert, tournament imprese were certainly seen as ‘open game’ in precisely this way when severed from court ceremonial.

Only a year or two before the portrait was painted, for instance, Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna or A Garden of Heroical Deuices was published. Here new verses were appended to pre-existing imprese to fashion wise emblems of universal application out of the highly personal intentions of their original bearers. [28] Far from confounding interpretation when encountered out of their ceremonial context, a mysterious knightly impresa appears to have been regarded by the Jacobean wit as an invitation to invent.

In this realm of sparking intelligence, the shifting, open-ended play of meanings produced by the ‘secrete conceit’ of Sir Edward’s cabinet miniature might, after all, be interpreted as its truest intent.

Notes

[1] ‘Ia. Oliver pinx.’ is inscribed beneath the print engraved by Anthony Walker (1726-1765), a specialist in Old Master reproductions, as a frontispiece for Horace Walpole’s edition of Herbert’s autobiography; The Life of Edward Lord Herbert of Cherbury, Written by Himself, Horace Walpole (ed.), Strawberry Hill, 1764. The miniature passed down through the family and came to Powis Castle after the line of descent of the Herberts of Cherbury (later Chirbury) merged with that of their cousins, the Herberts of Powis, by marriage in the 18th century. The early provenance of the miniature may mirror that of the manuscript autobiography, which was discovered with ‘some books, pictures and other things’ at the family’s Lymore estate in 1737, as outlined in Walpole’s unpaginated introduction.

[2] As well as discussing real portraits in his autobiography, Sir Edward used imaginary portraiture as a literary conceit to explore ideas of beauty, death and immortality in his metaphysical poetry; see ‘To his mistress on her true Picture’, The Poems: English and Latin, of Edward Lord Herbert of Cherbury, G.C. Moore Smith (ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press: 1923, p.48-53.

[3] Two of the portraits Herbert refers to in his autobiography are now in National Trust Collections: NT 1180912 and NT 533855; see The Life of Edward, First Lord Herbert of Cherbury, Written by Himself, London: Oxford University Press, 1976, pp.38, 60, 61.

[4] Ibid. pp. 60-66.

[5] According to their mutual friend Ben Jonson, Donne composed an elaborate elegy on the death of Prince Henry, heir to James I, in order ‘to match Sir Ed: Herbert in obscurenesse’; The Complete English Poems of John Donne, C.A. Patrides (ed.), London: Dent, 1985, p.377, headnote.

[6] Herbert’s poetry was published posthumously by his son in 1665. For a scholarly edition, see Poems, 1923. His manuscript collection of lute music, composed by Herbert and others, is held at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, MU.MA.689.

[7] For a recent history of the visual codes of melancholy in early modern England incorporating a discussion of the cabinet miniature of Sir Edward as a ‘late’ compendium of melancholic conventions see Drew Daniel, The Melancholy Assemblage: Affect and Epistemology in the English Renaissance, New York: Fordham University Press, 2013, pp.34-91, especially 44-49.

[8] Alan Young, Tudor and Jacobean Tournaments, London: George Philip, 1987, provides a detailed overview of the Early Modern culture of jousting and its political significance.

[9] Life, 1976, p.17.

[10] ‘To Sir Edward Herbert, at Julyers’, The Complete English Poems of John Donne, C.A. Patrides (ed.), London: Dent, 1985, pp.271-2.

[11] It has been suggested that, despite the emergence of newer conventions of cabinet miniature in the Jacobean period, Herbert commissioned an image that deliberately harked back to Elizabethan portrait styles; Roy Strong, The English Renaissance Miniature, London: Thames and Hudson, 1983, p.184.

[12] Young, 1987, pp.123-43.

[13] Ibid. p.129.

[14] George Puttenham, ‘The Arte of English Poesie (1589)’, in G. Gregory Smith (ed.), Elizabethan Critical Essays, London: Oxford University Press, 1904, vol. II, p.106.

[15] Edward Herbert, De Veritate, translated by Merick H. Carré, Bristol: J.W. Arrowsmith, 1937.

[16] Daniel plays down the possibility of serious philosophical meanings in the picture, pointing to its antecedence to the publication of De Veritate although no account is taken of the complex metaphysics that inform his more serious poems and anticipate his later writings at this date. Daniel, 2013, pp. 44-9.

[17] This account of the context and content of Sir Edward’s philosophy of sympathetic magic is based on Ronald D. Bedford, The Defence of Truth: Herbert of Cherbury and the Seventeenth Century, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1979, pp.93-105.

[18] Ibid. p.111.

[19] Iconolgia di Cesare Ripa, Matteo Florimi, 1613, p.103. Iconologia was first published in 1593. For Ben Jonson’s use of Ripa’s iconography at Jacobean masques see Stephen Orgel, The Illusion of Power: Political Theater in the English Renaissance, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975, p.29. Strong also offered a philosophical reading of the inflamed heart. Noting the wing-like rendering of the flames, he suggested that it might refer to the soul striving for divine knowledge, citing an emblem that uses a sparking winged heart to deliver that message in a 1635 collection by George Withers; Strong,1983, p.184.

[20] For a political analysis of Essex’s performance at the 1595 Accession Day, see Paul E.J. Hammer, ‘Upstaging the Queen: the Earl of Essex, Francis Bacon and the Accession Day celebrations of 1595’, in The Politics of the Stuart Court Masque, David Bevington and Peter Holbrook (eds.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp.41-66.

[21] Alan Young, English Tournament Imprese, New York: AMS Press, 1988, p.40, no.5.

[22] This untitled poem was composed in Italy in 1614; Poems, 1923, p.26.

[23] In Ripa’s Iconologia the burning heart appears not only as an attribute of Heaven but also of Desire; Ripa, 1613, p.153.

[24] An extended analysis of this is provided by Cleanth Brooks, Historical Evidence and the Reading of Seventeenth-Century Poetry, Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1991, pp.79-92. Herbert incorporates the same idea in a poem dated May 1608: ‘Thus when our souls that must immortal be, / For our loves cannot dye, nor we, (unless / We dye not both together) shall be free / Unto their open and eternal peace.’ Poems, 1923, p.17.

[25] Daniel, 2013, 180-1.

[26] ‘[C]h’ella non sia oscura, di sorte, c‘habbia mistero della Sibilla per interprete a volerla intendere; ne tanto chiara, ch’ogni plebeo l’intenda’, Paolo Giovio, Dialogo dell’Imprese Militari et Amorose, Guglielmo Roviglio, 1559.

[27] A short history of the tradition of the cabinet gallery with examples drawn from the National Trust is provided by Alistair Laing, In Trust for the Nation: Paintings from National Trust Houses, National Trust, 1996, pp.155-7.

[28] Henry Peacham, Minerva Britanna Or A Garden Of Heroical Deuises, furnished, and adorned with Emblemes and Impresa's of sundry natures, Walter Dight, 1612.

Further Information

All photos, unless otherwise stated, are ©National Trust Images.